The Real Life Downton Abbey (9 page)

Read The Real Life Downton Abbey Online

Authors: Jacky Hyams

Each housemaid is allocated a set number of responsibilities, starting work at between 5.30 and 6am. Their first task is to make tea for the lady’s maid and housekeeper and by 6.30am they are busy lighting fires, cleaning all the public rooms of the house, making beds, sweeping, dusting and cleaning the bedrooms, the bathrooms and the other rooms, scrubbing floors, sweeping ashes, polishing grates, windows and ledges, cleaning the marble floors and all the furniture, brushing carpets, beating rugs, carrying coal to the fireplaces and making sure the fires are stoked properly.

In some cases, one housemaid works only for the upper staff, another is allocated a specific room to clean all the time. Because there’s great emphasis on specific rooms for specific purposes, a housemaid can be allocated a medal room, with rows of steel cases containing medals – which must be polished (with emery paper) every single day. Or when there’s a house party, it’s often the housemaid who has to wash the loose change the men in the party have emptied from their pockets and left out the previous night, so that a valet may return the shining coins to their owners later on.

A very hard-working housemaid can work her way up to a housekeeper’s role. If she can handle the relentless monotony – and the sheer physical slog of doing nothing but clean for 14–16 hours a day.

The scullery maid is consigned to the kitchen only, the

lowest-ranking

female servant below the kitchen maids and the cook.

Her day begins around 4am because she must clean the grates and lay out the fire to heat the water if the cooking is being done on a coal-fired range. She must also dust the kitchen and scullery area before Cook starts work. Then it’s back to the kitchen, for an endless round of washing up all the pots, pans, dishes, plates and cutlery for all the meals of the day. In between washing-up she must set the table for the servants’ meals, wash the vegetables, peel potatoes, rub blocks of cooking salt through a sieve – and constantly make sure the big area in and around the kitchen is as clean as possible. The washing-up is endless – each copper pan used for cooking has to be thoroughly cleaned after use with a mixture of sand, salt, flour and vinegar.

Ignored by the household, often ridiculed by the upper servants and at the very bottom of the pecking order, the scullery maid has a very raw deal indeed. As raw as the skin on her hands.

WHAT’S IN A NAME?The lower servants deeply resent the uppers and the marked distinction in their status. So they have a nickname for them. They call them ‘Pugs’ (in honour of the upturned nose and downturned mouth of the pug dog, so popular at the time). So the housekeeper’s sitting room, her powerbase, is dubbed ‘The Pug’s Parlour’ – because after meals, the uppers follow each other, in strict order of rank, down the corridor into the housekeeper’s room to eat the final course of pudding or cheese.

NO CHANCE OF A CUDDLE, THEN?Although the butler is always addressed by the family by his surname – Mr Carson in

Downton Abbey

– the toffs always address their footmen by their first names. Yet the names they use are unlikely to be their footmen’s real names. The names Charles, John or James are used to address these servants, regardless of how they were christened. Better than ‘hey you’. But another way of reminding them that they are mere underlings.

THE LIVE-IN LAUNDRYThe toffs insist on segregating the sexes of their servants at all times, even when daily cleaning duties are involved. For instance, a housemaid allocated a specific bedroom to clean must attend to the fireplaces, windows and ledges, sweep the floors and the carpets – and then wait for the dust to settle. Only then can she leave the room. And only then can the footman come in to do his job of polishing the furniture. They are not allowed to be cleaning the same room together – especially a bedroom!

By 1911 laundry maids are on the decline because some families now send all laundry out to big commercial laundries. (Some country families send their laundry off to a preferred top people’s laundry in London, because it can be dispatched and returned by rail.) But other country-house owners more resistant to change prefer to continue to launder at home, some with a new, slightly different system: replacing the old in-house laundry with one attached to a small four-bedroom cottage some distance away from the house on the estate.

THE BELLS, THE BELLSThe cottage laundry uses traditional laundry methods – there’s still no electricity – and three or four laundry maids live in the cottage, earning £1 a week in board wages, which goes into a kitty and is given to the head laundress, who shares the profit among the girls. Long hours and a hard slog for them – but a slightly more flexible system. And a fraction more independence.

The system of summoning servants by wire bell-pull systems installed in the house was originally established in the eighteenth century. Yet many aristocratic households were still using the bell system well into the twentieth century.

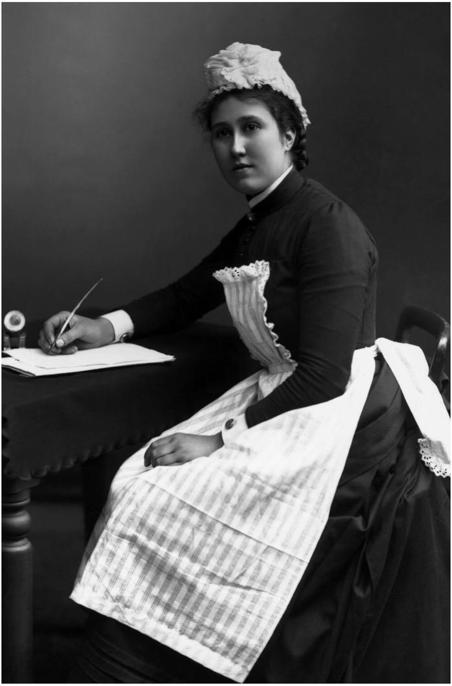

A housemaid circa 1900

Chapter 4

‘

T

he Rules’ involve everyone working in the big country house. And they cover virtually everything to do with daily life – communication, cleaning, eating and drinking; only sleeping is a rule-free zone – and for the servants, there’s precious little of that, anyway. Rules vary from house to house, but they are very much fixed conditions of service and there isn’t much flexibility.

