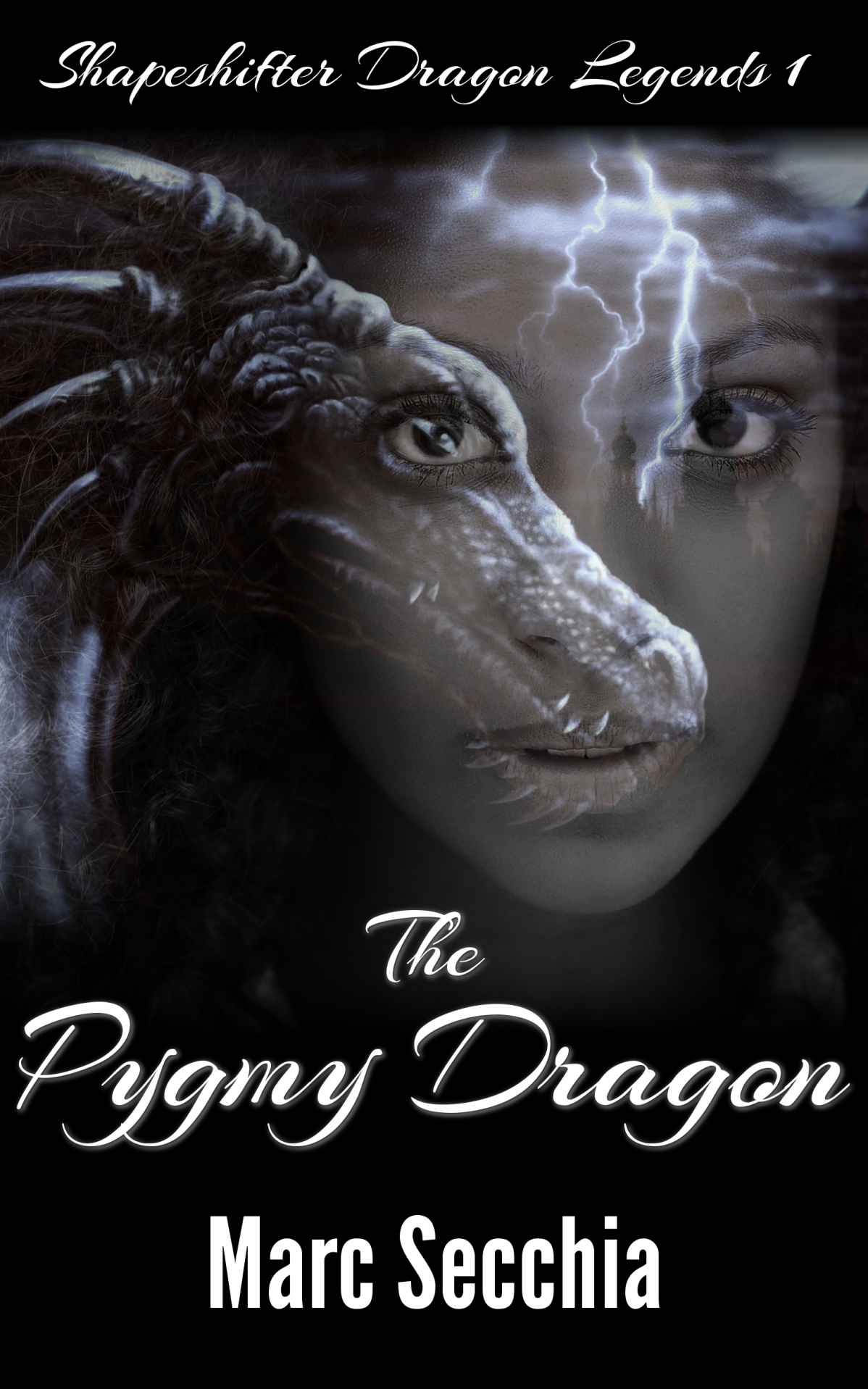

The Pygmy Dragon

Copyright and Cover Art © 2014 Marc Secchia

Cover images © 2014 Shutterstock

Map by Joshua Smolders

Copyright © 2014 Marc Secchia & Joshua Smolders

Y

esterday, a Dragon

kidnapped me from my cage in a zoo.

