The Red and the White: A Family Saga of the American West (2 page)

Read The Red and the White: A Family Saga of the American West Online

Authors: Andrew R. Graybill

Tags: #History, #Native American, #United States, #19th Century

Helen’s journey proved far more arduous than that of her brother. After her father’s murder, she left Montana to join Malcolm’s family in the Midwest. She then enjoyed a brief but highly acclaimed stage career in New York and Europe, where she starred in several productions with the famous French actress Sarah Bernhardt. Drawn ineluctably back to her native land, Helen returned to Montana and served for eight years as the superintendent of schools for Lewis and Clark County; that made her the first woman to hold elective office in the history of the territory. In 1890 she assumed an even more unusual post for a woman, accepting a position as one of the nation’s first female allotment agents. In this capacity she moved to Indian Territory and participated in the breakup of the Ponca and the Otoe Reservations, among others. And yet in the end, despite having spent most of her adult life in the white world and assisting in the dispossession of indigenous peoples, Helen selected her own allotment on the Blackfeet Reservation, where she lived with her brother Horace until her death in 1923.

The book concludes with the story of Horace’s son, John. Born in 1881, twelve years after the murder of a grandfather he never knew, John contracted scarlet fever as an infant and was rendered deaf and mute. In spite of his deafness, he became a renowned sculptor of western wildlife; he captured the attention of Montana luminaries like the famed cowboy artist Charlie Russell and attracted such deep-pocketed patrons as John D. Rockefeller Jr. Yet for all his acclaim and widespread acceptance by non-Indians, Clarke rarely left the reservation, choosing instead to live there with his wife and adopted daughter, both of whom were white. In 2003, more than three decades after his death, Clarke was inducted into the Gallery of Outstanding Montanans, a hall of fame celebrating notable residents of the Treasure State.

In the end, I came to appreciate my great fortune in stumbling upon the history of the Clarke family, which offers keen insight into the lives of people who were both red and white, and thus contemptuously dismissed in their own time and often since as “half-breeds.” If their experiences were typical in many ways of mixed-blood families in the Rocky Mountain West of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, their lives were nevertheless extraordinary, and the Clarkes are still well known throughout Big Sky Country, with their names literally etched into the geography of northern Montana. They are remembered, too, for their tragic association with the darkest day in Piegan history. This book, then, is the story of their journey through the complex landscape of race in America, with particular attention to what they gained—and what they lost, irretrievably—along the way.

*

The spelling of the family surname was wildly inconsistent throughout the nineteenth century, alternating between “Clark” and “Clarke” until the latter became the widely accepted version.

S

ometime in 1844 a young Piegan woman married a white trader employed by the American Fur Company (AFC). The bride was about nineteen, slightly beyond the typical age of first marriage for women of her tribe but nearly a decade younger than her new husband. Little else about the wedding is known for certain, and even the date is merely an educated guess handed down through generations.

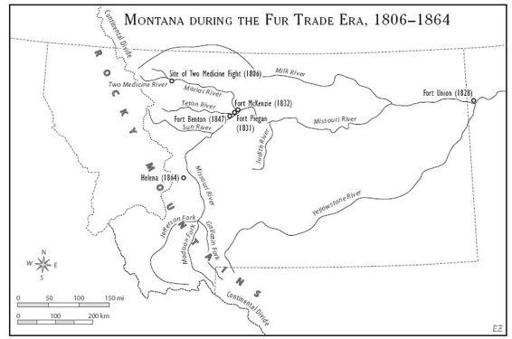

The couple probably wed at Fort McKenzie, a key AFC post in what is now north-central Montana. Located on the north bank of the Missouri River—the broad riparian thoroughfare that threads across the upper reaches of the Great Plains before tumbling into the Mississippi—the small stockade was dwarfed by steep bluffs that thrust upward from the south bank and ended at the water’s edge. If the scenery was dramatic, however, the ceremony was much less so, consisting perhaps of a simple exchange of horses between the groom and the bride’s family.

The woman’s name was Coth-co-co-na, meaning “Cutting Off Head Woman,” a moniker conjuring up her indispensable role in dressing animal skins. At the time of her wedding, the fur trade was the dominant economic pursuit of her people, the Piegans, one of the three groups of the so-called Blackfoot Confederacy. Her father, Under Bull, was a reputable warrior, and it was he who selected her husband. He chose well, for Malcolm Clarke, though he had been on the Upper Missouri for only a short time, was already one of the AFC’s most successful traders, endowed with irresistible charm and ruthless business acumen. Clarke was also remarkably handsome: just shy of six feet, with brown eyes, soft auburn hair, and a dark beard.

By most objective measures, their union appears unlikely, even extraordinary, given the vast chasm between husband and wife in terms of race, language, custom, and experience. After all, Coth-co-co-na had lived her entire life within the shadows cast by the Rocky Mountains, whereas Malcolm Clarke was born in Indiana and raised in Ohio, and he had spent two years at the U.S. Military Academy before coming west in his midtwenties. Moreover, the first meeting between their peoples four decades earlier had ended in a spasm of violence that left two Piegans dead and their tribesmen bearing a powerful grudge against the white invaders.

And yet, despite the seeming improbability of a partnership like theirs, such marriages were in fact quite common throughout fur country and had occurred wherever the trade in animal skins flourished in North America, dating back as far as the seventeenth century. Nearly all of Malcolm Clarke’s AFC associates had Indian wives, a circumstance that provoked condemnation from white Americans in the East both for the transgression of racial boundaries and for the sense that these nuptials—as the gift exchanges that accompanied them suggested—were, in effect, business transactions meant only to facilitate the fur trade, devoid of love and commitment and lacking religious consecration. Although the economic benefits were undeniable, especially for the groom and his in-laws, many of these unions were built upon genuine affection. So it was with Coth-co-co-na and Malcolm Clarke.

