The Purple Decades (15 page)

Read The Purple Decades Online

Authors: Tom Wolfe

“Anyway, that thing brought us tremendous publicity. Not long after that I was on the Mike Wallace show on television. Wallace was known as the great prosecutor then or something like that.” Inquisitor? “Yeah, one of those things. There was nothing prearranged on that show. All I knew was that he would really try to let me have it. So he starts after me right away. He's very sarcastic. âWhy don't you admit it, Harrison, that so-called shooting in the Dominican Republic was a fake, a publicity stunt, wasn't it? You weren't shot at all, were you?' So I said to him, Would you know a bullet wound if you saw one?' He says, âYeah.' So I start taking off my shirt right there in front of the camera. Those guys didn't know what to do, die or play organ music. I can see the cameramen and everybody is running around the studio like crazy. Well, I have this big mole on my back, a birthmark, and the cameramen are all so excited, they think that's the bullet hole and they put the camera right on that. Well, that mole's the size

of a nickel, so on television it looked like I'd been shot clean through with a cannon! That was funny. They never heard the end of it, about that show!”

of a nickel, so on television it looked like I'd been shot clean through with a cannon! That was funny. They never heard the end of it, about that show!”

All these things kept happening, Harrison said. His life was always full of this drama, it was like living in the middle of a hurricane. It finally wore him out, he is saying. “It wasn't the libel suits.

“Some of these people we wrote about would be very indignant at first, but I knew goddamned well it was a beautiful act. What they really wanted was

another

story in

Confidential.

It was great publicity for them. You couldn't put out a magazine like

Confidential

again. You know why? Because all the movie stars have started writing books about

themselves!

Look at the stuff Flynn wrote, and Zsa Zsa Gabor, and all of them. They tell all! No magazine can compete with that. That's what really finished the

Confidential

type of thing.”

another

story in

Confidential.

It was great publicity for them. You couldn't put out a magazine like

Confidential

again. You know why? Because all the movie stars have started writing books about

themselves!

Look at the stuff Flynn wrote, and Zsa Zsa Gabor, and all of them. They tell all! No magazine can compete with that. That's what really finished the

Confidential

type of thing.”

So Harrison retired with his soap-bubble lawsuits and his pile of money to the sedentary life of stock-market investor.

“I got into the stock market quite by accident,” Harrison is saying. “This guy told me of a good stock to invest in, Fairchild Camera, so I bought a thousand shares. I made a quarter of a million dollars the first month! I said to myself, âWhere the hell has

this

business been all my life!'”

this

business been all my life!'”

Harrison's sensational good fortune on the stock market lasted just about that long, one month.

“So I started putting out the one-shots, but there was no

continuity

in them. So then I got the idea of

Inside News

.”

continuity

in them. So then I got the idea of

Inside News

.”

Suddenly Harrison's eyes are fixed on the door. There, by god, in the door is Walter Winchell. Winchell has on his snap-brim police reporter's hat, circa 1924, and an overcoat with the collar turned up. He's scanning the room, like Wild Bill Hickock entering the Crazy Legs Saloon. Harrison gives him a big smile and a huge wave. “There's Walter!” he says.

Winchell gives an abrupt wave with his left hand, keeps his lips set like bowstrings and walks off to the opposite side of Lindy's.

After a while, a waiter comes around, and Harrison says, “Who is Walter with?”

“He's with his granddaughter.”

By and by Harrison, Reggie and I got up to leave, and at the door Harrison says to the maître d':

“Where's Walter?”

“He left a little while ago,” the maitre d' says.

“He was with his granddaughter,” Harrison says.

“Oh, was that who that was,” the maître d' says.

“Yeah,” says Harrison. “It was his granddaughter. I didn't want to disturb them.”

In the cab on the way back to the Madison Hotel Harrison says, “You know, we've got a hell of a cute story in

Inside News

about this girl who's divorcing her husband because all he does at night is watch the Johnny Carson show and then he just falls into bed and goes to sleep and won't even give her a tumble. It's a very cute story, very inoffensive.

Inside News

about this girl who's divorcing her husband because all he does at night is watch the Johnny Carson show and then he just falls into bed and goes to sleep and won't even give her a tumble. It's a very cute story, very inoffensive.

“Well, I have an idea. I'm going to take this story and show it to Johnny Carson. I think he'll go for it. Maybe we can work out something. You know, he goes through the audience on the show, and so one night Reggie can be in the audience and she can have this copy of

Inside News

with her. When he comes by, she can get up and say, âMr. Carson, I see by this newspaper here,

Inside News

, that your show is breaking up happy marriages,' or something like that. And then she can hold up

Inside News

and show him the story and he can make a gag out of it. I think he'll go for it. What do you think? I think it'll be a hell of a cute stunt.”