Islands’ greetings to you. I’m Pip. My friends call me Pipsqueak. I’m a person, like you. Well, I am a little different, but don’t forget, I didn’t belong in a zoo.

You’re a big person. I am a Pygmy. I’m three feet, eleven and a half inches tall. That half-inch is very important to me, because if you and I are going to be friends, then I don’t want to hear any short person jokes from you. Well, I may allow you a few, if you promise to laugh at my big person jokes.

I always thought big people were very strange, especially when they stuck their big person noses against the crysglass window of my cage to gawk at my Oraial Ape friend, Hunagu, and I.

I lived in the zoo for seven summers. That’s a lot of stares.

Big people are hairy and as pale as the grubs we Pygmies eat, not a fine mahogany colour like me. But mostly, they are strange because they would shut a person in a cage. ‘Little savage,’ they’d say. They thought I was not a person.

That hurt.

Big people are not all bad. Early on, I made friends with a man called Balthion, and it’s he who asked me to tell you my story.

We Pygmies usually start our stories by reciting our ancestry. I don’t know my ancestry, because I was captured by a slave trader when I was little. For a Pygmy girl, that’s no bigger than a tadpole. See? I made a little-person joke. Did you laugh? I remember my parents’ names. I struggle to remember their faces. There’s nothing I would want more than to find my tribe and my parents, if they are alive.

I know my name, because I have it tattooed down my left calf.

Fine. You need to take a deep breath. My battle name–my full Pygmy name–is Pip’úrth’l-iòlall-Yò’oótha. I don’t know how to write the bird-trill, so I’ve left it out. I know my name sounds peculiar to your flapping big person ears, with its different clicks, tones and that final bird-trill. You can see why I chose Pip. Why don’t you call me Pip, too? It’s easier. We’re going to be good friends.

By the Islands, you must be wondering about the Dragon.

First, let me tell you a secret. Oraial Apes talk. They talk just like you and me. We Pygmies speak Ancient Southern. You probably speak Island Standard, like all big people. To me it sounds as though you’re gargling a mouthful of mashed-up tinker banana. My best friend Hunagu speaks Ape. You can learn Ape like any other language, as long as you earn an Oraial’s trust. Putting an Ape in a cage is not a way to earn their trust.

Hunagu never belonged in the zoo, either.

Oraials are huge Apes which live in the Crescent Islands. They are about the size of your average big person hut. That’s why our zoo enclosure was so huge, surrounded by thirty-foot walls and armoured crysglass windows for all you big people to stare through. They dug a deep ditch just inside the wall and filled it with spikes so that Hunagu and I could not escape.

None of that mattered when the Dragon arrived. That got you big people quaking in your smelly, furry coats. You must get so many fleas in your coats. Don’t they itch?

I thought Oraials were big until I met a Dragon. I measured myself against his ankle bone. He laughed until his sides hurt.

Here’s another funny thing about big people. You like to write things down. You don’t remember, otherwise. We Pygmies memorise everything. Maybe it’s just me, but I think we have different muscles in our brains. Anyhow, when the Dragon asked me to write my story, I didn’t want to. Dragons are hard to refuse, however. If you’d met one, you’d know what I mean.

So I spoke my story and wrote it down afterward. The result is the scroll you have in your hand.

Wait. Why was a Dragon raiding a zoo for a Pygmy girl?

I asked myself the same question. My friend, the answer is so amazing, so crazily off-the-Island, that you wouldn’t believe me if I told you right now.

Instead, let me tell you my story, my way.

It all started when the slave traders attacked my village.

F

ire rained down

from the night sky. Blazing orange caterpillars crawled amongst the trees. Wet as it was, the jungle foliage caught fire. Two huts burst into flames. Children ran screaming into the dense bushes surrounding the small Pygmy village.

