The Pope and Mussolini (31 page)

Read The Pope and Mussolini Online

Authors: David I. Kertzer

Tags: #Religion, #Christianity, #History, #Europe, #Western, #Italy

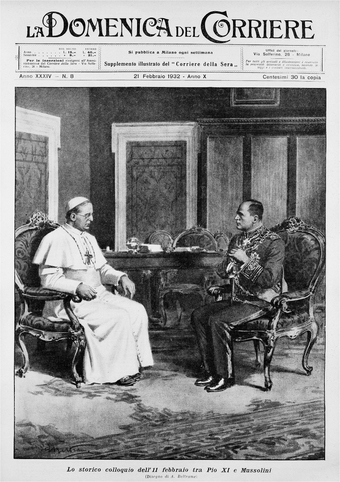

Mussolini and the pope, in the pope’s library, February 11, 1932

The historic meeting generated worldwide press coverage. “Pope and Duce Clasp Hands in Friendship Pact,” read the

Chicago Daily Tribune

headline. The front-page

New York Times

headline declared “Pope and Mussolini Show Warm Feeling in Vatican Meeting.”

8

But the best description we have of their encounter—the only time the two men would ever meet—comes from Mussolini himself, who wrote an account by hand to send to the king.

The pope invited him to sit, asking how his daughter, Edda, was doing in Shanghai, where her husband was serving as Italian consul.

After a minimum of such pleasantries, Pius brought up the subject he thought most pressing. Protestant proselytizing, he told a surprised Mussolini—who was not expecting this to be at the top of the agenda for the meeting—“is making progress in almost all of Italy’s dioceses, as shown in a study that I had the bishops do. The Protestants are becoming ever bolder, and they speak of ‘missions’ they want to organize in Italy.” They were taking advantage of the concordat’s unfortunate language, which referred to non-Catholic religions as “admitted” cults. The pope had opposed that phrase, preferring that they be described as “tolerated.”

Mussolini pointed out that only 135,000 Protestants lived in Italy, 37,000 of them foreigners—a mere speck amid 42 million Catholics.

The pope acknowledged that the Protestants were few but argued that the threat was nonetheless great. He handed the Duce a lengthy report on the question. Over the next years he would bombard the dictator with requests to keep the Protestants in check.

The conversation then turned to the recent conflict over Catholic Action, and here we must treat Mussolini’s account of the pope’s words with caution. After expressing his pleasure that the dispute had been settled amicably, the pope added—according to the Duce—“I do not see, in the complex of Fascist doctrines—which tend to affirm the principles of order, authority, and discipline—anything that is contrary to Catholic teachings.”

The pope added that he could understand the principle of “totalitarian fascism,” but this could refer only to the material realm. There were also spiritual needs, he said, and for these what was needed was “Catholic totalitarianism.”

“I agreed with the Holy Father’s opinion,” commented Mussolini. “State and Church operate on two different ‘planes’ and therefore—once their reciprocal spheres are delimited—they can collaborate together.”

Finally the pope expressed his distress at what was going on in Russia where, he said, the Bolsheviks were intent on destroying Christianity. “Beneath this,” said Pius, “there is also the anti-Christian loathing of Judaism.” When he was nuncio in Poland, he recalled, “I saw that in all the Bolshevik regiments the civilian commissars were Jews.” The pope thought Italy’s Jews an exception. He fondly told the Duce of a Jew in Milan who had made a major gift to the church, and of the help that Milan’s rabbi had given him in deciphering “certain nuances of the Hebrew language.”

At the end of the meeting, the pontiff presented the Duce with three more papal medals.

9

Mussolini then made his way to the secretary of state’s office, where he spent twenty minutes with Cardinal Pacelli. Then he was escorted down into St. Peter’s to kneel before the Altar of the Madonna. When newspaper photographers tried to take a photo of him in prayer, he abruptly got up and shooed them away. “No. No. When one is praying,” he said, “one should not be photographed.”

10

No one would photograph the dictator on his knees.

Mussolini arrived home in an ebullient mood. Eager to hear details of the visit, his children gathered around him. Rachele was less impressed, interrupting his glowing account by asking acidly: “Did you also kiss his feet?” On this note, his narration came to an abrupt end.

11

The next month, in an orgy of honorifics, Mussolini and the king reciprocated the honors. They bestowed on Cardinal Pacelli the Supreme Order of the Most Holy Annunciation—Italy’s highest decoration, making him a “cousin” of the king—and awarded the Grand Cross of Saints Maurice and Lazarus to Pacelli’s two undersecretaries of state, Monsignors Pizzardo and Ottaviani. But what most caught the attention of the clergy was the honor given to someone who had no official Vatican position at all: Father Pietro Tacchi Venturi, too, received a Grand Cross.

12

Mussolini at the Vatican following his meeting with the pope, February 11, 1932; from front left: Monsignor Caccia Dominioni, Cesare De Vecchi, Mussolini

The pope now settled into a period of collaboration with the Italian dictator. To the bishop of Nice, who happened to be in Rome, the pope explained that it was thanks to Mussolini that the Catholic Church once again occupied a powerful position in Italy. When the bishop reminded him of the recent bruising battle over Catholic Action, the pope blamed it on the anticlerics who surrounded Mussolini. “I can still see him,” said the pope, “sitting in the same seat where you are sitting, telling me, ‘I recognize that we made some mistakes, but I had to battle against my entire staff.’ ”

13

––

THAT SAME YEAR THE

pope celebrated his seventy-fifth birthday, triggering an outpouring of admiration in the world’s press. In a lengthy article,

The New York Times Magazine

gushed about the “surprising discovery” that behind the “quiet scholarliness of the Prefect of the Vatican Library were the traits of a born ruler of men.” (The

Times

portrait unknowingly echoed a comment Cesare De Vecchi had made after a meeting with the pope three years earlier: “Every other will gives way before that of the Holy Father,” he said, adding that he could easily imagine Pius XI at the head of a government or an army. “Every possible intrigue crumbles on contact with this block of granite.”)

