The Purple Decades (49 page)

Read The Purple Decades Online

Authors: Tom Wolfe

The Invisible Wife

T

he Invisible Wife arrived at the party with Her Husband, but Her Husband was soon vectored off into another room by one of his great manswarm of chums, who began pouring an apparently delicious story down his ear.

he Invisible Wife arrived at the party with Her Husband, but Her Husband was soon vectored off into another room by one of his great manswarm of chums, who began pouring an apparently delicious story down his ear.

The Invisible Wife had gone to the trouble of getting a sideswept multi-chignon hairdo and a Rue St. Honoré Chloe dress with enormous padded shoulders surmounted by piles of beading sewn on as thick as the topping on a peach melba precisely in order to cease being invisible. But from the moment the social current swept her into the path of Her Husband's business friend Earl, her intracranial alarm system warned her that

it

would happen, nonetheless.

it

would happen, nonetheless.

After all, she had only been introduced to Earl four times in the past, at four different parties, and this time Her Husband was in another room.

“Hello, Earl,” she said clearly and brightly, looking him straight in the eyes.

Earl's lips spread across his face in a great polyurethaned smile. But his eyes were pure panic. They contracted into two little round balls, like a pair of Gift Shop Lucite knickknacks. “Mayday!” they said. “Code Blue! I've met this woman somewhere, but who inna namea Christ is she?”

“Ohh!” he said. “Ahh! Howya doin'! Yes!â”

The little Lucite balls were bouncing all over her, over her hairdo, chignon by chignon, over her blazing shoulders, her dress, her Charles Jourdan shoes, searching for a clue.

“How're the children!” he exclaimed finally, taking a desperate chance.

This was the deepest wound of all for the Invisible Wife. The man had just passed his eyes over $1

650 worth of Franco-American chic and decided that the main thing about her was ⦠she looked

650 worth of Franco-American chic and decided that the main thing about her was ⦠she looked

matronly

.

650 worth of Franco-American chic and decided that the main thing about her was ⦠she looked

650 worth of Franco-American chic and decided that the main thing about her was ⦠she lookedmatronly

.

How're the children â¦

“They've got Legionnaire's disease,” she wanted to say, because she knew these people didn't listen to the Invisible Wife. But she went ahead and did the usual.

“They've got Legionnaire's disease,” she wanted to say, because she knew these people didn't listen to the Invisible Wife. But she went ahead and did the usual.

“Oh, they're fine,” she said.

“That's great!” Earl said. “That's great!” He kept saying “That's great” and looking straight through her, frantically trying to devise some way to remove himself from her presence before somebody he knew approached and he was faced with the impossible task of

introducing

her.

introducing

her.

At dinner the Invisible Wife sat next to a man who was an investment counselor with an evident interest in convertible debentures.

Convertible debentures!

An adrenal surge of hope rose in the Invisible Wife. Somewhere down Memory Lane she had actually picked up a conversational nugget concerning convertible debentures. This nugget had to do with an extraordinary mathematician from MIT named Edward O. Thorp who, using computers, had devised an

extrinsic formula

for beating the stock market by playing convertible debentures. So she introduced her conversational nuggetâEdward O. Thorp

and the Convertible Debenturesâinto the conversation. She dropped it in, just so, ever so lightly; for, being a veteran of dinners like this, she knew that a woman can ask questions, introduce topics, interject the occasional

bon mot

, even deliver a punch line now and again, but she is not to launch into disquisitions or actually

tell long stories

herself.

Convertible debentures!

An adrenal surge of hope rose in the Invisible Wife. Somewhere down Memory Lane she had actually picked up a conversational nugget concerning convertible debentures. This nugget had to do with an extraordinary mathematician from MIT named Edward O. Thorp who, using computers, had devised an

extrinsic formula

for beating the stock market by playing convertible debentures. So she introduced her conversational nuggetâEdward O. Thorp

and the Convertible Debenturesâinto the conversation. She dropped it in, just so, ever so lightly; for, being a veteran of dinners like this, she knew that a woman can ask questions, introduce topics, interject the occasional

bon mot

, even deliver a punch line now and again, but she is not to launch into disquisitions or actually

tell long stories

herself.

“Edward O. Thorp!” the Investment Counselor said. “Oh my God!” âand the Invisible Wife was pleased to see that this topic absolutely delighted the Investment Counselor. He launched into an anecdote that lit up his irises like a pair of bed-lamp high-intensity bulbs. There is nothing that a man hungers for more at dinner than to dominate the conversation in his sector of the table.

