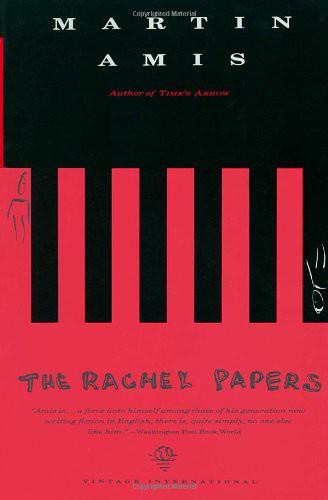

The Rachel Papers

Authors: Martin Amis

The Rachel Papers

Martin Amis

Vintage (1992)

Rating: ★★★☆☆

Tags: Fiction, Literary

Fictionttt Literaryttt

In his uproarious first novel Martin Amis, author of the bestselling London Fields, gave us one of the most noxiously believable -- and curiously touching -- adolescents ever to sniffle and lust his way through the pages of contemporary fiction. On the brink of twenty, Charles High-way preps desultorily for Oxford, cheerfully loathes his father, and meticulously plots the seduction of a girl named Rachel -- a girl who sorely tests the mettle of his cynicism when he finds himself falling in love with her.

Review

Amis's vision of adolescence is an unvarnished, terrifying and hilarious one."-- New Yorker

"A truly sexy and funny book...a delight...the best teenage sex novel since Goodbye Columbus." -- New York

"Amis is a born comic novelist, in the tradition that ranges from Dickens to Waugh...He can find laughter in catastrophe and knows that morality shifts sneakily between absolutes and ambiguity...Amis's mercurial style...can rise to Joycean brilliance."

From the Inside Flap

In his uproarious first novel Martin Amis, author of the bestselling London Fields, gave us one of the most noxiously believable -- and curiously touching -- adolescents ever to sniffle and lust his way through the pages of contemporary fiction. On the brink of twenty, Charles High-way preps desultorily for Oxford, cheerfully loathes his father, and meticulously plots the seduction of a girl named Rachel -- a girl who sorely tests the mettle of his cynicism when he finds himself falling in love with her.

Martin Amis

Martin Amis is well known on both sides of the Atlantic as the author of

Time's Arrow, London Fields, Einstein's Monsters, Money, Other People, Success,

and

Dead Babies.

He has contributed to such periodicals as

Vanity Fair, The Observer,

and

The New Statesman.

He lives in London. His most recent novel is

The Information.

Copyright © 1973 by Martin Amis

Author photograph © Jerry Bauer

for Gully

Quarter to eight: the Costa Brava

Thirty-five minutes past eight: The Rachel Papers, volume one

Twenty-five of eleven: the Low

Eleven ten: The Rachel Papers, volume two

Twenty past: 'Celia shits' (the Dean of St Patrick's)

The Rachel Papers

Seven o'clock: Oxford

My name is Charles Highway, though you wouldn't think it to look at me. It's such a rangy, well-travelled, big-cocked name and, to look at, I am none of these. I wear glasses for a start, have done since I was nine. And my medium-length, arseless waistless figure, corrugated ribcage and bandy legs gang up to dispel any hint of aplomb. (On no account, by the way, should this particular model be confused with the springy frames so popular among my contemporaries. They're quite different. I remember I used to have to fold the bands of my trousers almost double, and bulk out the seats with shirts intended for grown men. I dress more thoughtfully now, though, not so much with taste as with insight.) But I

have

got one of those fashionable reedy voices, the ones with the habitual ironic twang, excellent for the promotion of oldster unease. And I imagine there's something oddly daunting about my face, too. It's angular, yet delicate; thin long nose, wide thin mouth -and the eyes: richly lashed, dark ochre with a twinkle of singed auburn ... ah, how inadequate these words seem.

The main thing about me, however, is that I am nineteen years of age, and twenty tomorrow.

Twenty, of course, is the real turning-point. Sixteen, eighteen, twenty-one: these are arbitrary milestones, enabling you only to get arrested for H.P.-payment evasion, get married, buggered, executed, and so on: external things. - Naturally, one avoids like the plague such mischievous doctrines as 'you're as young as you feel,' which have doubtless resulted in so many trim fifty-year-olds flopping down dead in their tracksuits, haggard hippies checking out on overdoses, precarious queers getting their caps and crowns stomped in by bestial hitch-hikers. Twenty may not be the start of maturity but, in all conscience, it's the end of youth.

