The Places in Between (32 page)

Read The Places in Between Online

Authors: Rory Stewart

In the early afternoon we left a narrow gorge, passed a hot spring that, like so many in Afghanistan, was only lukewarm, and emerged into the broad, level fields of the Bamiyan valley. As the day became hotter, Babur began to lunge for every strip of shade he could find to lie down in, and I had to keep dragging him to his feet.

At the edge of the valley, we were absorbed into a rolling line of donkey caravans going to the market. Two small boys in bright blue gum boots and sparkling prayer caps sat atop bundles of thorn-brush kindling piled on donkeys. Beside them walked a young cow, her dull hide loosely draped from sharp hip bones. The cow was a speculation: The family had bought her in a mountain bazaar three days earlier and thought they could double their money by selling her, but in the meantime they could not afford to feed her. A lone man on a mule, slowed from a fast trot, forced his way between the donkeys and cantered ahead of us down the valley road. Behind him were hard-faced men who carried nothing on their donkeys and had come to buy oil and salt.

We drew level with four donkeys ridden by women wearing faded sky blue burqas, pulled out of cupboards in honor of the trip to town. They had lifted the skirts of their burqas to ride and I could see a baby peering out from the folds of one woman's mauve, scarlet, and purple underclothes. Their men walked beside them, wielding Buzkashi whips. The donkeys jibbed from side to side, easily distracted, heading up slopes toward village houses and bumping into each other, so that the drivers were at a continual trot around their flanks, shoving and pushing them back onto the path. Old men and young women on the donkeys crashed into each other from different angles. One man on foot with an orange hat perched on his curly ginger hair, a dark face, and brown corduroy

shalwar kemis

was perpetually sprinting off to capture a donkey that wanted to carry his wife and baby into the neighboring fields.

The silk and Buddhist scriptures carried into Bamiyan thirteen hundred years before must have arrived amid similar billows of sand and screams of muleteers. Earlier travelers such as Babur or Marco Polo, who moved in long columns of horses and pack animals, must not have seen the landscape for the dust. I was grateful I generally traveled alone.

The caravans dispersed around the remnants of the bazaar, which was a new kind of ruin—not with solid walls and blackened rafters but with the craters and shattered silhouettes that mark an aerial bombardment. A pale brown sandstone cliff hundreds of feet high rose sheer from the northern edge of a valley broader and more fertile than any I had seen since Herat. Cut into the cliffs to my left were two niches, each two hundred feet tall, with rubble at their bases. For fourteen hundred years, two large Buddhas stood in the niches. But seven months before I reached them, the Taliban dynamited the figures. This valley of Bamiyan, at eight thousand feet, was once the western frontier of the Buddhist world.

Part Seven

The Wurduk [tribe of the Pashtun] are all agricultural. They are a quiet sober people.

—Mountstuart Elphinstone,

The Kingdom of Kaubul and Its Dependencies,

1815

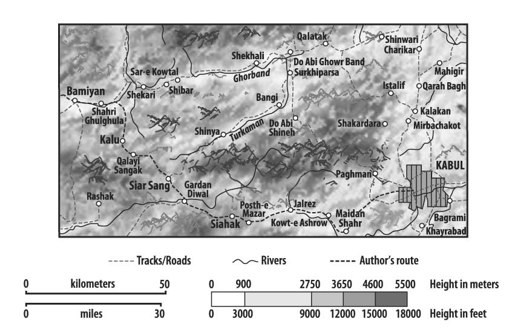

Days 30 & 31—Bamiyan

Day 32—Bamiyan to Kalu

Day 33—Kalu to Dahan-e-Siar Sang

Day 34—Dahan-e-Siar Sang to Siahak

Day 35—Siahak to Maidan Shahr

Day 36—Maidan Shahr to Kabul

FOOTPRINTS ON THE CEILING

Religions, like camel caravans, seem to avoid mountain passes. Buddhism spread quickly south from Buddha's birthplace in Nepal across the flat Gangetic plain to Sri Lanka. But it took a millennium to reach China and instead of crossing the Himalayas to get there it followed a parabolic curve one and a half thousand kilometers east, five hundred kilometers north, and two and a half thousand kilometers east again.

60

The religion eventually stretched to Mongolia and Japan, but in Afghanistan Buddhism filled only a narrow belt that left pagans in the valleys to the east and west in Kailash and in Ghor.

As Buddhism moved, it changed. In Tibet it incorporated the preceding Bon-Po religion and spawned new demonologies. In eighth-century northern India, it became scholastic; among the forest monks of Sri Lanka, pragmatic; in Newar, Nepal, married monks practiced inverted tantra; and in Japan, Zen devotees contemplated minimalist paradoxes. Afghanistan was where Buddhism met the art of Alexander's Greece. There, in the Gandharan style, it developed its most distinctive artistic expression: the portrayal of the Buddha in human form. The colossal statues of Bamiyan were the legacy of this innovation.

From the base of the eastern Buddha niche, I climbed forty feet up a sloping mud staircase, into a long, open corridor lined with empty rooms. I followed more steps upward. On either side the walls of the cliff were carved with balconies, circular staircases, and octagonal rooms with vaulted ceilings, rising story after story up the rock. I continued over fragile sections of mud, and emerged two hundred feet above the valley floor, where the head of the Buddha had once been.

This was distinctive mountain architecture. Afghanistan's Gandharan Buddhist sculpture is generally renowned for its grace and balance, but the Bamiyan Buddhas were ungainly and inflated. Their central function seems to have been to dominate the landscape. It was impossible to achieve detail or elegance of form in the loose crumbling rock. Everything had been sacrificed to allow the figures to climb up the face of the sandstone cliff.