No’otha, one of the older warriors, seized Pip’s arm. “Quick! To the trees. We must fight the sky-beast.”

Pip stared about her, stricken. What was this fire that burned wet wood? Nothing in her eight summers of life had prepared her for this. Even when No’otha’s hard hand smacked her cheek, she barely felt it. The hut! There were three children inside the nursery hut, their faces tiny, dark spots bobbing between the flames engulfing the doorway.

“Arise, Pygmy warrior,” No’otha shouted. “You’ve been Named. Now, fight.”

“I am,” Pip shot back over her shoulder.

She sprinted between the burning huts.

Warriors rushed past her, scattering in all directions as the terrible fire rained down again, screaming ancestor magic-curses at the big people somewhere, unseen, above the village. Pip knew the stories. She had been warned about the big people who came in their sky-beasts–their Dragonships–to raid Pygmy villages. Pygmies hid jewels from their secret mines deep in the jungles, they said. Pygmies made bad slaves. Warriors who stood against the big people were always killed. They did not care for children or old people, but only for cold jewels. They said Pygmies were animals.

Pip had one thought in her mind: to rescue the children. Crimson drops of fire splattered over her as she ran. Pain bit her bare back and legs like a maddened viper. Oil, she realised, from the rank smell. Burning oil. She hurdled a stream of fire and threw herself down next to the nursery hut, around the left side, where she knew the sticks were disintegrating. Pip stabbed her dagger into the rotten wood with all her strength. Twisting, hacking, sawing, she opened a small hole.

“Children. To me.”

They were too frightened to move. Pip forced her shoulders through, ripping the hole wider at the expense of her own skin. The whole front of the hut was ablaze. Acrid smoke filled her lungs. Coughing, she crawled over to the children, who were two or three summers old at most. She spoke softly to them, soothing.

“The flame spirits will bite me,” said the oldest boy.

“Not if we escape through the hole,” said Pip. “I’ll show you how.”

One by one, she helped the children wriggle through to safety. A chunk of burning grass from the hut’s roof fell on her shoulder. The children shrieked, but she brushed off the brand with a forced laugh.

“Come on. We’ll find the cave of warriors. You can hide there.”

Pip made them hold hands. As they stole between the huts, she lifted her short, powerful Pygmy bow from its habitual place, slung over her shoulder. She touched her quiver of arrows and said a quick prayer to the guardian spirits. Her sharp ears caught the sounds of Pygmy warriors scrambling up into the trees. They would fight the big people from the trees and branches of their jungle home. But Pip winced as she saw liquid fire running down one of the massive trunks, igniting the purple sha’ork vines which turned the jungle giants into dark, leafy pillars. Dark Pygmy warriors fell to the ground. Suddenly, flame roared up the tree-trunk. She had to close her ears. She could not bear the screams and cries rising on all sides.

Instinctively, she scooped up the smallest child and leaped across a patch of burning leaves. Her feet raced over the paths she knew so well, down the hidden gully beside the village toward the cave of warriors, where the Pygmies honoured their dead.

The cave would be full tonight.

Pip had been Named just a week before. She was proud of her name-tattoo, painstakingly marked in runic script down the outside of her left calf. Her leg throbbed as she hustled her three charges along. She had not made a sound during the painful tattooing process. That would have been shameful. Pip’úrth’l-iòlall-Yò’oótha, her tattoo said, in neat blue letters from her knee to her ankle bone. Her battle name. The Pygmy Seer had taken it from one of the ancient tales.

Pygmies believed that a name fixed a person’s destiny. When she was sixteen summers of age–the number which signified four sacred fours–the Seer would reveal her name’s true meaning at the ceremony of Second Naming.

Pip kept glancing over her shoulder. The big people were coming, she sensed.

Once she had shown the children safely into the cave, Pip raced back along the trail to the village. Branches slapped her face. Agile as a monkey, she hurled herself over several tree roots which were taller than her. She had to help the other warriors.

