The Pleasure of My Company (6 page)

Read The Pleasure of My Company Online

Authors: Steve Martin

I stood

on the sidewalk facing the street with Kinko’s directly opposite me. The Land

Cruiser was on my right, so I hung to the left side of the driveway. There was

no way to justify the presence of that bumper. No, if I crossed a driveway

while a foreign object

jutted into it, I would be

committing a violation of logic. But, simultaneously driven forward and

backward, I angled the Land Cruiser out of my peripheral vision and made it to

the curb. Alas. My foot stepped toward the street, but I couldn’t quite put it

down. Was that a pain I felt in my left arm? My hands became cold and moist,

and my heart squeezed like a fist. I just couldn’t dismiss the presence of that

fender. My toe touched the asphalt for support, which was an unfortunate manoeuvre

because I was now standing with my left foot fully flat in the driveway and my

right foot on point in the street. With my heart rapidly accelerating and my

brain aware of impending death, my saliva was drying out so rapidly that I

couldn’t remove my tongue from the roof of my mouth. But I did not scream out.

Why? For propriety. Inside me the fires of hell were churning and stirring; but

outwardly I was as still as a Rodin.

I

pulled my foot back to safety. But I had leaned too far out; my toes were at

the edge of the driveway and my body was tilting over my gravitational centre.

In other words, I was about to fall into the street. I windmilled both of my

arms in giant circles hoping for some reverse thrust, and there was a moment,

eons long, when all 180 pounds of me were balanced on the head of a pin while

my arms spun backward at tornado speed. But then an angel must have breathed on

me, because I felt an infinitesimal nudge, which caused me to rock back on my

heels, and I was able to step back onto the sidewalk. I looked across the

street to Kinko’s, where it sparkled in the sun like Shangri-la, but I was separated

from it by a treacherous abyss. Kinko’s would have to wait, but the terror

would not leave. I decided to head toward home where I could make a magic

square.

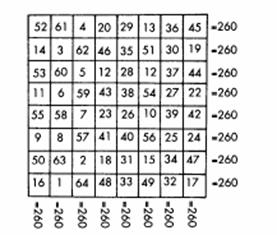

Making

a magic square would alphabetize my brain. “Alphabetize” is my slang for “alpha-beta-ize,”

meaning, raise my alphas and lower my betas. Staring into a square that has

been divided into 256 smaller squares, all empty, all needing unique numbers,

numbers that will produce the identical sum whether they’re read vertically or

horizontally, focuses the mind. During moments of crisis, I’ve created magic

squares composed of sixteen, forty-nine, even sixty-four boxes, and never once

has it failed to level me out. Here’s last year’s, after two seventy-five-watt

bulbs blew out on a Sunday and I had no replacements:

Each

column and row adds up to 260. But this is a lousy 8 X 8 square. Making a 16 X

16 square would soothe even the edgiest neurotic. Benjamin Franklin—who as far

as I know was not an edgy neurotic—was a magic square enthusiast. I assume he

tackled them when he was not preoccupied with boffing a Parisian beauty, a

distraction I do not have. His most famous square was a king-size brainteaser

that did not sum correctly at the diagonals, unless the diagonals were bent

like boomerangs. Now that’s flair, plus he dodged electrocution by kite.

Albrecht Dürer played with them too, which is good enough for me.

I

pulled my leaden feet to the art supply store and purchased a

three-foot-by-three-foot white poster board. If I was going to make a 256-box square,

I wanted it to be big enough so I didn’t have to write the numbers

microscopically. I was, after the Kinko’s incident, walking in a self-imposed

narrow corridor of behavioural possibilities, meaning there were very few moves

I could make or thoughts I could think that weren’t verboten. So the purchase

didn’t go well. I required myself to keep both hands in my pockets. In order to

pay, I had to shove all ten fingers deep in my pants and flip cash onto the

counter with my hyperactive thumbs. I got a few impatient stares, too, and then

a little help was sympathetically offered from a well-dressed businessman who

plucked a few singles from the wadded-up bills that peeked out from my pockets

and gave them to the clerk. If this makes me sound helpless, I feel you should

know that I don’t enter this state very often and it is something I could snap

out of, it’s just that I don’t want to.

Once

home, I laid the poster board on my kitchen table and, with a Magic Marker and

T square, quickly outlined a box. I drew more lines, creating 256 empty spaces.

I then sat in front of it as though it were an altar and meditated on its

holiness. Fixing my eyes on row 1, column 1, a number appeared in my mind, the

number 47,800. I entered it into the square. I focused on another position.

Eventually I wrote a number in it: 30,831. As soon as I wrote 30,831, I felt my

anxiety lessen. Which makes sense: The intuiting of the second number

necessarily implied all the other numbers in the grid, numbers that were not

yet known to me but that existed somewhere in my mind. I felt like a lover who

knows there is someone out there for him, but it is someone he has not yet

met.

I

filled in a few other numbers, pausing to let the image of the square hover in

my black mental space. Its grids were like a skeleton through which I could

see the rest of the uncommitted mathematical universe. Occasionally a number

appeared in the imaginary square and I would write it down in the corresponding

space of my cardboard version. The making of the square gave me the feeling

that I was participating in the world, that the rational universe had given me

something that was mine and only mine, because you see, there are more possible

magic square solutions than there are nanoseconds since the Big Bang.

