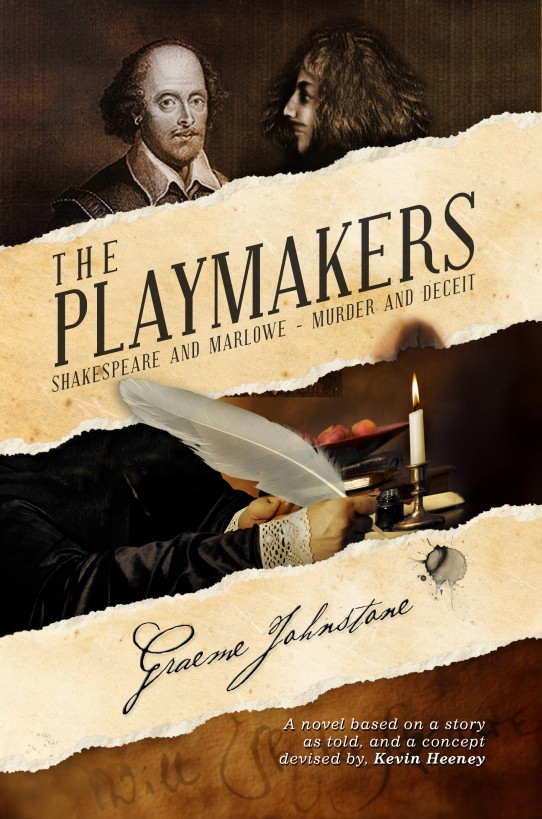

The Playmakers

Authors: Graeme Johnstone

Tags: #love, #murder, #passion, #shakespeare, #deceit, #torture, #marlowe, #plays, #authorship, #dupe

Shakespeare and Marlowe – murder

and deceit

Graeme Johnstone

A novel based on a story as told,

and a concept devised by, Kevin Heeney

The Playmakers

Shakespeare and Marlowe – murder and

deceit

Copyright © 2005, 2015 by Graeme Johnstone

G. & E. Johnstone

978-0-9925059-3-6

Smashwords Edition

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any

means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or

otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author.

The information, views, opinions and visuals

expressed in this publication are solely those of the author and do

not reflect those of the publisher. The publisher disclaims any

liabilities or responsibilities whatsoever for any damages, libel

or liabilities arising directly or indirectly from the contents of

this publication.

This book is a work of fiction. Any similarity

between the characters and situations within its pages and places

or persons, living or dead, is unintentional and coincidental.

1st Edition (2005)

BeWrite Books UK

ISBN 978-1-9052020-8-9

Dedicated to all those in the world who recognize

that not everything is what it seems.

THE PEOPLE BEHIND

THE PLAYMAKERS

1589

Execution was not their usual job. The two

men were normally messengers, occasionally spies, and, more often

than not, musclemen proficient at persuading a wavering soul to

support the Protestant ethic of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth.

Now, here they were, on a chilly April

evening - in front of a large, noisy mob of traders, smiths, wives,

layabouts, drunkards, thieves, rowdy low-lifers, and the Norwich

village comedian - struggling to set fire to a man chained to a

stake.

“Come on, get it going, we’re freezing over

here!” came a voice from the onlookers, inspiring a burst of

laughter.

One of the two appointed agents of the Court

of the Star Chamber, a bearded, beefy man with short bowlegs,

struggled up from the lifeless fire, intent on chastising the

unsighted heckler. His senior partner, taller, thinner and

clean-shaven, summoned him back to the task, throwing him a neatly

tied bundle of sticks.

“Just get these faggots in place,” the boss

hissed. “Strike the flint and let’s get it over and done with.”

“These faggots is green,” his deputy sullenly

replied, examining the bundle. He was right. Some of the twigs had

only recently been cut from the oak trees of the nearby forests in

Norfolk.

“Oh, I see, you’re going to let him freeze to

death, instead!” came the voice again.

Cavernous mouths containing blackened and

missing teeth opened in unison, and more laughter echoed through

the town square. The frivolity encouraged more observers to come

out of the shops to witness the burning of Francis Kett at the

stake.

The junior of the two executioners, his round

face flushed with anger, wiped his hands on a battered leather

waistcoat, which barely touched each side of his belly, and rose

again to snare the invisible miscreant. “Listen,” he shouted, “if I

catch whoever is saying that, he’ll be going up in flames along

with this bleedin’ atheist, all right?”

“At least I’d have a warm arse,” came the

mystery voice.

The crowd laughed again. But it was suddenly

stilled, not only by the executioner’s malevolent glare as he

waddled over to the faces in the front row, but a defiant burst of

sound from the person chained to the single wooden upright.

“I am not an atheist,” came the cry. “I am

not an atheist.”

It was the same phrase that Francis Kett,

poet, writer, visionary and Free Thinker, had shouted at the Star

Chamber hearing earlier in the day. He had screamed it in

frustration after hours of vainly presenting logical, intellectual

argument that his views on the earth, life, and the after-life were

not heretical. The bishops, sitting behind a high wooden table at

the end of the dimly lit room in Norwich Castle, had been

unmoved.

They did not brook thoughts that ran contrary

to the views of the Church of England. Thoughts that besmirched the

name of God. Thoughts that ran against all proper-thinking

Christian doctrine. Thoughts that could threaten their control

…

The guilty verdict had been a formality.

Francis Kett had repeated his protest as a

dozen hooded men had slowly marched him across the drawbridge out

of the castle where forty years before, another Kett, the wealthy

landowner Robert, had been beheaded for leading a rebellion against

social and religious change.

“I am not an atheist,” he had declared again,

as they passed through the unruly, jeering crowd and down the muddy

road to the centre of the east England village.