To achieve, at once, dramatic edge and thematic symmetry I elect to place my time of birth on the stroke of midnight. In fact, mother's was a prolix and generally rather inelegant parturition; she went into labour about now (i.e., about seven p.m., December 5th, twenty years ago), not to come out of it again until past twelve, the result being a moist four-pound waif that had to be taken to hospital for a fortnight's priming. My father had intended - Christ knows why - to watch the whole thing, but got browned off after a couple of hours. I have long been sure that there is great significance in this anecdote, although I have never been able to track it down. Perhaps I'll find the answer at the moment at which, two decades earlier, I first sniffed the air.

I confess that I've been looking forward to tonight for months. I thought when Rachel turned up about half an hour ago that she was going to ruin it all, but she left in time. I need to make the transition decorously, officially, and to re-experience the tail-end of my youth. Because something has definitely happened to me, and I'm very keen to know what it is. So: if I run through, let's say, the last three months, and if I try to sort out all my precocity and childishness, my sixth-form cleverness and fifth-form nastiness, all the self-consciousness and self-disgust and self-infatuation and self- ... you name it, perhaps I'll be able to locate my

hamartia

and see what kind of grownup I shall make. Or not, as the case may be. Anyway, it ought to be good fun.

Now it's - let me see - just gone seven. Five hours of teenage to go. Five hours; then I wander into that noisome Brob-dingnagian world the child sees as adulthood.

I snap open my dinky black suitcase and up-end it on the bed; folders, note-pads, files, bulging manilla envelopes, wads of paper trussed in string, letters, carbons, diaries, the marginalia of my youth, cover the patchwork quilt. I jostle the papers into makeshift stacks. Ought they to be arranged chronologically, by subject, or by theme? Patently, some rigorous clerking will have to be done tonight. At random I pick up a diary, cross the room, and lean against the bookcase, which creaks. I sip my wine and turn the page.

The second weekend of September. At that point I had only a couple more days of home to endure before going down to London. It was on the Thursday that my father, drinking spirits for the first time in years, had wondered why I didn't 'have a crack' at getting into Oxford and I had nodded back at him, wondering why not, too. I was going to have a year off before university anyway. My English master had always impressed upon me how fucking clever I was. I didn't particularly want to go anywhere else. It seemed logical.

Mother got all bustly the next morning (fixing everything up) but came on vague and spiritual over lunch and resolved to take an afternoon nap. When I asked her what there was left to do she free-associated, until it became clear, as a jigsaw becomes clear, that she had succeeded only in telling my sister that I would be coming to stay and also (one assumes) giving her the usual half-hour rundown on the perils of the late menopause, and other such female smut.

'So,' I said, 'I ring the Oxford Admissions and UCCA

and

the Tutors.'

Mother left the kitchen with one hand flat on her forehead and the other suspended in the air behind her. 'Yes, dear,' she called.

It took about an hour because I am surprisingly ineffective on the telephone. I spoke to key tarts in the University Administration complex and finally got on to the Tutors, where a shifty dotard told me that it wasn't for him personally to say but he was fairly sure they would be able to fit me in. I realized then that I was half hoping for some insurmountable snag, like entrance dates. Yet it all seemed to be going forward.

I didn't know why I hoped this. Oxford meant more work, of course, but that was no problem. It meant more exams, but, again, I rather like having definite horizons, foreseeable crunches, to focus my anxieties on. Perhaps, as a person inclined to think structurally about his life, I had planned the next few months with my twentieth birthday in mind. There were several teenage things still to be done: get a job, preferably a menial, egalitarian one; have a first love, or at least sleep with an Older Woman; write a few more callow, brittle poems, thus completing my 'Adolescent Monologue' sequence; and, well, just marshal my childhood.

There is a less precious explanation. My family lives near Oxford, so if I went there I should have to spend more time at home. Furthermore, I dislike the town. Sorry: too many butterfly trendies, upper-class cunts, regional yobs with faces like gravy dinners. And the streets there are so affectedly narrow.

It is a Highway tradition that on Sunday afternoons, between the hours of four and five, any family representative can approach its senior member in what he calls his 'study' and there discuss matters, or crave assistance, or air grievances. One simply knocks and enters.

A small and rather hunted-looking figure now, my father said hello and asked what he could do for me, leaning over to empty the two-pint jug of real orange-juice, his daily ration, which he usually tucked away before eleven a.m. His eyes bulged warily over the discoloured glass as I told him that everything was fixed. There was a pause, and it occurred to me that he had forgotten the whole thing. But he soon roused himself. His hostile levity went like this :

'Super. I'm driving down tomorrow morning, I suppose I can take you along without too much trouble, so long as you don't bring all your worldly goods with you, that is. And don't worry yourself about Oxford. It's only the icing on the cake.'