The Punishment of Virtue (3 page)

Read The Punishment of Virtue Online

Authors: Sarah Chayes

For that report, I had interviewed truck drivers who were transporting loads of Kandahar's trademark pomegranates across the border to merchants in Pakistan. Were those workingmen “pro-bin Laden?” A withering U.S. bombing campaign was under way. In that context, could not villagers be simply fleeing their homes under the rain of fire, without guilt by association with the Taliban? Andâa most difficult question for Americans to untangleâwas pro-Taliban necessarily the same as pro-Bin Laden?

These were the sorts of distinctions, I was learning, that it was imperative to make. Otherwise, we were going to get this wrong, with devastating consequences.

MOVING IN ON KANDAHAR

NOVEMBER 2001

Z

ABIT

A

KREM

(as he was called then, for the lieutenant's rank he had earned in military academy) was in Quetta the same time I wasâsometimes a few streets or a building away, no doubt. Those days, it seemed like the whole world was in Quetta, Pakistan.

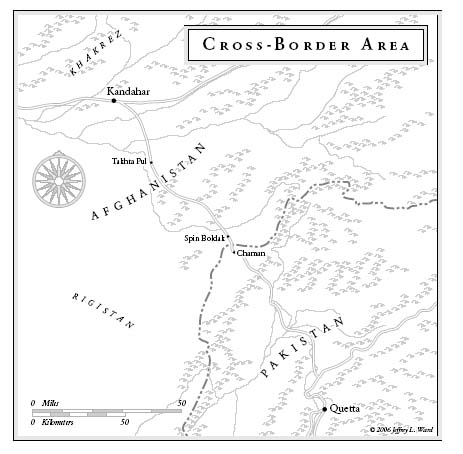

The polluted, crowded metropolis, crawling with disaffected Afghan refugees, had been Akrem's home for several years. Penniless, he had survived on handouts from more fortunate countrymen, among them, future Afghan President Hamid Karzai. He had not even had the means to send for his family; his wife and a little boy and girl remained inside Afghanistan, tucked away on that windswept plateau in Khakrez.

Akrem had been thrust into this humiliating position by a principle: his early and implacable opposition to the Taliban. In 1994, when the black-robed militiamen were rattling the gates of Kandahar, Akrem had quarreled with his own tribal elder about it, through heated nights of palavers. That elder was Mullah Naqib, the same thick-bearded Mullah Naqib who, the day of Akrem's death, had stood at the left turn in Arghandab; the same Mullah Naqib by whose side Akrem had weathered the decade-long war of resistance against the Soviets. That late summer of 1994, Mullah Naqib was going to allow the Taliban into Kandahar. And Akrem refused to be a part of it. The council meetings among the leaders of their powerful Alokozai tribe were tempestuous. In the end, Akrem and his friends were dissuaded from open mutiny. Instead, they held out for weeks in nearby Helmand, then, defeated, left their native Afghan south.

Akrem made his way northwards, spent time fighting against the Taliban alongside the legendary leader of what came to be called the Northern Alliance, Ahmad Shah Massoud. He went to Iran to try to rally Afghan refugees from his own Pashtun ethnic group to the anti-Taliban cause. And at last he landed, impotent, in Quetta. For Akrem too, 9/11âwith all its horrorâwas like the crack of a starting gun. This was it. He knew it. This was the end of the hated Taliban regime.

Akrem was right: the U.S. government moved fast. CIA agents were dropped almost immediately into northern Afghanistan, with briefcases of money, to set about buying allies. Other officials sent out feelers to their contacts in the south, primarily in Quetta, Pakistan.

Alongside the thousands of day laborers, bakers, trinket sellers, hustlers, and Taliban recruiting agents who clogged the streets of Quetta's Pashtunabad neighborhoodâthe flotsam of Afghanistan's various warsâa community of Afghan elites had also taken up quarters in the Pakistani town: engineers, many of them, the heads of humanitarian organizations or demining agencies, former officials of political factions, former resistance commanders like Akrem. It was to this community that the U.S. government turned after 9/11 in its search for anti-Taliban proxies to work with.

Two sharply contrasting candidates quickly emerged: dapper, bald-headed Hamid Karzai, whose father had been speaker of the Afghan National Assembly in the golden age, before a 1970s Communist coup, and Gul Agha Shirzai, an uncouth former Kandahar provincial governor who had presided over unspeakable chaos there in the early 1990sâthe same Shirzai who showed up at Akrem's burial.