Descending toward the other Buddha niche, I turned into a side passage, where I found a room still decorated with traces of dark blue and gold paint depicting figures in a procession. The last Bamiyan Buddhists probably lived at about the turn of the first millennium. Their religion, initially weakened by a Hindu revival, was extinguished by Islam. By the time the Ghorids captured the valley in the twelfth century, hardly a Buddhist was left between Bamiyan and Bangladesh. We know little about what kind of Buddhism was practiced in Bamiyan. From tens of thousands of monasteries stretched over a thousand kilometers, only fragments of stupas, sculpture, inscriptions, and manuscripts, and the records of Chinese travelers, remain.

At the end of another passage, I saw the Taliban had scorched the interior of a room, presumably to remove a fresco, and then stamped white boot prints over the ceiling. This must have taken some effort, as the ceiling was twenty feet high.

The Turquoise Mountain Ghorids, who chose this valley as their second capital, perhaps felt some affinity for this alternative mountain architecture and left the cliff Buddhas standing. The Taliban, however, had dynamited them out of disapproval of idolatry. Many Hazara seemed to have difficulty believing this. "Perhaps they were looking for gold underneath," suggested a man in the donkey caravan when I asked him. But they didn't seem worried about it. Finding the giant statues absent after they had been visible from every side of the valley for a millennium and a half must have been strange. But as the man said, "There are things that matter much more to us."

61

I sat down in a monk's meditation cell, set back from a long open veranda, and looked out over the broad green valley, a hundred feet below, to the white peaks beyond. The scene might once have resembled a miniature version of Lhasa before the Chinese invasion: the edifice around the Buddhas painted in bright colors, prayer flags on the peaks, and the valley filled on holy days by chanting processions of monks in saffron robes. The dynamited niches now echoed the earliest pre-Gandharan depictions, in which the Buddha is represented by an empty seat, showing where he had once been.

I AM THE ZOOM

Bamiyan was now a garrison town housing a major airstrip, foreign military personnel, and the offices of a number of relief agencies. The town was dominated by the new governor Khalili's soldiers—cleanshaven teenagers in camouflage jackets and new CIA-supplied combat boots, too large and unlaced. The tails of their double-breasted shirts hung to their ankles. Many of the boys had used black eyeliner to make themselves look beautiful. They filled the street, shouting at acquaintances, peering into shop fronts, fiddling with the Kalashnikovs on their backs, and interrogating strangers. Land Cruisers rolled past carrying aid agencies' personnel and American special forces. An Afghan commander's pickup stopped, a cold man holding the heavy machine gun mounted on its bed. No women were to be seen.

The northern passes were clear of snow and it was possible to drive to Kabul in eleven hours. A few vehicles were coming in every day. I wanted to find Babur transport to Kabul because he was too sick to walk the last hundred miles. I spent the afternoon in the bazaar talking to truck drivers but no one was prepared to take a dog. At dusk, I began to look for accommodation. Most travelers would have slept on the floor of one of the restaurants in the bazaar, but I was tired and didn't want to leave Babur in the street, so I resorted again to the international organizations. I tried not to bother MSF because I thought its staff had been generous enough in Yakawlang, but when none of the other agencies could take me in I fell back on MSF and was warmly welcomed.

I spent much of my two days' rest with a French photographer who was also staying in the MSF house. Didier Lefèvre had traveled across Afghanistan with the Mujahidin in the early 1980s, and he was back to photograph the war. Most war photographers carry large digital cameras; Didier was using black-and-white film and two old Leicas. In a war zone most photographers prefer to use a zoom. Didier didn't have one. "I am the zoom," he said. While other photographers were using cars and helicopters to chase news stories in different Afghan cities, Didier had been in Bamiyan for a month, photographing Hazara refugees. Didier was returning to Kabul in an MSF vehicle, and he and the driver kindly agreed to take Babur with them and drop him at a friend's house.

Taos of Bamiyan

KARAMAN

The next day I went to watch the Buzkashi game taking place on a series of fields—some fallow, some plowed and planted—just to the east of the empty Buddha niches. Buzkashi is a form of polo played with a dead goat instead of a ball. As I arrived, young grooms were walking their horses to limber them up while more horses cantered in through the dust, snorting into the cold air. White-bearded elders wearing suit jackets talked in low voices at the edge of the arena; and riders with turbans tightly tied beneath their chins strutted back and forth, tapping their whips nervously against their boots. No one was interested in talking to a foreigner.

This was one of the very first games since the Taliban had banned the sport. The crowd was discussing some of the men who had gathered to play: the feudal landlords Nasir and Shushuri, and Karaman, a famous player from Dang-e-Safilak in a tall woolen hat. Commandant Yawari from Yakawlang, it was said, had traveled three days on the mined road to be here on a horse valued at ten million Afghanis.

Some of the horses were village ponies with plain blankets, canvas girths, and reins made from string, but most were elaborately decorated. Abdul Qoudus from Shaidan was preparing his white stallion again. He had already dressed and undressed the animal twice. The horse was turning nervously on its halter and dribbling over its tight double bit. First Qoudus covered its back with the

julum

blanket he said had taken his wife a month to weave. It was a two-meter-long kilim with thirty bands of alternating black, white, and red designs, fringed with a line of quivering tassels. He laid a separate saddlecloth over the

julum

and tied a bright orange and green band, called a

taule,

around the horse's neck. He smoothed the tassels lying on the horse's nose and neck and flicked the glinting metal disks on the bridle to make them ring. He pulled a bright patchwork neck quilt with a diamond borderline and tassels over the horse's tall, blue-veined ears and stretched it to the horse's broad shoulders. In the center of the horse's forehead hung a brass disk set with green glass. Finally he lifted on the saddle, complete with high-rearing pommel. It was covered in burgundy carpet worked with black, orange, and white flowers and tassels of electric green and pink.