The Invisible Wife soon noticed, however, that when the man sitting on the other side of her turned their way to listen in, the Investment Counselor looked right past her and directed the entire story into

the man's

face. Not only that, when this man was distracted for a moment by the woman on his other side, the Investment Counselor stopped talking, as if his switch had been turned off. He stopped in mid-sentence, and his eyes clouded up, and he just waited, with his mouth open.

the man's

face. Not only that, when this man was distracted for a moment by the woman on his other side, the Investment Counselor stopped talking, as if his switch had been turned off. He stopped in mid-sentence, and his eyes clouded up, and he just waited, with his mouth open.

After all, why waste a terrific yarn on an Invisible Wife?

Â

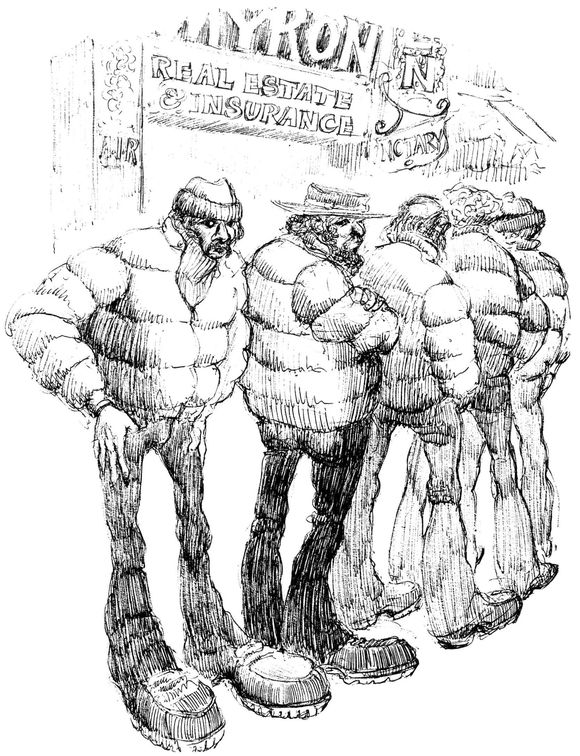

Artistic Vision

Artists from Cincinnati and Cleveland, hot off the Carey airport bus, line up in Soho looking for the obligatory loft.

*

P

eople don't read the morning newspaper, Marshall McLuhan once said, they slip into it like a warm bath. Too true, Marshall! Imagine being in New York City on the morning of Sunday, April 28, 1974, like I was, slipping into that great public bath, that vat, that spa, that regional physiotherapy tank, that White Sulphur Springs, that Marienbad, that Ganges, that River Jordan for a million souls which is the Sunday

New York Times

. Soon I was submerged, weightless, suspended in the tepid depths of the thing, in Arts & Leisure, Section 2, page 19, in a state of perfect sensory deprivation, when all at once an extraordinary thing happened:

eople don't read the morning newspaper, Marshall McLuhan once said, they slip into it like a warm bath. Too true, Marshall! Imagine being in New York City on the morning of Sunday, April 28, 1974, like I was, slipping into that great public bath, that vat, that spa, that regional physiotherapy tank, that White Sulphur Springs, that Marienbad, that Ganges, that River Jordan for a million souls which is the Sunday

New York Times

. Soon I was submerged, weightless, suspended in the tepid depths of the thing, in Arts & Leisure, Section 2, page 19, in a state of perfect sensory deprivation, when all at once an extraordinary thing happened:

I

noticed something!

noticed something!

Yet another clam-broth-colored current had begun to roll over me, as warm and predictable as the Gulf Stream ⦠a review, it was, by the

Times's

dean of the arts, Hilton Kramer, of an exhibition at Yale University of “Seven Realists,” seven realistic painters ⦠when I was

jerked alert

by the following:

Times's

dean of the arts, Hilton Kramer, of an exhibition at Yale University of “Seven Realists,” seven realistic painters ⦠when I was

jerked alert

by the following:

“Realism does not lack its partisans, but it does rather conspicuously lack a persuasive theory. And given the nature of our intellectual commerce with works of art, to lack a persuasive theory is to lack something crucialâthe means by which our experience of individual works is joined to our understanding of the values they signify.”