Inside News

with her. When he comes by, she can get up and say, âMr. Carson, I see by this newspaper here,

Inside News

, that your show is breaking up happy marriages,' or something like that. And then she can hold up

Inside News

and show him the story and he can make a gag out of it. I think he'll go for it. What do you think? I think it'll be a hell of a cute stunt.”

Nobody says anything for a minute, then Harrison says, sort of moodily,

“I'm not putting out

Inside News

for the money. I just want to proveâthere are a lot of people say I was just a flash in the pan. I just want to prove I can do it again.”

Inside News

for the money. I just want to proveâthere are a lot of people say I was just a flash in the pan. I just want to prove I can do it again.”

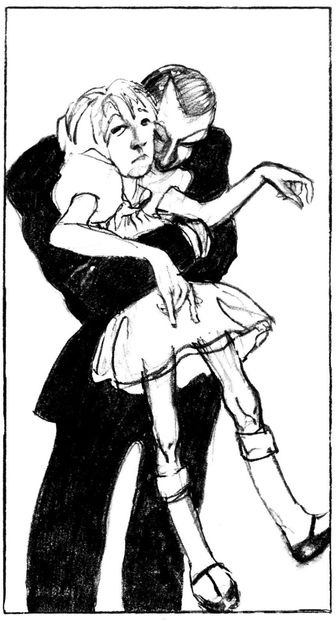

The Evolution of the Species: The Twelve-Year-Old and Her Father's Love

1951

Â

“Poor Daddy, he doesn't even know how Oedipal this all is.”

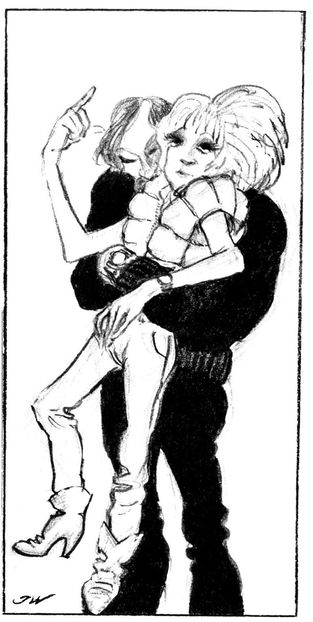

1981

Â

“My other daddies liked to do this, too. Hurts your freakin' ribs.”

L

ove! Attar of libido in the air! It is 8:45 A.M. Thursday morning in the IRT subway station at 50th Street and Broadway and already two kids are hung up in a kind of herringbone weave of arms and legs, which proves, one has to admit, that love is not

confined

to Sunday in New York. Still, the odds! All the faces come popping in clots out of the Seventh Avenue local, past the King Size Ice Cream machine, and the turnstiles start whacking away as if the world were breaking up on the reefs. Four steps past the turnstiles everybody is already backed up haunch to paunch for the climb up the ramp and the stairs to the surface, a great funnel of flesh, wool, felt, leather, rubber and steaming alumicron, with the blood squeezing through everybody's old sclerotic arteries in hopped-up spurts from too much coffee and the effort of surfacing from the subway at the rush hour. Yet there on the landing are a boy and a girl, both about eighteen, in one of those utter, My Sin, backbreaking embraces.

ove! Attar of libido in the air! It is 8:45 A.M. Thursday morning in the IRT subway station at 50th Street and Broadway and already two kids are hung up in a kind of herringbone weave of arms and legs, which proves, one has to admit, that love is not

confined

to Sunday in New York. Still, the odds! All the faces come popping in clots out of the Seventh Avenue local, past the King Size Ice Cream machine, and the turnstiles start whacking away as if the world were breaking up on the reefs. Four steps past the turnstiles everybody is already backed up haunch to paunch for the climb up the ramp and the stairs to the surface, a great funnel of flesh, wool, felt, leather, rubber and steaming alumicron, with the blood squeezing through everybody's old sclerotic arteries in hopped-up spurts from too much coffee and the effort of surfacing from the subway at the rush hour. Yet there on the landing are a boy and a girl, both about eighteen, in one of those utter, My Sin, backbreaking embraces.