The

square was not so much created as transcribed. Hours later, when I wrote the

final number in the final box and every sum of every column and row totalled 491,384,

I noted that my earlier curbside collapse had been ameliorated. I had eased up

on my psychic accelerator, and now I wished I had someone to talk to. Philipa

maybe, even Brian (anagram for “brain”—ha!), who I now considered as my closest

link to normalcy. After all, when Brian ached over Philipa, he could still

climb two flights up and weep, repent, seduce her, or buy her something. But my

salvation, the making of the square, was so pointless; there was no person attached

to it, no person to shut me out or take me in. This healing was symptomatic

only, so I tacked the cardboard to a wall over Granny’s chair in the living

room in hopes that viewing it would

counter my next bout of

anxiety the way two aspirin counter a headache.

Clarissa

burst through the door clutching a stack of books and folders in front of her

as though she were ploughing through to the end zone. She wasn’t though; she

was just keeping her Tuesday appointment with me. She had brought me a few

things, probably donations from a charitable organization that likes to help

half-wits. A box of pens, which I could use, some cans of soup, and a soccer

ball. These offerings only added to my confusion about what Clarissa’s

relationship to me actually is. A real shrink wouldn’t give gifts, and a real

social worker wouldn’t shrink me. Clarissa does both. It could be, though, that

she’s not shrinking me at all, that she’s just asking me questions out of

concern, which would be highly unprofessional.

“How…

uh…” Clarissa stopped mid-sentence to regroup. She laid down her things. “How

have you been?” she finally asked, her standard opener.

I

couldn’t tell her about the only two things that had happened to me since last

Friday. You see, if I told her about my relationship with Elizabeth and of my

misadventures with Philipa, I would seem like a two-timer. I didn’t want to

tell her about Kinko’s, because why embarrass myself? But while I was trying to

come up with something I could tell her, I had this continuing tangential

thought: Clarissa is distracted. This is a woman who could talk non-stop, but

she was beginning to halt and stammer. I could only watch and wonder.

“Ohmigod,”

she said, “did you make this?” and she picked up some half-baked pun-intended

ceramic object from my so-called coffee table, and I said yes, even though it

had a factory stamp on the bottom and she knew I was lying, but I loved to

watch her accommodate me. Then she halted, threw the back of her hand to her

forehead, murmured several “uhs,” and got on the subject of her uncle who

collected ceramics, and I knew that Clarissa had forgotten that she was

supposed to ask me questions and I was supposed to talk. But here’s the next

thing I noticed. While she spun out this tale of her uncle, something was going

on in the street that took her attention. Her head turned, her words slowed and

lengthened, and her eyes followed something or someone moving at a walking

pace. The whole episode lasted just seconds and ended when she turned to me and

said, “Do you ever think you’d like to make more ceramics?”

Yipes.

Is that what she thinks of me? That I’m far gone enough to be put in a straitjacket

in front of a potter’s wheel where I can sculpt vases with my one free nose? I

have some image work to do, because if one person is thinking it then others

are, too.

By now

the view out the window had become more interesting, because what had so

transfixed Clarissa had wandered into my field of vision. I saw on the sidewalk

a woman with raven hair, probably in her early forties. She was bent down as

she walked, holding the hand of a one-year-old boy who toddled along beside her

like a starfish. I had looked out this window for years and knew its every traveller,

could cull tourists from locals, could discern guests from relatives, and I had

never seen this raven-haired woman nor this one-year-old child. But Clarissa

spotted them and was either curious or knew something about them that I didn’t

know.

Then

Clarissa broke the spell. “What’s this?” she asked.

“Oh,” I

said. “It’s a magic square.”

Clarissa

arched her body back while she studied my proudest 256 boxes.

“Every

column and row adds up to four hundred ninety-one thousand, three hundred

eighty-four,” I said.

“You

made this?”

“Last

night. Do you know Albrecht Dürer?” I asked. Clarissa nodded. I crouched down

to my bookshelf, crawling along the floor and reading the titles sideways. I

retrieved one of my few art books. (Most of my books are about barbed wire.

Barbed wire is a collectible where I come from. I admired these books once at

Granny’s house and she sent them to me after Granddaddy died.) My book on Dürer

was a real bargain-basement edition with colour plates so out of register they

looked like Dürer had painted with sludge. But it did have a reproduction of

his etching

Melancholy,

in which he incorporated a magic square. He even

worked in the numbers 15 and 14, which is the year the print was made, 1514. I

showed the etching to Clarissa and she seemed spellbound; she touched the page,

lightly moving her fingers across it as if she were reading Braille. While her

hand remained in place she raised her eyes to the wall where I had tacked up my

square. She then went to her Filofax and pulled Out a Palm Pilot, tapping in

the numbers, checking my math. I knew that magic squares were not to be

grasped with calculators; it is their mystery and symmetry that thrill. But I

didn’t say anything, choosing to let her remain in the mathematical world.

Satisfied that it all worked out, she stuck the instrument back into its

leatherette case and turned to me.

“Is

this something you do?” she said.

“Yes.”