Now, you may say, My God, man! You woke up over

that

? You forsook your blissful coma over a mere swell in the sea of words?

that

? You forsook your blissful coma over a mere swell in the sea of words?

But I knew what I was looking at. I realized that without making the slightest effort I had come upon one of those utterances in search of which psychoanalysts and State Department monitors of the Moscow or Belgrade press are willing to endure a lifetime of tedium: namely,

the seemingly innocuous

obiter dicta,

the words in passing, that give the game away.

the seemingly innocuous

obiter dicta,

the words in passing, that give the game away.

From

The Painted Word

, pp. 3-23 (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1975). First published in

Harper's,

April 1975.

The Painted Word

, pp. 3-23 (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1975). First published in

Harper's,

April 1975.

What I saw before me was the critic-in-chief of

The New York Times

saying: In looking at a painting today, “to lack a persuasive theory is to lack something crucial.” I read it again. It didn't say “something helpful” or “enriching” or even “extremely valuable.” No, the word was

crucial.

The New York Times

saying: In looking at a painting today, “to lack a persuasive theory is to lack something crucial.” I read it again. It didn't say “something helpful” or “enriching” or even “extremely valuable.” No, the word was

crucial.

In short: frankly, these days, without a theory to go with it, I can't see a painting.

Then and there I experienced a flash known as the

Aha!

phenomenon, and the buried life of contemporary art was revealed to me for the first time. The fogs lifted! The clouds passed! The motes, scales, conjunctival bloodshots, and Murine agonies fell away!

Aha!

phenomenon, and the buried life of contemporary art was revealed to me for the first time. The fogs lifted! The clouds passed! The motes, scales, conjunctival bloodshots, and Murine agonies fell away!

All these years, along with countless kindred souls, I am certain, I had made my way into the galleries of Upper Madison and Lower SoHo and the Art Gildo Midway of Fifty-seventh Street, and into the museums, into the Modern, the Whitney, and the Guggenheim, the Bastard Bauhaus, the New Brutalist, and the Fountainhead Baroque, into the lowliest storefront churches and grandest Robber Baronial temples of Modernism. All these years I, like so many others, had stood in front of a thousand, two thousand, God-knows-how-many thousand Pollocks, de Koonings, Newmans, Nolands, Rothkos, Rauschenbergs, Judds, Johnses, Olitskis, Louises, Stills, Franz Klines, Frankenthalers, Kellys, and Frank Stellas, now squinting, now popping the eye sockets open, now drawing back, now moving closerâwaiting, waiting, forever waiting for â¦

it

⦠for

it

to come into focus, namely, the visual reward (for so much effort) which must be there, which everyone

(tout le monde)

knew to be thereâwaiting for something to radiate directly from the paintings on these invariably pure white walls, in this room, in this moment, into my own optic chiasma. All these years, in short, I had assumed that in art, if nowhere else, seeing is believing. Wellâhow very shortsighted! Now, at last, on April 28, 1974

I could

I could

see

. I had gotten it backward all along. Not “seeing is believing,” you ninny, but “believing is seeing,” for

Modern Art has become completely literary: the paintings and other works exist only to illustrate the text.

it

⦠for

it

to come into focus, namely, the visual reward (for so much effort) which must be there, which everyone

(tout le monde)

knew to be thereâwaiting for something to radiate directly from the paintings on these invariably pure white walls, in this room, in this moment, into my own optic chiasma. All these years, in short, I had assumed that in art, if nowhere else, seeing is believing. Wellâhow very shortsighted! Now, at last, on April 28, 1974

I could

I couldsee

. I had gotten it backward all along. Not “seeing is believing,” you ninny, but “believing is seeing,” for

Modern Art has become completely literary: the paintings and other works exist only to illustrate the text.

Â

Like most sudden revelations, this one left me dizzy. How could such a thing be? How could Modern Art be

literary?

As every art-history student is told, the Modern movement began about 1900 with a complete rejection of the literary nature of academic art, meaning the sort of realistic art which originated in the Renaissance and which the various national academies still held up as the last word.

literary?

As every art-history student is told, the Modern movement began about 1900 with a complete rejection of the literary nature of academic art, meaning the sort of realistic art which originated in the Renaissance and which the various national academies still held up as the last word.