Pip skidded to a halt just within the perimeter fence of the village. Flames leaped and danced all around her. A dozen or so blazing Pygmy huts shot sparks up into the massive boughs overhanging the village. Many of those were burning, too. The oil had seen to that.

Through holes in the foliage created by the leaping fires, Pip saw a huge, oblong shape hanging over the village. That had to be a Dragonship. Somehow, the big people had brought it in low, right among the immense jungle giants. A couple of dark shadows clambered up the Dragonship’s sack–Pygmy warriors, attacking the beast with their curved daggers.

She filled her nostrils with the scent of burning.

There. Pip saw a group of strange, metallic creatures approaching her through the trees. They wore helmets and armour, and great flowing robes the colour of fresh blood. She had never seen creatures like these. She imagined their steps made the entire Island tremble. Were they men? Pip swallowed hard. A warrior must stand her ground. Soberly, she selected an arrow from her quiver. Let these strange creatures know that a Pygmy warrior would not flee.

Pip raised her bow and sighted her first shot.

Breathe. Slowly in, even more slowly out. Focus. Her shoulders relaxed. Pip’s lips breathed an ancient magic word.

Fly true.

Narrowing her eyes on the target, the biggest of the creatures in the lead of that group, she released her shot. Perfect. Right in the belly.

He kept on coming.

The Seer told stories about big people with metal skin which could not be pierced by arrows. Pip’s hands shook as she sighted again. The throat, she thought. A difficult shot, but maybe the throat or the face would be vulnerable. She missed. Hissing now in anger, Pip fired a third time. Her target clutched its throat and fell to the ground, writhing.

Pip had killed animals many times. But now she had shot a person–a big person, not a creature, because she could hear his strangled cries over the roar of flames all around her. She fell to her knees, vomiting. Then she wiped her mouth and drew another arrow.

“Spirits have mercy,” she whispered.

She slipped forward as if trapped in a nightmare. Her hands moved, aimed and released without need for thought. Pip saw two, three more men fall, two struck in the throat and one in the eye. The others scattered for cover. Maybe they thought they faced a dozen warriors.

Instead, only a young Pygmy warrior confronted them. The flames flickered hungrily around the edges of her vision. Her resolve hardened. These men were killers. They had destroyed her village. They had slaughtered her friends and neighbours. Pip shot a big person who was trying to hide behind No’otha’s prone body. He was clumsier than a wild pig tied for the spit. Whirling on her heel, she shot another in the hand. Arrows swished through the air toward her. She dived forward. Rolling smoothly up onto one knee, Pip put an arrow into another face peering at her from behind old Sith’jó’s carving stone, where he used to love to sit and make arrows or bowls for eating. Strangely, she did not fear being hit. She feared nothing.

The grey and brown eyes watching her widened in disbelief. The big people made the noises they called speech. She understood a couple of words, as the Seer had been teaching the warriors a few words of Island Standard to use while trading python meat or arrows for necessities for the village. She understood ‘catch her’, and ‘Pygmy’, but little else.

Pip swayed away from a big person arrow flying toward her with the speed of a plump wood-pigeon. She was a hawk. She shifted her position again, as lithely as a dancer at one of the tribe’s many celebrations, and surprised one of the armoured big people as he popped his head out from behind a hut. He was so close, she gagged at his rancid breath. As the mouth snarled at her, Pip fired an arrow up into it.

The man fell with a terrible, gargling cry. Pip saw that he had a friend right behind him. Metal gleamed in the firelight. Pain lanced into her flank. His blade had sliced into the flesh of her lower right ribs. Pip staggered. Her fingers came away bright with blood. A boot kicked her legs out from beneath her. The breath whooshed out of her lungs as she fell heavily on her side, as though she had been struck by a falling log.

Next she knew, two of the armoured warriors loomed over her. Gripping one of her poisoned arrows in her fingers, Pip stabbed at a leg. She managed a shallow cut before a warrior’s boot smashed down on her arm and pinned her like that. She distinctly heard a bone snap. Her scream stopped in her throat as she saw a cudgel blur toward her head.

Darkness exploded between her eyes. She remembered nothing more.