American planners decided to enroll them both. The notion was to mount a pincer operation against the Taliban stronghold of Kandahar. Karzai would sneak inside Afghanistan, pass Kandahar, then work his way back down toward it from the north, gathering followers. Gul Agha Shirzai would collect some fighters of his own, and push up toward the city from the south.

It was Hamid Karzai who first called Akrem and asked him to stop by his house, in a leafy Quetta neighborhood. This was a day or two after U.S. jets had started bombing, in early October.

“We're going in,” Karzai told Akrem, as they sat together privately in an upstairs room. “I need you to organize some fighters.” Armies, in Afghanistan, are personal affairs. Each commander brings his own liege men.

Karzai gave Akrem 300,000 Pakistani rupees, the standard commander's share. “We'll talk later,” Karzai assured him breezily. Akrem contained his explosion of energy, focused it down to a burning point, like sunlight through a magnifying glass.

But suddenly Karzai was gone, vanished inside Afghanistan without warning. Akrem was left behind, frustrated, humiliated again.

Then Gul Agha Shirzai came to him for help with the other arm of the pincer, the thrust toward Kandahar from the south. Akrem mistrusted the man. They had had some run-ins back when Shirzai was governor; Akrem had reason to doubt his seriousness. “You're not putting me on?” Akrem challenged, his face like a gathering storm.

“Not a bit,” the former governor swaggered. “The Americans have promised more than a million dollars for this job. They told me that when we get to the border, every vehicle but ours will be bombed. Only we will be able to move.”

A “good-looking young American” was sitting in on this meeting, Akrem told me. He was wearing Kandahari clothes, the front of his tunic glistening with intricate local embroidery. The American didn't interject into the conversation, and Shirzai introduced him with an improbable title, a journalist, or the neighbor of a friend. “From this,” said Akrem, “I knew he was CIA.”

Despite his misgivings, Akrem was not about to miss this chance to help finish off the Taliban. With Hamid Karzai already deployed, Shirzai's was the only game in town. Akrem signed on with Gul Agha Shirzai.

A professional soldier, graduate of the national military academy, a veteran of fighting against both the Soviets and the Taliban, Akrem immediately flipped to combat mode. “We asked Gul Agha Shirzai for details: Who would give us food, who would take our wounded back to Pakistan to the hospital, what was the budget, who was providing the money, what kind of weapons we would have. But he wouldn't give us anything solid.” Akrem remembered the former governor making two trips to Pakistan's capital, Islamabad, during those weeks. A State Department official told me years later that Pakistani intelligence officers introduced Gul Agha Shirzai at the U.S. embassy there, launching his career as an anti-Taliban proxy.

On October 23, 2001, just before I arrived in Quetta, Shirzai was boasting to the

Los Angeles Times

that he could raise 5,000 fighters. “We are ready to move to Kandahar and get rid of the evil there,” he told reporter Tyler Marshall. “Our men are inside and ready.” But Shirzai swore he wanted no role in a post-Taliban government. “I don't have any desire for this,” he insisted. “I want to work for a more national, more liberal, more developed Afghanistan.”

1

Not a week after that article came out, I was checking in at the Serena Hotel to begin covering the drive to oust the Taliban. A reporter's first imperative upon landing in a beat is to develop “sources.” That means striking up acquaintanceships with people who are part of the story, and who, for whatever reason, wish to talk about it. It took awhile, after I fused into the mass of my colleagues grappling to report the same story, but eventually I found one.

It was not Akrem. I would not meet him till later. Those early days, my source was a fighter I discovered in a public call office

2

in Chaman, the Pakistani border town that rubs up against Afghanistan with the greedy voluptuousness of a spoiled cat. His name is Mahmad Anwar. He was a small-time commander also with Shirzai's operation, and I relied on him for my account of it. He became a friend.

He proved to be a very good friend, and I never think of him with anything but gratitude and warmthâeven though I discovered later that he had pulled my leg with a charming shamelessness back then, recounting the events not as they had actually transpired, but as Shirzai and his American advisers wished people to think they had. He took a boyish delight in the bright and convincing colors he threaded through the tapestry he wove for me.

When I asked Mahmad Anwar, months later, to tell me the

real

story of the move on Kandahar, he agreed with relish. He recalled the excited preparations for the strike against the Taliban capital. “We met secretly at Gul Agha Shirzai's house,” he recounted. It would have been about October 12, 2001.

It was a solemn session, as the fighter recalled it. Just three men were there. Taking turns in a tiled bathroom, they accomplished the ablutions Muslims perform before prayer, rinsing their mouths and nostrils and their faces, splashing water with a practiced ritual grace on their arms to the elbows, their hair, their ears, their feet. Next, they took a copy of the Qur'an down from its niche in a wall. Every Afghan house has one, placed aloft, above any other book.