Literary

became a code word for all that seemed hopelessly retrograde

about realistic art. It probably referred originally to the way nineteenth-century painters liked to paint scenes straight from literature, such as Sir John Everett Millais's rendition of Hamlet's intended,

Ophelia,

floating dead (on her back) with a bouquet of wildflowers in her death grip. In time,

literary

came to refer to realistic painting in general. The idea was that half the power of a realistic painting comes not from the artist but from the sentiments the viewer hauls along to it, like so much mental baggage. According to this theory, the museum-going public's love of, say, Jean François Millet's

The Sower

has little to do with Millet's talent and everything to do with people's sentimental notions about The Sturdy Yeoman. They make up a little story about him.

became a code word for all that seemed hopelessly retrograde

about realistic art. It probably referred originally to the way nineteenth-century painters liked to paint scenes straight from literature, such as Sir John Everett Millais's rendition of Hamlet's intended,

Ophelia,

floating dead (on her back) with a bouquet of wildflowers in her death grip. In time,

literary

came to refer to realistic painting in general. The idea was that half the power of a realistic painting comes not from the artist but from the sentiments the viewer hauls along to it, like so much mental baggage. According to this theory, the museum-going public's love of, say, Jean François Millet's

The Sower

has little to do with Millet's talent and everything to do with people's sentimental notions about The Sturdy Yeoman. They make up a little story about him.

What was the opposite of literary painting? Why,

l'art pour l'art,

form for the sake of form, color for the sake of color. In Europe before 1914, artists invented Modern styles with fanatic energyâFauvism, Futurism, Cubism, Expressionism, Orphism, Suprematism, Vorticism âbut everybody shared the same premise: henceforth, one doesn't paint “

about

anything, my dear aunt,” to borrow a line from a famous

Punch

cartoon. One just

paints

. Art should no longer be a mirror held up to man or nature. A painting should compel the viewer to see it for what it is: a certain arrangement of colors and forms on a canvas.

l'art pour l'art,

form for the sake of form, color for the sake of color. In Europe before 1914, artists invented Modern styles with fanatic energyâFauvism, Futurism, Cubism, Expressionism, Orphism, Suprematism, Vorticism âbut everybody shared the same premise: henceforth, one doesn't paint “

about

anything, my dear aunt,” to borrow a line from a famous

Punch

cartoon. One just

paints

. Art should no longer be a mirror held up to man or nature. A painting should compel the viewer to see it for what it is: a certain arrangement of colors and forms on a canvas.

Artists pitched in to help make theory. They loved it, in fact. Georges Braque, the painter for whose work the word

Cubism

was coined, was a great formulator of precepts:

Cubism

was coined, was a great formulator of precepts:

“The painter thinks in forms and colors. The aim is not to

reconstitute

an anecdotal fact but to

constitute

a pictorial fact.”

reconstitute

an anecdotal fact but to

constitute

a pictorial fact.”

Today this notion, this protestâwhich it was when Braque said it âhas become a piece of orthodoxy. Artists repeat it endlessly, with conviction. As the Minimal Art movement came into its own in 1966, Frank Stella was saying it again:

“My painting is based on the fact that only what can be seen there

is

there. It really is an object ⦠What you see is what you see.”

is

there. It really is an object ⦠What you see is what you see.”

Such emphasis, such certainty! What a head of steamâwhat patriotism an idea can build up in three-quarters of a century! In any event, so began Modern Art and so began the modern art of Art Theory. Braque, like Frank Stella, loved theory; but for Braque, who was a Montmartre boho

u

of the primitive sort, art came first. You can be sure the poor fellow never dreamed that during his own lifetime that order would be reversed.

u

of the primitive sort, art came first. You can be sure the poor fellow never dreamed that during his own lifetime that order would be reversed.

All the major Modern movements except for De Stijl, Dada, Constructivism, and Surrealism began before the First World War, and yet they all

seem

to come out of the 1920s. Why? Because it was in the 1920s that Modern Art achieved social chic in Paris, London, Berlin, and New York. Smart people talked about it, wrote about it, enthused over it, and borrowed from it, as I say; Modern Art achieved the ultimate social acceptance: interior decorators did knock-offs of it in Belgravia and the sixteenth arrondissement.

seem

to come out of the 1920s. Why? Because it was in the 1920s that Modern Art achieved social chic in Paris, London, Berlin, and New York. Smart people talked about it, wrote about it, enthused over it, and borrowed from it, as I say; Modern Art achieved the ultimate social acceptance: interior decorators did knock-offs of it in Belgravia and the sixteenth arrondissement.