In order to understand their marriage and the world they made, a world that, according to a family friend, “mingles the best of the white race and the red,” one must start with the broader history of the period, beginning on an unseasonably warm day in New Orleans some forty years before that humble wedding ceremony at Fort McKenzie.

One Land, Two Worlds

Though it was nearly Christmas, 20 December 1803 was a beautiful day in New Orleans, with ample sunshine and moderate temperatures more typical of late spring than the onset of winter. The pleasant weather, however, did not lift the spirits of Pierre Clément de Laussat, the French governor of Louisiana. His duty that morning was the sad one of transferring control of the colony to the United States, which had purchased Louisiana from France earlier that year. Laussat had held his office for only nine months.

At ten-thirty the governor joined a small crowd that had assembled at his stately home near the east gate of the city, on the sprawling plantation owned by Marquis Bernard de Marigny. Among the group that morning were government officials, military officers, and French citizens, who accompanied Laussat on the half-mile walk to the Place d’Armes in the Vieux Carré. After meeting with the American commissioners and handing over the key to the city, Laussat and his companions retired to a balcony overlooking the great, crescent-shaped curve of the Mississippi River at its majestic terminus. There they watched solemnly as below them a French officer lowered the

tricolore

for the last time. As the governor recorded in his journal, “more than one tear was shed at the moment when the flag disappeared from that shore.”

1

The handover that day was the culmination of momentous events on both sides of the Atlantic. In 1801, as first consul, Napoleon had dispatched an enormous military expedition to quell a slave uprising on the island of Saint-Domingue, a French outpost in the Caribbean (now the independent nation of Haiti). Yet after two years of brutal fighting and the loss of 24,000 troops, including his own brother-in-law, who like so many other Frenchmen had succumbed to yellow fever, Napoleon tired of the effort altogether and uttered famously in January 1803, “Damn sugar, damn coffee, damn colonies.”

2

Thomas Jefferson, then in his first term as U.S. president, was only too pleased to assist Napoleon in liquidating his overseas possessions. As it happened, in 1801 American emissaries had tried unsuccessfully to negotiate the French sale of New Orleans, long coveted for its strategic position near the mouth of the Mississippi River and its easy access to the Gulf of Mexico. Jefferson’s officials were thus delighted when in April 1803 Napoleon offered far more, a huge domain stretching deep into the continent’s interior, containing all or parts of fifteen future U.S. states. And the asking price of $15 million was a veritable bargain, working out to about three cents per acre.

If the Louisiana Purchase was the greatest achievement of Jefferson’s presidency, it was also its most controversial, given the dubious constitutional authority permitting such a transaction. Jefferson forged ahead, however, spurred by his aspiration to make the United States an “empire of liberty,” a dream that hinged upon the acquisition of sufficient space to guarantee that it remained an agrarian nation populated by yeoman farmers, whom Jefferson considered “the chosen people of God.” With the Louisiana Purchase, the president believed he had acquired enough land for hundreds of generations of American settlers and, at the same time, dealt a crucial blow to European imperial ambitions in North America.

3

As reflected by the sobs—many of them not even muffled—that Lassaut heard on that bright December morning in New Orleans, not everyone shared Jefferson’s enthusiasm for the American acquisition. And yet while the French were despondent, members of a much larger group—the native peoples of the territory—remained uninformed, though presumably most of them would have looked upon the transfer with scorn or amusement rather than concern. After all, it was one thing to claim land but quite another to possess it, as countless Europeans had discovered during their imperial misadventures in North America. The Indians would have their own say about these matters.

In time the new owners of the Louisiana Territory came to understand that few groups were more stubbornly resistant to American expansion than the Blackfeet, who lived at the opposite extreme of the Mississippi-Missouri river system, some 3,700 miles upstream from New Orleans. By the early nineteenth century, they—and not the French or the Americans—were in full control of the northwestern Plains, jealously guarding against the incursions of all outsiders, native, white, or otherwise.

Nevertheless, even as the

tricolore

came down in the Place d’Armes in the waning days of 1803, plans were already underway in Washington, D.C., to explore and eventually absorb this infinite wilderness, which, in Jefferson’s eyes, held the promise of perpetual renewal for the nascent United States. In short order, Americans would make their way across the continent and enter the orbit of the Blackfeet, first as a mere trickle and later as a flood. This encounter between two disparate peoples, by turns violent and cooperative, would shape the history of the West and the larger nation that claimed it.

A

T THE TIME

of the Louisiana Purchase, St. Louis was a modest but ambitious village of about one thousand residents. Established in 1764 by a New Orleans trader named Pierre Laclède Liguest, the site on the west bank of the Mississippi had much to recommend it, including its position on a high bluff and especially its nearness to the confluence of the Missouri River, just ten miles upstream. Though attracting a diverse group of travelers and traders from its earliest days, the settlement retained its French character well into the nineteenth century, in language, religion, and especially architecture, marked by the white lime application disguising the “meanness” of its many buildings fashioned from mud or stone.

4

For all of its Old World attributes, however, St. Louis took on singular importance for the young American republic when it served as the “gateway to the West” for Jefferson’s Corps of Discovery, which shoved off from its environs on 14 May 1804, bound for the Pacific Ocean.