The Raw Shark Texts (7 page)

You will notice that the letters produced still appear to be random at this point. They don’t make any sense. That is because there is still more to do.

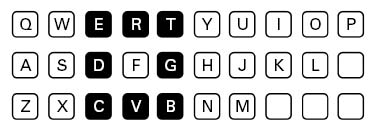

The second part of the code uses the layout of a computer or typewriter keyboard, as below (with rows two and three slightly realigned to make a grid):

Each letter from the translated Morse code sequence is applied to the grid:

The final, correctly decoded letter will always be one of those adjacent to the Morse code letter. For example, if you translate an ‘F’ from the Morse code, the actual letter you are looking for will be one of the eight adjacent to ‘F’ on the QWERTY layout:

The translation letters also ‘rollaround’. This is a way of saying if a Morse code letter touches the edge of the board, as B does

the possible translation letters will not only include V, F, G, H and N, but also R, T and Y, as the three unavailable bottom spaces are rolled up to the top.

This rollaround is applied to all edge-of-grid letters, as shown here:

As you are probably noticing, the code is not very specific. When translated from Morse, each letter has eight possible solutions. Only one of these will be the correct letter. This means clean text cannot be constructed at the level of the individual letter. Possible translations must be constructed at word level, re-evaluated at sentence level and refined at paragraph level. It makes the process very

time-consuming. It will take a long time. I think I built ambiguity into the encryption as added camouflage against the word shark. Did I? Well. It seems to serve no other purpose. It’s raining here in the past. I hope the weather there in the future is better.

Regret and hope,

E

(Received: 29th April)

Letter #205

Dear Eric,

Six months. Are you still with me? A sort of half birthday if you are, I’m sorry. I’m sorry you are so alone.

Now, here is what this letter is about:

There is a story. There is a story I’ve been avoiding. It’s the story about why all this is happening. Why the Ludovician is hunting you. It’s all my fault, Eric.

Stories. There used to be more stories, records of other things, other fragments I’d written down or encoded. I can remember some of their names. Once, there was The Dust Fragment and The Shadow Fragment and The Envelope Fragment, as well as The Light Bulb Fragment which you have. But it’s dangerous here in the past where I am and things get muddled or lost or destroyed. I’m trying, I’m trying to save as much as I can but those fragments have all gone and I can’t remember what they said.

There once was a fragment called The Aquarium Fragment. I have a single piece of text left from The Aquarium Fragment. It is part of the story of why all this is happening. I will try to tell the story and slot this little bit of fragment in the right place.

This is how the story goes:

To try to change what happened to Clio, I went looking for a man called Dr Trey Fidorous. I don’t know, I don’t remember what I thought this Dr Trey Fidorous could do, but I devoted myself to finding him. He was a writer, an academic, I think. I looked for him first in his dense and complex papers, all filed and forgotten in university basement stacks. From them, I found his rolling pencil footnotes in a set of old encyclopaedias in a library in Hull. They led me to flyposted text-swarmed poster sheets in Leeds, and from Leeds, on to series of essays written in black marker on the tiles of underpasses in Sheffield. The underpass essays led me to a suite of chalked texts on the walls of an old tower block in Manchester.

I remember this part, this route so clearly because I repeat it to myself every

day: ‘The dictionary in Hull, the posters in Leeds, the underpasses in Sheffield, the tower block in Manchester.’ And then there’s a last stop on this route, the place I finally found Dr Trey Fidorous: I found him sick in a closed-up doorway in Blackpool. Something had happened to him. I can’t remember what it was.

Hull. Leeds. Sheffield. Manchester. Blackpool.

Hull. Leeds. Sheffield. Manchester. Blackpool.

What happened next is I went with Fidorous down into the empty, abandoned areas in the world which are sometimes called un-space (I will write you a letter about un-space another time) and I studied with him down there. I learned things, the things I am teaching you about survival and other things too, things he wanted me to know and things he didn’t want me to know, that I shouldn’t have known. I thought I could save her, Eric. I had so many ideas. The details have all gone.

Somewhere in un-space, there was a hole. A deep black hole, a lift shaft. I’d been looking for that hole, for a way to get down it, for so long. It’s patchy, sketchy. Mostly all I have are the feelings left behind, emotion shadows where the facts should be. I do know that I left Fidorous to go looking for that hole and that I hired someone to help me find it, someone from what is called the Un-Space Exploration Committee (I will write you a letter about the Un-Space Exploration Committee too) but the details of that part, the hows and the whys, when I try to think about them they all come apart like rotten old cloth.

I did find the hole.

Down at the bottom there was a place filled with rows and rows of stinking neglected fish tanks with sick, dead and dying fish; a horrible abandoned aquarium. In the heart of the place, that’s where I found the Ludovician. It was younger then, much smaller but still very dangerous. And I let it out of its conceptual loop prison, Eric. I did it. It was me. I gave myself to the thought shark and it ate and ate, growing bigger and bigger and now it’s an adult and there’s no stopping it. I killed myself and I’ve probably killed you too. Why did I do it? Why would I do that?

I think I thought I could save her.

I was so stupid. I was so stupid and now everything’s all gone.

This is the only piece of The Aquarium Fragment I have left, the end of the story. As always, some parts, some meanings, are missing:

]

stepped inside the tank-circle.[missing text]

suddenly had a very clear memory of my Granddad, tall and Roman-nosed with silver Brylcreemed hair, hanging wallpaper on old, dark, paint-splattered stepladders. I thought about how since his death my Granddad had become more a collection of scenes than a real man to me, how I could recall him being kind, angry, serious and joking but how the edges of these memory events didn’t quite fit together and left me with a sort of schizophrenic collage rather than the real, rounded-out man I must have known as a child.My senses, trying to catch my attention in all this, suddenly broke through to the surface and I came back into the present. A horrific clarity came into the world, a sense of all things being exactly what

[missing text]

with relevance, obviousness and a bright

[missing text].

Without me telling it to, my mind switched itself back to the image of my Granddad up the ladder. And then I saw it, partly with my eyes, or with my mind’s eye. And partly heard, remembered as sounds and words in shape form. Concepts, ideas, glimpses of other lives or writings or feelings. And living, the thing obviously alive and with will and movement. Coming oddly

[missing text]

light links in my memory, swimming hard upstream against the panicking fast flow of my thoughts. The Ludovician, into my life in every way possible.

I did it, Eric. I let it out. I’m responsible.

I really am so sorry.

Regret and hope,

Eric

(Received: 1st May)

Letter #206

Dear Eric,

Q) What is un-space?

A) It is the labelless car parks, crawl tunnels, disused attics and cellars, bunkers, maintenance corridors, derelict industrial estates, boarded-up houses, smashed-windowed condemned factories, offlined power plants, underground facilities, storerooms, abandoned hospitals, fire escapes, rooftops, vaults, crumbling churches with dangerous spires, gutted mills, Victorian sewers, dark tunnels, passageways, ventilation systems, stairwells, lifts, the dingy winding corridors behind shop changing rooms, the pockets of no-name-place under manhole covers and behind the overgrow of railway sidings.

Q) Who are the Un-Space Exploration Committee?