Family members, of course, have different rules involving their own world – but they also have a specific set of rules around their treatment of their servants.

Here’s a summary of the kind of rules they were expected to follow:

HE

M

ASTER-

S

ERVANT

R

ELATIONSHIP

R

ULES

- All family members must maintain appropriate relationships with the staff. As upper servants work directly to the family, a trusting and respectful relationship should be established.

- Footmen are a proclamation of wealth and prestige. They are representatives of the household and family and, as such, it is advantageous that a good relationship is developed. However, as lower servants they do not expect to be addressed outside the receipt of instructions.

- While the housemaids will clean the house during the day, they should make every care and attention never to be observed doing their duties. If, by chance they do meet their employer, they ‘give way’ to the employer by standing still and averting their gaze, whilst the employer walks past, leaving them unnoticed. By not acknowledging them, the employer spares them the shame of explaining their presence.

- The mode of address to the staff has to be correct and proper. There is no ‘Hey, you’ or ‘Excuse me’. It has to be precisely the right title, according to the status of the servant. Or, in some cases, nothing at all because the employer does not wish, at any time, to be reminded of the physical presence of the lower servants.

OW TO ADDRESS A SERVANT

- The Butler should be addressed courteously by his surname.

- The Housekeeper should be given the title of ‘Mrs’ (or Missus).

- The Chef de Cuisine should be addressed as such – or by the title ‘Monsieur’.

- The Lady’s Maid should be given the title of ‘Miss’ regardless of whether she is single or married. It is acceptable for the Mistress to address her by her Christian name.

- A Tutor should be addressed by the title of ‘Mister’.

- A Governess should be addressed by the title of ‘Miss’.

- It is the custom in old houses that, when entering into new service, lower servants adopt new names given them by their masters. With this tradition certain members of staff are renamed. Common names for matching footmen are James and John. Emma is popular for housemaids.

- It is not expected that the employer takes the trouble to remember the names of all staff. Indeed, to avoid conversation with them, lower servants will endeavour to make themselves invisible. As such, they should not be acknowledged.

ERVANT

R

ULES

Written rules for the servants are equally draconian. Each country house has their own set of written rules for the servants, organised by the butler and housekeeper. Curiously enough, while the penalties for breaking these rules are often harsh, there are times when the master or mistress of the house might be a tad more sympathetic or forgiving of a breach of the rules than the butler and/or housekeeper. This is probably because they’ve slogged their way up the servant hierarchy over a period of many years and stick to the old ‘I came up the hard way, so must you’ maxim, while the employer, waited on at all times, has no real sense of the reality of the servant’s lot and can, depending on their personality, give in to a kinder, more sympathetic gesture.

Here’s a sample of Servant Rules (taken from the archives of Hinchingbrooke House, a country house in Cambridgeshire):

- Your voice must never be heard by the ladies and gentlemen of the household, unless they have spoken directly to you a question or statement which requires a response. At which time, speak as little as possible.

- Always ‘give room’ that is, if you encounter one of your employers in the house or betters on the stairs you are to make yourself as invisible as possible, turning yourself toward the wall and averting your eyes.

- When being spoken to, stand still, keeping your hands quiet. And always look at the person speaking to you.

- Never begin to talk to ladies and gentlemen unless to deliver a message or to ask a necessary question and then, do it in as few words as possible.

- Except in reply to a salutation offered, never say ‘good morning’ or ‘good night’ to your employer. Or offer any opinion to your employer.

- Whenever possible, items that have been dropped, such as spectacles or handkerchiefs, and other small items, should be returned to their owners on a salver [a dish].

- Never talk to another servant, or person of your own rank, or to a child, in the presence of your mistress unless from necessity. Then do it as shortly as possible and in a low voice.

- Never call from one room to another.

- Always respond when you have received an order and always use the proper address: ‘Sir’, ‘Ma’am’ ‘Miss’ or ‘Mrs’ as the case may be.

- Always keep outer doors fastened. Only the Butler may answer the bell. When he is indispensably engaged, the assistant, by his authority, takes his place.

- Every servant must be punctual at meal times.

- No servant is to take any knives or forks or other article, nor on any account to remove any provisions, nor ale or beer, out of the Hall.

- No gambling, or Oaths, or abusive language are allowed.

- The female staff are forbidden from smoking.

- No servant is to receive any Visitor, Friend or Relative into the house, nor shall you introduce any person into the Servant’s Hall without the consent of the Butler or Housekeeper.

- Followers are strictly forbidden. Any maid found fraternising with a member of the opposite sex will be dismissed without a hearing.

- No tradesmen or any other business having business in the house are to be admitted except between the hours of 9am and 3pm. In all cases the Butler or Chef must be satisfied that the persons he admits have business there.

- The Hall door is to be finally closed at Half-past Ten o’clock every night after which time the lights are out and the doors secured.

- The servants’ hall is to be cleared and closed at Half-past Ten o’clock, except when visitors and their servants are staying in the house.

- No credit upon any consideration to be given to any person residing in the house or otherwise for Stamps, Postal Orders, etc.

- Expect that any breakages or damage in the house will be deducted from wages.

Not much of a life, is it? No swearing, smoking – or a hint of sex. In fact, the toffs are firmly convinced that the best way to keep the servants in line is to keep them working all the time – because the general belief is that if they are given time to themselves, they will indulge in the three Great No-Nos:

- Sex

- Alcohol

- Gambling