He envelops her not only with his arms but with his chest, which has the American teen-ager concave shape to it. She has her head cocked at a 90-degree angle and they both have their eyes pressed shut for all they are worth and some incredibly feverish action going with each other's mouths. All round them, ten, scores, it seems like hundreds, of faces and bodies are perspiring, trooping and bellying up the stairs with arteriosclerotic grimaces past a showcase full of such novel items as Joy Buzzers, Squirting Nickels, Finger Rats, Scary Tarantulas and spoons with realistic dead flies on them, past Fred's barbershop, which is just off the landing and has glossy photographs of young men with the kind of baroque haircuts one can get in there,

and up onto 50th Street into a madhouse of traffic and shops with weird lingerie and gray hair-dyeing displays in the windows, signs for free teacup readings and a pool-playing match between the Playboy Bunnies and Downey's Showgirls, and then everybody pounds on toward the Time-Life Building, the Brill Building or NBC.

and up onto 50th Street into a madhouse of traffic and shops with weird lingerie and gray hair-dyeing displays in the windows, signs for free teacup readings and a pool-playing match between the Playboy Bunnies and Downey's Showgirls, and then everybody pounds on toward the Time-Life Building, the Brill Building or NBC.

The boy and the girl just keep on writhing in their embroilment. Her hand is sliding up the back of his neck, which he turns when her fingers wander into the intricate formal gardens of his Chicago Boxcar hairdo at the base of the skull. The turn causes his face to start to mash in the ciliated hull of her beehive hairdo, and so she rolls her head 180 degrees to the other side, using their mouths for the pivot. But aside from good hair grooming, they are oblivious to everything but each other. Everybody gives them a once-over. Disgusting! Amusing! How touching! A few kids pass by and say things like “Swing it, baby.” But the great majority in that heaving funnel up the stairs seem to be as much astounded as anything else. The vision of love at rush hour cannot strike anyone exactly as romance. It is a feat, like a fat man crossing the English Channel in a barrel. It is an earnest accomplishment against the tide. It is a piece of slightly gross heroics, after the manner of those knobby, varicose old men who come out from some place in baggy shorts every year and run through the streets of Boston in the Marathon race. And somehow that is the gaffe against love all week long in New York, for everybody, not just two kids writhing under their coiffures in the 50th Street subway station; too hurried, too crowded, too hard, and no time for dalliance. Which explains why the real thing in New York is, as it says in the song, a Sunday kind of love.

There is Saturday, but Saturday is not much better than Monday through Friday. Saturday is the day for errands in New York. More millions of shoppers are pouring in to keep the place jammed up. Everybody is bobbing around, running up to Yorkville to pick up these arty cheeses for this evening, or down to Fourth Avenue to try to find this Van Vechten book,

Parties,

to complete the set for somebody, or off to the cleaner's, the dentist's, the hairdresser's, or some guy's who is going to loan you his station wagon to pick up two flush doors to make tables out of, or over to some place somebody mentioned that is supposed to have fabulous cuts of meat and the butcher wears a straw hat and arm garters and is colorfully rude.

Parties,

to complete the set for somebody, or off to the cleaner's, the dentist's, the hairdresser's, or some guy's who is going to loan you his station wagon to pick up two flush doors to make tables out of, or over to some place somebody mentioned that is supposed to have fabulous cuts of meat and the butcher wears a straw hat and arm garters and is colorfully rude.

True, there is Saturday night, and Friday night. They are fine for dates and good times in New York. But for the dalliance of love, they are just as stupefying and wound up as the rest of the week. On Friday and Saturday nights everybody is making some kind of scene. It may be a cellar cabaret in the Village where five guys from some place talk “Jamaican” and pound steel drums and the Connecticut

teen-agers wear plaid ponchos and knee-high boots and drink such things as Passion Climax cocktails, which are made of apple cider with watermelon balls thrown in. Or it may be some cellar in the East 50's, a discotheque, where the alabaster kids come on in sleeveless minksides jackets, tweed evening dresses and cool-it Modernismus hairdos. But either way, it's a scene, a production, and soon the evening begins to whirl, like the whole world with the bed-spins, in a montage of taxis, slithery legs slithering in, slithery legs slithering out, worsted, pique, grins, eye teeth, glissandos, buffoondos, tips, par lamps, doormen, lines, magenta ropes, white dickies, mirrors and bar bottles, pink men and shawl-collared coats, hatcheck girls and neon peach fingernails, taxis, keys, broken lamps and no coat hangers ⦠.

teen-agers wear plaid ponchos and knee-high boots and drink such things as Passion Climax cocktails, which are made of apple cider with watermelon balls thrown in. Or it may be some cellar in the East 50's, a discotheque, where the alabaster kids come on in sleeveless minksides jackets, tweed evening dresses and cool-it Modernismus hairdos. But either way, it's a scene, a production, and soon the evening begins to whirl, like the whole world with the bed-spins, in a montage of taxis, slithery legs slithering in, slithery legs slithering out, worsted, pique, grins, eye teeth, glissandos, buffoondos, tips, par lamps, doormen, lines, magenta ropes, white dickies, mirrors and bar bottles, pink men and shawl-collared coats, hatcheck girls and neon peach fingernails, taxis, keys, broken lamps and no coat hangers ⦠.