Things like knock-off specialists, money, publicity, the smart set, and Le Chic shouldn't count in the history of art, as we all knowâbut, thanks to the artists themselves, they do. Art and fashion are a two-backed beast today; the artists can yell at fashion, but they can't move out ahead. That has come about as follows:

By 1900 the artist's arenaâthe place where he seeks honor, glory, ease, Successâhad shifted twice. In seventeenth-century Europe the artist was literally, and also psychologically, the house guest of the nobility and the royal court (except in Holland); fine art and court art were one and the same. In the eighteenth century the scene shifted to the

salons,

in the homes of the wealthy bourgeoisie as well as those of aristocrats, where Culture-minded members of the upper classes held regular meetings with selected artists and writers. The artist was still the Gentleman, not yet the Genius. After the French Revolution, artists began to leave the

salons

and join

cénacles,

which were fraternities of like-minded souls huddled at some place like the Café Guerbois rather than a town house; around some romantic figure, an artist rather than a socialite, someone like Victor Hugo, Charles Nodier, Théophile Gautier, or, later, Edouard Manet. What held the

cénacles

together was that merry battle spirit we have all come to know and love:

épatez la bourgeoisie

, shock the middle class. With Gautier's

cénacle

especially ⦠with Gautier's own red vests, black scarves, crazy hats, outrageous pronouncements, huge thirsts, and ravenous groin ⦠the modern picture of The Artist began to form: the poor but free spirit, plebeian but aspiring only to be classless, to cut himself forever free from the bonds of the greedy and hypocritical bourgeoisie, to be whatever the fat burghers feared most, to cross the line wherever they drew it, to look at the world in a way they couldn't

see

, to be high, live low, stay young foreverâin short, to be the bohemian.

salons,

in the homes of the wealthy bourgeoisie as well as those of aristocrats, where Culture-minded members of the upper classes held regular meetings with selected artists and writers. The artist was still the Gentleman, not yet the Genius. After the French Revolution, artists began to leave the

salons

and join

cénacles,

which were fraternities of like-minded souls huddled at some place like the Café Guerbois rather than a town house; around some romantic figure, an artist rather than a socialite, someone like Victor Hugo, Charles Nodier, Théophile Gautier, or, later, Edouard Manet. What held the

cénacles

together was that merry battle spirit we have all come to know and love:

épatez la bourgeoisie

, shock the middle class. With Gautier's

cénacle

especially ⦠with Gautier's own red vests, black scarves, crazy hats, outrageous pronouncements, huge thirsts, and ravenous groin ⦠the modern picture of The Artist began to form: the poor but free spirit, plebeian but aspiring only to be classless, to cut himself forever free from the bonds of the greedy and hypocritical bourgeoisie, to be whatever the fat burghers feared most, to cross the line wherever they drew it, to look at the world in a way they couldn't

see

, to be high, live low, stay young foreverâin short, to be the bohemian.

By 1900 and the era of Picasso, Braque & Co., the modern game of Success in Art was pretty well set. As a painter or sculptor the artist would do work that baffled or subverted the cozy bourgeois vision of reality. As an individualâwell, that was a bit more complex. As a bohemian, the artist had now left the

salons

of the upper classesâbut he had not left their world. For getting away from the bourgeoisie there's nothing like packing up your paints and easel and heading for

Tahiti, or even Brittany, which was Gauguin's first stop. But who else even got as far as Brittany? Nobody. The rest got no farther than the heights of Montmartre and Montparnasse, which are what?âperhaps two miles from the Champs Elysées. Likewise in the United States: believe me, you can get all the tubes of Winsor & Newton paint you want in Cincinnati, but the artists keep migrating to New York all the same ⦠You can see them six days a week ⦠hot off the Carey airport bus, lined up in front of the real-estate office on Broome Street in their identical blue jeans, gum boots, and quilted Long March jackets ⦠looking, of course, for the inevitable Loft â¦

salons

of the upper classesâbut he had not left their world. For getting away from the bourgeoisie there's nothing like packing up your paints and easel and heading for

Tahiti, or even Brittany, which was Gauguin's first stop. But who else even got as far as Brittany? Nobody. The rest got no farther than the heights of Montmartre and Montparnasse, which are what?âperhaps two miles from the Champs Elysées. Likewise in the United States: believe me, you can get all the tubes of Winsor & Newton paint you want in Cincinnati, but the artists keep migrating to New York all the same ⦠You can see them six days a week ⦠hot off the Carey airport bus, lined up in front of the real-estate office on Broome Street in their identical blue jeans, gum boots, and quilted Long March jackets ⦠looking, of course, for the inevitable Loft â¦

