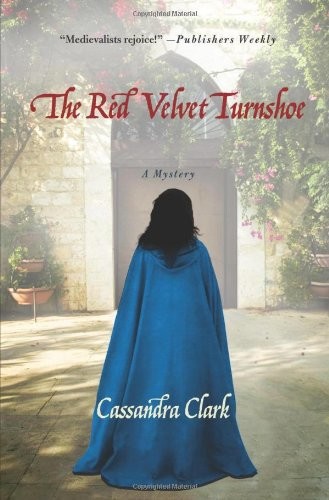

The Red Velvet Turnshoe

Read The Red Velvet Turnshoe Online

Authors: Cassandra Clark

To Kingsford

Black February in the year 1383: the rains started before Martinmas and swept throughout Europe, bringing floods, murrain and the plague. They did not cease until St Lucy’s Day when a brief respite lasted until the new year. After Epiphany they returned with greater force and had not stopped since.

Floods bring famine. Famine brings disease. The Black Death bestowed its grace from town to town. When the buboes appeared the end came swiftly. Bodies were piled in open pits. The lime was spread. Panic flew from Avignon to Stockholm. Paris shut its gates. Cologne and Florence followed suit. In the crowded streets within the city walls, the chanting of the doomed continued night and day while barefoot flagellants scourged themselves and walked through blood.

T

he sound of rain falling in the garth and the gurgling of the sluices became a constant accompaniment to the holy offices of the day at the English abbey of Meaux. Water brimmed over the margins of the dykes, the canal burst its banks, and the land reclaimed by the monks over six generations returned to marsh. Drowned sheep with bloated bodies wallowed in the brackish waters. The abbey itself, pinnacled and serene, was reflected in the standing pools, like a palace in a magic lake.

he sound of rain falling in the garth and the gurgling of the sluices became a constant accompaniment to the holy offices of the day at the English abbey of Meaux. Water brimmed over the margins of the dykes, the canal burst its banks, and the land reclaimed by the monks over six generations returned to marsh. Drowned sheep with bloated bodies wallowed in the brackish waters. The abbey itself, pinnacled and serene, was reflected in the standing pools, like a palace in a magic lake.

In another part of the county, two men were talking secretly within the upper chamber of a castle by the sea. The younger of the two listed allies and enemies and gazed through the lancet at the grey surge of the northern ocean where it reached to the rain-bellied sky. Breakers crashing on the rocks two hundred feet below sounded like a siege-ram battering the castle’s foundations. The guest, shrouded in an expensive velvet cloak, with fur at his neck and a ring on his first finger, inched his goblet towards his host, indicating that he wanted it refilling.

The younger man reached for the wine flagon with an ill grace. ‘So can we count on your brother or not?’ he demanded. ‘After all, he is admiral of the northern fleet.’

‘Leave my brother to me,’ advised his guest evenly. ‘More important is this question of sedition.’

‘My bloodhound has been dispatched. He’ll finish the job.’

The man in the velvet cloak raised his brows.

‘I was sent north with a task to do and I’m doing it,’ snarled the younger man.

The guest sipped his wine and made no comment.

At this same time shortly after Candlemas when darkness came early, a lone figure appeared out of the gauzy air not far from the abbey of Meaux. He was wading through the puddles on a ribbon of track that wound through the marsh, travelling from an easterly direction, from the iron-bound coast across the moors. It meant the wind was at his back so that his tattered cloak flew before him and hurled his hood over his face.

As he approached the abbey his progress slowed. Before risking each step he began to prod the pools before him with a stave of hazelwood and only when he was convinced that he was not going to plunge in up to his neck did he go forward. In this way he reached the drier ground of the foregate and came to a halt. There was no one about. Pulling his hood more securely over his face, he turned onto a narrow path that ran along beside the abbey wall. Still testing the ground like a man who trusts nothing, he proceeded until he came to a back gate set under a small, stone arch. He slipped through like a shadow. The gate creaked as he closed it, the sound instantly lost in the roar of water gushing between the banks of the canal.

Hastening into the shadow between two buildings, the traveller peered across the garth towards the gatehouse. A few flurries of snow were beginning to fall from out of the freezing fog that crawled over the slant rooves.

He had been walking across country for five days. His boots were encrusted with mud to the knees. His nails were black-rimmed. The hand-bindings worn as protection from the pinching frost were torn and caked with dirt.

A guttering flare was brought out of the gatehouse, lighting up the scene and gilding each separate snowflake, as if gold coin fell from heaven. The traveller watched them turning and tumbling out of the void.

A group of pilgrims had preceded him. They were jostling in a cheerful bunch within the lambent glow of the flare while a ruddy-faced porter took down their names and destinations. By the sound of their voices they relished the imminent prospect of food and bed.

A bell began a summons to the next office. Compline, he thought with satisfaction. He had timed it perfectly.