And, then, an unbelievable dawning; Sunday, in New York.

George G., who writes “Z” ads for a department store, keeps saying that all it takes for him is to smell coffee being made at a certain point in the percolation. It doesn't matter where. It could be the worst death-ball hamburger dive. All he has to do is smell it, and suddenly he finds himself swimming, drowning, dissolving in his own reverie of New York's Sunday kind of love.

Anne A.'s apartment was nothing, he keeps saying, and that was the funny thing. She lived in Chelsea. It was this one room with a cameo-style carving of a bored Medusa on the facing of the mantelpiece, this one room plus a kitchen, in a brownstone sunk down behind a lot of loft buildings and truck terminals and so forth. Beautiful Chelsea. But on Sunday morning by 10:30 the sun would be hitting cleanly between two rearview buildings and making it through the old no man's land of gas effluvia ducts, restaurant vents, aerials, fire escapes, stairwell doors, clotheslines, chimneys, skylights, vestigial lightning rods, Mansard slopes, and those peculiarly bleak, filthy and misshapen backsides of New York buildings, into Anne's kitchen.

George would be sitting at this rickety little table with an oilcloth over it. How he goes on about it! The place was grimy. You couldn't keep the soot out. The place was beautiful. Anne is at the stove making coffee. The smell of the coffee being made, just the smell ⦠already he is turned on. She had on a great terrycloth bathrobe with a sash belt. The way she moved around inside that bathrobe with the sun shining in the window always got him. It was the

at

mosphere of the thing. There she was, moving around in that great fluffy bathrobe with the sun hitting her hair, and they had all the time in the world. There wasn't even one flatulent truck horn out on Eighth Avenue. Nobody was clobbering their way down the stairs in high heels out in the hall at 10 minutes to 9.

at

mosphere of the thing. There she was, moving around in that great fluffy bathrobe with the sun hitting her hair, and they had all the time in the world. There wasn't even one flatulent truck horn out on Eighth Avenue. Nobody was clobbering their way down the stairs in high heels out in the hall at 10 minutes to 9.

Anne would make scrambled eggs, plain scrambled eggs, but it was a feast. It was incredible. She would bring out a couple of these little

smoked fish with golden skin and some smoked oysters that always came in a little can with ornate lettering and royal colors and flourishes and some Kissebrot bread and black cherry preserves, and then the coffee. They had about a million cups of coffee apiece, until the warmth seemed to seep through your whole viscera. And then cigarettes. The cigarettes were like some soothing incense. The radiator was always making a hissing sound and then a clunk. The sun was shining in and the fire escapes and effluvia ducts were just silhouettes out there someplace. George would tear off another slice of Kissebrot and pile on some black cherry preserves and drink some more coffee and have another cigarette, and Anne crossed her legs under her terrycloth bathrobe and crossed her arms and drew on her cigarette, and that was the way it went.

smoked fish with golden skin and some smoked oysters that always came in a little can with ornate lettering and royal colors and flourishes and some Kissebrot bread and black cherry preserves, and then the coffee. They had about a million cups of coffee apiece, until the warmth seemed to seep through your whole viscera. And then cigarettes. The cigarettes were like some soothing incense. The radiator was always making a hissing sound and then a clunk. The sun was shining in and the fire escapes and effluvia ducts were just silhouettes out there someplace. George would tear off another slice of Kissebrot and pile on some black cherry preserves and drink some more coffee and have another cigarette, and Anne crossed her legs under her terrycloth bathrobe and crossed her arms and drew on her cigarette, and that was the way it went.

“It was the

torpor

, boy,” he says. “It was beautiful. Torpor is a beautiful, underrated thing. Torpor is a luxury. Especially in this stupid town. There in that kitchen it was like being in a perfect cocoon of love. Everything was beautiful, a perfect cocoon.”

torpor

, boy,” he says. “It was beautiful. Torpor is a beautiful, underrated thing. Torpor is a luxury. Especially in this stupid town. There in that kitchen it was like being in a perfect cocoon of love. Everything was beautiful, a perfect cocoon.”