No, somehow the artist wanted to remain within walking distance ⦠He took up quarters just around the corner from â¦

le monde

, the social sphere described so well by Balzac, the milieu of those who find it important to be

in fashion

, the orbit of those aristocrats, wealthy bourgeois, publishers, writers, journalists, impresarios, performers, who wish to be “where things happen,” the glamorous but small world of that creation of the nineteenth-century metropolis,

tout le monde

, Everybody, as in “Everybody says” ⦠the smart set, in a phrase ⦠“smart,” with its overtones of cultivation as well as cynicism.

le monde

, the social sphere described so well by Balzac, the milieu of those who find it important to be

in fashion

, the orbit of those aristocrats, wealthy bourgeois, publishers, writers, journalists, impresarios, performers, who wish to be “where things happen,” the glamorous but small world of that creation of the nineteenth-century metropolis,

tout le monde

, Everybody, as in “Everybody says” ⦠the smart set, in a phrase ⦠“smart,” with its overtones of cultivation as well as cynicism.

The ambitious artist, the artist who wanted Success, now had to do a bit of psychological double-tracking. Consciously he had to dedicate himself to the anti-bourgeois values of the

cénacles

of whatever sort, to bohemia, to the Bloomsbury life, the Left Bank life, the Lower Broadway Loft life, to the sacred squalor of it all, to the grim silhouette of the black Reo rig Lower Manhattan truck-route internal-combustion granules that were already standing an eighth of an inch thick on the poisoned roach carcasses atop the electric hot-plate burner by the time you got up for breakfast ⦠Not only that, he had to dedicate himself to the quirky god Avant-Garde. He had to keep one devout eye peeled for the new edge on the blade of the wedge of the head on the latest pick thrust of the newest exploratory probe of this fall's avant-garde Breakthrough of the Century ⦠all this in order to make it, to be noticed, to be counted, within the community of artists themselves. What is more, he had to be

sincere

about it. At the same time he had to keep his other eye cocked to see if anyone in

le monde

was watching.

Have they noticed me yet?

Have they even noticed

the new style

(that me and my friends are working in)? Don't they even

know

about Tensionism (or Slice Art or Niho or Innerism or Dimensional Creamo or whatever)? (Hello, out there!) ⦠because as every artist knew in his heart of hearts, no matter how many times he tried to close his eyes and pretend otherwise

(History! History!âwhere is thy salve!

)

Success was

Success was

real

only when it was success within

le monde.

cénacles

of whatever sort, to bohemia, to the Bloomsbury life, the Left Bank life, the Lower Broadway Loft life, to the sacred squalor of it all, to the grim silhouette of the black Reo rig Lower Manhattan truck-route internal-combustion granules that were already standing an eighth of an inch thick on the poisoned roach carcasses atop the electric hot-plate burner by the time you got up for breakfast ⦠Not only that, he had to dedicate himself to the quirky god Avant-Garde. He had to keep one devout eye peeled for the new edge on the blade of the wedge of the head on the latest pick thrust of the newest exploratory probe of this fall's avant-garde Breakthrough of the Century ⦠all this in order to make it, to be noticed, to be counted, within the community of artists themselves. What is more, he had to be

sincere

about it. At the same time he had to keep his other eye cocked to see if anyone in

le monde

was watching.

Have they noticed me yet?

Have they even noticed

the new style

(that me and my friends are working in)? Don't they even

know

about Tensionism (or Slice Art or Niho or Innerism or Dimensional Creamo or whatever)? (Hello, out there!) ⦠because as every artist knew in his heart of hearts, no matter how many times he tried to close his eyes and pretend otherwise

(History! History!âwhere is thy salve!

)

Success was

Success wasreal

only when it was success within

le monde.

Other books

Susan Carroll by The Painted Veil

In the Bedroom with the Rope: Tied in Knots by McCormick, Jenna

Tumbled Graves by Brenda Chapman

The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath

The Wine-Dark Sea by Patrick O'Brian

A Touch Menacing by Leah Clifford

Amos Gets Famous by Gary Paulsen

The Chain of Chance by Stanislaw Lem

The Dark-Thirty by Patricia McKissack

B0079G5GMK EBOK by Loiske, Jennifer