Shirzai unfolded the cloth that was wrapped around the holy book to protect it from the ever-present dust, touched the volume to his lips, and the three men placed their hands upon it.

“By God Almighty, we will fight the Taliban to our deaths, if we must. And if, when we defeat them and they are gone, we are still alive, we will turn over the government to educated people. This by God we vow.”

Mahmad Anwar darted me a look to be sure I grasped the significance: “It was a sacred oath. We swore to surrender our weapons and go home once the Taliban were done for.”

Such was the mood of self-sacrifice, and the feeling of optimism about the implications of the coming Pax Americana, as many Afghans remember it. In that pregnant moment, they abruptly shed their bitterly earned cynicism. They were electrified by the belief that, with American help, the nightmare was going to end, and they would at last be able to lay the foundations of the kind of Afghan state they dreamed of: one united under a qualified, responsible government.

Grasping a wad of bills in his left hand, Gul Agha Shirzai licked a finger and paged through them with his right, counting out about $5,000 in Pakistani rupees for Mahmad Anwar, to pay for his men and their supplies. As the meeting wound up, Mahmad Anwar warned Shirzai: “Do not tell Pakistan what we are doing.”

The role of Pakistan in Afghan affairs is one of the most contentious issues in Kandahar, and indeed throughout much of Afghanistan. After more than two decades in which the Pakistani government has meddled industriously in the destiny of their country, almost all Afghansâeven those who might once have benefitedâmistrust the motives of their southern neighbor.

The Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979. During the savage decade-long war that followed, Pakistan gave aid and shelter to Afghanistan's anti-Soviet resistance, not to mention to millions of Afghan civilians who fled the carnage. Still, most Afghans think that Pakistani officials tried to determine the political results of that war, tried to replace the Soviet puppet at the head of the Afghan state with a puppet of their own. And Afghans resent it. They resent what feels like Pakistan's effort to run their country's economy. They breathe on the embers of a boundary dispute, “temporarily” settled more than a century ago, but in their view still legally open. And they resent the swarms of intelligence agents that Pakistan dispatches to Afghanistan in the guise of students, manual laborers, diplomats, and even Afghan officials, won over or bought during years of exile.

If the Pakistani authorities got mixed up in the anti-Taliban offensive, my border-dwelling friend Mahmad Anwar feared, it would mean danger for him and the rest of the force. For Pakistan had supported the Taliban regime from its very inception. From his vantage point in Chaman, Mahmad Anwar had observed the kind of assistance the Pakistani army and intelligence agency had provided the Taliban over the years. And now, in the wake of 9/11, the Pakistani state apparatus was suddenly turning on its black-turbaned protégés? Converting to the antiterror cause? The switch was suspect in most Afghans' view. Mahmad Anwar was sure that he and his men would be ambushed and shot to pieces if Pakistani spies found out about their plans. Or even if the fighters did survive, a Pakistani connection with their activities must hide some ulterior motive, Mahmad Anwar believed.

Shirzai nodded absently at his warning, and the men filed downstairs, where they bumped into a tall Westernerâprobably Akrem's “good-looking young American.” Shirzai introduced him as “an envoy from the forces in the Gulf.” The presence of this man, at such an early stage, indicates how much it was at U.S. bidding that Shirzai rounded up his force at all. On his own, Kandaharis assure me, Shirzai had no followers. Only U.S. dollars, transformed into the grubby bills he had just counted out for Mahmad Anwar, allowed him to buy some.

About a month after that meeting, on November 12, 2001, a messenger arrived at Mahmad Anwar's house: one of Gul Agha's men. The rendezvous is tonight, he told Mahmad Anwar, at the crossroads where the Gulistan road branches off from the blacktop, halfway to the Afghan border. Be there by eleven. And the messenger was gone, off to inform other commanders.

The dozens of assorted fighters left Quetta a little before 10:00

P

.

M

.âunder the noses of more than a hundred foreign journalists, not one of whom got the story. Pulling up at the turnoff, Mahmad Anwar gasped. At the head of a line of vehicles, two Pakistani army trucks were idling.

“Yeah, sure, we tried to hide from the Pakistanis,” he remarked to his men. “But here they are.”

It is hard to believe that Mahmad Anwar or anyone else involved really thought it possible to keep this venture secret, given the legendary omniscience of the Pakistani intelligence agency, the ISI, and given the close U.S.âPakistan cooperation on the anti-Taliban effort. Still, the overt collaboration was a sore point with the numerous Afghans who knew about it at the time.