14

Pius still had the vigorous step of a younger man, the

Times

article affirmed, and spent virtually all his waking hours at work.

15

The pope certainly kept a crushing schedule. During the 1933–34 Holy Year, two million pilgrims would come to Rome, and he met with many of them, making innumerable speeches and celebrating countless masses. Marking the nineteen hundredth anniversary of the crucifixion, the Holy Year ran from Easter to Easter.

16

Pius XI was no orator. At public audiences, he made up his remarks as he went along, delivering them in a slow staccato, pausing as he considered each new thought. He often spoke of “the House of the Father” or “the Common Father of the faithful.” Other times he took advantage of a saint’s day or seized on some characteristic—national or occupational—of the visiting group to develop his theme. He had a well-deserved reputation for long-windedness, and given the length of his speeches, the size of the crowds he drew, and the often-stifling heat, it was not unusual for someone in the audience to faint before he finished. During Lent in 1934 he lectured a group of preachers on the virtue of keeping sermons brief—speaking for forty-five minutes to make his point.

17

Cardinals of the Curia and other Vatican prelates continued to live in fear of him. The pope, observed the archbishop of Paris, would never admit to being wrong and had a habit of uttering pithy phrases

that he took to be unquestioned truths. Gaetano Bisleti, the venerable cardinal who had crowned Ratti with the papal tiara in 1922, prepared for his audiences by going to his favorite Vatican chapel, getting down on his knees on the marble floor, and praying that the pope would find no fault with what he had to say. Monsignor Alberto Mella, who following Caccia’s appointment as cardinal became master of ceremonies, prayed to all the saints in heaven before entering the pope’s study, hoping that the pope would not find him wanting. A number of cardinals, afraid to approach the pope and risk incurring his wrath, confided in Pacelli, hoping he would use his diplomatic skills to get the pope to do what they wanted.

18

But especially when dealing with laymen, the pope knew the value of a soft word. A visitor who entered the pope’s presence in the Apostolic Palace genuflected three times. Non-Catholics were supposed to bow as well as Catholics, but this did not come easily to some. One day a group of Protestants visited the pope. All dropped to one knee, except for one man who, ill at ease, remained defiantly—if a bit unsteadily—on his feet. The pope’s aides tensed, exchanging furtive glances to see who would deal with the problem. But while they dithered, the pope walked up to the holdout and asked, “Won’t you receive a simple old man’s blessing?” This was too much for the recalcitrant Protestant, and he too got down on bended knee.

19

In the tradition of European monarchs, the pope kept bags of money in his library drawers to dispense to deserving petitioners. Domenico Tardini, Pizzardo’s undersecretary in the Congregation for Extraordinary Ecclesiastical Affairs, was in charge of coordinating aid for Russian relief and often had to ask for funds. A short Roman prelate with a square face and thick dark woolly hair, Tardini was highly sensitive to the pope’s moods. “At nine with the pope, another hour of audience,” he wrote in his diary on April 9, 1934. “Today too he is in excellent spirit: the infallible thermometer measured by the size of his donations.” As Tardini detailed his request, the pope, his attention drifting, rearranged the gold coins he had extracted from his drawer, sorting them by size into neat piles atop his desk.

When he was in a good mood, the pope, not known for his sense of humor, was capable of a witty remark. Earlier that year he had urgently summoned the French ambassador to discuss something that was on his mind. Upon his arrival, the ambassador apologized for not wearing his usual formal dress. The pope smiled. “Yes, I know,” he said. “Ordinarily you come in leatherbound edition. Today you come as a paperback.”

20

Other times the pope was more irritable. “Today,” Tardini wrote on October 5, “the pope is readier than ever to contradict and oppose. It all depends on his mood, on some painful experience in the past, on … his bad digestion, I don’t know. But what is certain is that the pope is always ready to be suspicious and to do the exact opposite of whatever someone suggests he do.” Tardini, who knew him well, came up with a solution. When the pope was in a bad mood, he could be counted on to deny any request. So on such days, Tardini would propose the opposite of what he wanted and could be sure he would succeed, or so he claimed. “That’s what I did today,” wrote Tardini in his diary one day, “and with excellent results.”

21

Although working a punishing schedule, the pope did have his modest diversions. Loving order, he carefully kept every item in his desk in its proper place and wasted nothing. He even kept a neat pile of ribbons removed from packages he opened. The son of a textile factory manager, he took pleasure in little mechanical projects. For many years, he kept a tiny screwdriver in his desk so he could tinker with clocks. When a spray of oil or a drip of ink stained his white vest, he would, when he was sure no one was looking, do his best to scrub it off.

22

Now that he no longer had to cast himself as a “prisoner of the Vatican,” the pope could enjoy a new diversion. On July 10, 1933, in a carriage with blinds drawn, he left Rome for the first time, bound for the papal estate at Castel Gandolfo in the Alban Hills. The area’s cool, crisp air, famed wines, and natural beauty had drawn distinguished Romans since ancient times. The papal estate there had been unused since 1869. On his first visit, Pius XI inspected the repair work under way. The next year he began spending his summers there, two months

in 1934 and 1935 and longer periods later. Each day he spent at the summer palace, his assistants brought papers for him to review, and he held audiences. But his pace was much reduced. While strolling through the extensive gardens, the pope could glance down a hundred meters at the lake below, formed by the mouth of an extinct volcano. Breathing the fresh air and feeling closer to nature gave him great pleasure, bringing back memories of the small-town life he had left behind.

23