“What’s an atheist?” a poorly-clad pig

farmer, wiping his nose with the back of a grubby hand, had said to

a man standing next to him as the entourage walked by.

“An atheist? You don’t know what an atheist

is?” his friend said. “You’ve been spending too much time on them

pigs of yours.”

“Just tell me.”

“It means that he don’t believe in what you

and I believe in.”

“And what’s that, then?”

“You know, all things right and proper.”

“Right and proper, hey? That could mean

anything.”

“Exactly. It can, and does, mean anything

…”

And now, the crowd stood silent as the words

rang through the square.

“I am not an atheist!” Kett cried, his beard

wet with spittle, his dark hair matted, his once-sparkling brown

eyes dimming with resignation.

A cheery, well-rounded woman, her bonnet tied

tightly around puffy red cheeks, nudged a tall, skinny, redheaded

fellow next to her. “Go on, George, give them another!”

The tall man looked down, his blue eyes

sparkling from under a battered leather hat. He nodded, stroked his

ginger goatee for a second, cleared this throat and shouted, “Well,

mate, you may not be an atheist now, but you won’t be anything once

Gog and Magog can get this bleedin’ fire going!”

But on this occasion, the timing was wrong

and the joke fell flat.

Amid the awkward silence, the two bemused

executioners grabbed some drier wood, got down on their knees in

the stinking mud, and huffed and puffed the twigs into life. They

had chosen the method favoured by the Spanish and perfected through

the Inquisition – arranging the faggots so that they just reached

the victim’s waist. This gave the leering witnesses a clear view of

the offender writhing in agony, rather than dying behind a barrier

of flame from wood stacked too high.

The flames first danced around Kett’s legs,

setting fire to his breeches and singeing the skin, giving him a

terrible preview of what was to come. As they roared into life,

under stimulation from a small pair of bellows borrowed from a

nearby blacksmith, only Kett’s strong will and defiant intellect

enabled him to block out the excruciating pain and hold back from

screaming – the very response the crowd had come along to hear.

Nevertheless, the mob roared in glee as the

flames finally start to lick around his upper body, setting fire to

his shirt, forcing him to throw his head from side to side in

anguish.

Their joy was not shared by two men standing

at the back, their clothes and demeanour setting them apart from

the crowd.

On one, an undernourished, wispy fuzz

purporting to be a beard clung tenuously to the outer edges of an

almost perfectly oval face. A similarly reedy moustache battled for

credence against the authority of two handsome eyebrows and a

wonderful shock of brown hair drawn back from an expansive

forehead. The symmetrical curve of the sallow face was complemented

by two almond-shape brown eyes. Sharp eyes. Quick eyes. The eyes of

an observer.

On the other, the hazel eyes had an edge

about them, an element of alarm, an indication that the owner was

not comfortable yet with his life and his role. He was slightly

shorter than his companion, clean-shaven, with sandy hair and paler

skin.

Amid the crowd wearing crudely-cut leather

trousers and rough shirts, the pair stood out with their tailored

breeches, calf-high leather boots, capes, rakish hats with

feathers, and colourful doublets over spotless silk shirts.

The shorter of the two men, Thomas Kyd, spoke

first. “Why are we here? There is no comfort to be had watching a

friend burn at the stake.”

The man with the oval face, Christopher

Marlowe, replied, “But there may be some small comfort for him to

know that there are people here who believe in what he said.”

It was not uncommon for the well-educated

pair of young men to talk about death. They were both writers, with

Kyd working on a play,

The Spanish

Tragedy

, in which practically every character meets his

demise. An intense young man, Kyd saw this work-in-progress as his

big opportunity to break from the humdrum of academia and teaching,

and establish himself as a writer.

Cambridge-educated Marlowe, on the other

hand, had stolen a march on his friend, and was already becoming

the darling of the theatre set. His first play had been performed,

a masterpiece about the doomed Dr Faustus, and he was riding high

on the triumph.

But the deadly scene before them was no

fiction scrawled in longhand on a piece of scrappy parchment. This

was the real thing.

The pair fell silent again, watching as the

cruel flames began to sear Francis Kett’s flesh so badly it was

beginning to melt. Eventually he could hold out no longer and let

out an agonized bray. Such was its loudness, so sorrowful did it

sound, that it momentarily stilled the bubbling noise of the

crowd.

There was an eerie fragment of silence, and

then they burst into more shouts of glee.

“My God,” whispered Kyd, as tears welled,

“these animals think it’s fun.”

“Did you say God? Is there a God?” answered

Marlowe, as the eyes of their friend began to bulge from their

sockets and the flesh of his face drained into the flames. “How

could you even remotely consider there is a God, a God who would

allow such a monstrous thing to happen? Is death a deserved

punishment for letting the mind wander into fresh fields of thought

that others are so ignorant or so scared to even consider

entering?”

“Especially death like this,” said Kyd

angrily, “when the men who organise such a disgrace say they are of

the cloth and …”

Kyd stopped mid-sentence as he felt the force

of Marlowe’s right elbow into his left ribcage. He was about to

protest at the rough handling when he saw Marlowe cock his head to

a point in space behind Kyd’s right shoulder. “Shhh …”

Standing behind them and to the right was a

man looking fixedly at the grotesque scene, apparently oblivious of

their discussion. Marlowe had seen this face before. And he knew

this man was straining to hear every scrap of their talk over the

roar of the crowd.

Richard Baines was not the sort of person you

would want gleaning the slightest syllable of your conversation.

His weasel face and whippet-like frame matched his role in life as

an informer, the ultimate ferret of information for the Court of

the Star Chamber – some of it true, most of it not. He thrived in

these times of deep suspicion and organised spying, often being

seen in dark recesses of the Court, relaying in his familiar hoarse

whisper venomous reportage of yet another alleged indiscretion.