By and by they would get dressed, always in as shiftless a getup as possible. She would put on a big heavy sweater, a raincoat and a pair of faded slacks that gripped her like neoprene rubber. He would put on a pair of corduroy pants, a crew sweater with moth holes and a raincoat. Then they would go out and walk down to 14th Street for the Sunday paper.

All of a sudden it was great out there on the street in New York. All those damnable millions who come careening into Manhattan all week weren't there. The town was empty. To a man and woman shuffling along there, torpid, in the cocoon of love, it was as if all of rotten Gotham had improved overnight. Even the people looked better. There would be one of those old dolls with little flabby arms all hunched up in a coat of pastel oatmeal texture, the kind whose lumpy old legs you keep seeing as she heaves her way up the subway stairs ahead of you and holds everybody up because she is so flabby and decrepit ⦠and today, Sunday, on good, clean, empty 14th Street, she just looked like a nice old lady. There was no one around to make her look slow, stupid, unfit, unhip, expendable. That was the thing about Sunday. The weasel millions were absent. And Anne walking along beside him with a thready old pair of slacks gripping her like neoprene rubber looked like possibly the most marvelous vision the world had ever come up with, and the cocoon of love was perfect. It was like having your cake and eating it, too. On the one hand, here it was, boy, the prize: New York. All the buildings, the Gotham spires, were sitting up all over the landscape in silhouette like ikons representing all that was great, glorious and triumphant in New York. And, on the other hand, there were no weasel millions bellying

past you and eating crullers on the run with the crumbs flaking off the corners of their mouths as a reminder of how much

Angst

and

Welthustle

you had to put into the town to get any of that out of it for yourself. All there was was the cocoon of love, which was complete. It was like being inside a scenic Easter Egg where you look in and the Gotham spires are just standing there like a little gemlike backdrop.

past you and eating crullers on the run with the crumbs flaking off the corners of their mouths as a reminder of how much

Angst

and

Welthustle

you had to put into the town to get any of that out of it for yourself. All there was was the cocoon of love, which was complete. It was like being inside a scenic Easter Egg where you look in and the Gotham spires are just standing there like a little gemlike backdrop.

By and by the two of them would be back in the apartment sprawled out on the floor rustling through the Sunday paper, all that even black ink appliquéd on big fat fronds of paper. Anne would put an E. Power Biggs organ record on the hi-fi, and pretty soon the old trammeler's bass chords would be vibrating through you as if he had clamped a diathermy machine on your solar plexus. So there they would be, sprawled out on the floor, rustling through the Sunday paper, getting bathed and massaged by E. Power Biggs' sonic waves. It was like taking peyote or something. This marvelously high feeling would come over them, as though they were psychedelic, and the most commonplace objects took on this great radiance and significance. It was like old Aldous Huxley in his drug experiments, sitting there hooking down peyote buttons and staring at a clay geranium pot on a table, which gradually became the most fabulous geranium pot in God's world. The way it curved ⦠why, it curved 360 d-e-g-r-e-e-s! And the clay ⦠why, it was the color of the earth itself! And the top ⦠It had a r-i-m on it! George had the same feeling. Anne's apartment ⦠it was hung all over the place with the usual New York working girl's modern prints, the Picasso scrawls, the Mondrians curling at the corners ⦠somehow nobody ever gets even a mat for a Mondrian print ⦠the Toulouse-Lautrecs with that guy with the chin kicking his silhouette leg, the Klees, that Paul Klee is cute ⦠why, all of a sudden these were the most beautiful things in the whole hagiology of art ⦠the way that guy with the chin k-i-c-k-s t-h-a-t l-e-g, the way that Paul Klee h-i-t-s t-h-a-t b-a-l-l ⦠the way that apartment just wrapped around them like a cocoon, with lint under the couch like angel's hair, and the plum cover on the bed lying halfway on the floor in folds like the folds in a Tiepolo cherub's silks, and the bored Medusa on the mantelpiece looking like the most splendidly, gloriously b-o-r-e-d Medusa in the face of time!

“Now, that was love,” says George, “and there has never been anything like it. I don't know what happens to it. Unless it's Monday. Monday sort of happens to it in New York.”

The New Cookie

Other books

Wicked Earl Seeks Proper Heiress by Sara Bennett

Not Looking for Love: A Cowboy Romance by Martini, Mae

Mary Magdalene: A Novel by Diana Wallis Taylor

Aquatic Attraction by Charlie Richards

The Centurions by Jean Larteguy

HCC 115 - Borderline by Lawrence Block

Forty Thieves by Thomas Perry

Something Like Normal by Trish Doller

For Love or Money by Tara Brown

Service Dress Blues by Michael Bowen