Joining the tail-end of the group, he soon found himself sitting in the warmth of the refectory, holding out a trencher for some thin gruel. No one questioned him. He bit into the bread. It was sour. As soon as he had taken his fill he would get a horse from some unsuspecting fellow traveller and be on his way. He glanced round at the other guests. They were living in a dream of angels and incense; the real world was a different place.

Living rough, dodging the law all winter, he had hatched a plan in the long hours of darkness. An old Welsh astrologer in Scarborough market place had set his seal on it. ‘The time is nigh!’ he had told him and a lot more besides that didn’t make sense. But holding back until the time was at its most auspicious made it sweet.

It had been November when the nun had nearly done for him. He could be dead now but for his brute will to survive.

His fingers touched the scar that ran crookedly down the side of his face. She had disfigured him as surely as if she had hurled the rocks at him herself. God’s bollocks, the mare had all but drowned him.

Wiping his mouth, he got up and left the pilgrims cackling among themselves.

He had business here. It meant gold in his pocket. But after that he would be off, first to the nun in the priory at Swyne, then on the road to the killing fields. He would go by way of Ravenser, taking ship to Flanders, then over the mountains and down into Lombardy. There he would join one of the free companies, maybe the one commanded by John Hawkwood, the greatest mercenary of them all.

His grandmother, the heartless old crone, had told him one thing: shift or starve. But he had had enough of starving. And he had had enough of being treated like a dog in his own country. He would get clear of the place and make his fortune. It was sure, neither God nor man would do it for him.

But first, and maybe best, to Swyne.

A

N ARROW FLEW through the air with a hiss. There was a thump as it hit the target. Hildegard, clad in her white habit of unbleached stamyn and high knee-boots, went to withdraw it.

N ARROW FLEW through the air with a hiss. There was a thump as it hit the target. Hildegard, clad in her white habit of unbleached stamyn and high knee-boots, went to withdraw it.

The orchard where she was practising was covered in mist. It was a bitter February morning and the bare branches of the apple trees were rimed with frost. But at least it had stopped raining and the snow had not settled.

From over by the wattle fence separating the orchards from the priory kitchen garden, a voice called a greeting. It was Lord Roger de Hutton’s steward, Sir Ulf. Lanky and good-natured, he wore a smile behind his clipped blond beard as he asked, ‘Expecting trouble, Sister?’

Hildegard watched him wade through the wet grass towards her. Her spirits lifted. ‘What brings you over here, sir? Life at Castle Hutton too dull for you?’

‘Never! Not with Lord Roger around!’ His glance fell to the bow she was holding. ‘Are you sisters planning on becoming archers as well?’

‘In time, maybe. It’s just a precaution.’

Ulf towered over Hildegard although she was a tall woman and when he looked down into her face, flushed now with the cold and the exercise, his eyes took on a serious cast. ‘You’ve no need to worry. The grange you’ll lease from Roger has never been attacked. Not even when the Scots were raiding every summer. It’s too remote.’

‘I know that. But there’s no point in trusting to luck. Not in these times.’

She didn’t need to explain. The people’s rising in London during the feast of Corpus Christi when young King Richard was still only fourteen had been the culmination of years of unrest. The leaders and their most prominent followers had been exterminated under the orders of John of Gaunt, the king’s uncle, and those who had survived the bloodbath had fled to the woods. Now, two years later, they still had no choice but to live outside the law in poverty and desperation. The threat that worried Hildegard, however, was not from the brotherhoods and companies of the outlawed. It was the threat of invasion by the French with the Duke of Burgundy at their head.

‘Whatever happens we’ll be prepared,’ she repeated.

‘You should stay here at Swyne where you’d have the protection of my men-at-arms and the stout men of Beverley,’ Ulf advised.

‘But if there is an invasion, Roger’s going to call on you to muster to the king’s aid. You won’t be here to defend us. And if intelligence brought from France is correct, it’s likely to be at Ravenser where they’ll try to breach our defences, not in the south where they know they’ll meet with opposition.’

Ulf frowned. She was right. Once married to a knight killed some years ago in the wars in France, she had no illusions about the dangers they might face if the rumours turned out to be true.

If it came to open battle, the northern landowners like his own lord, Roger de Hutton, feared that the abbots of Rievaulx, Jervaulx, Fountains and Meaux would place their allegiance with their mother house in France. As Cistercians they were allied with Clement, the false pope in Avignon. England supported Pope Urban in Rome. With rival popes throwing in their support it could become a bloody contest for power with nothing less than the Crown of England at stake.

He took her bow and ran his hands over it. ‘What’s this?’ he asked, trying to keep his tone light. ‘Spanish yew?’

‘Nothing but the best for us.’ Hildegard smiled, knowing what was on his mind.

‘Your prioress must have money to burn.’ Without appearing to check the distance or the target he loosed off an arrow. It hit the bull squarely with a thump.

Hildegard took back her bow.

‘I doubt whether I can match that,’ she said. Taking careful aim, she loosed an arrow. To her satisfaction it split Ulf’s arrow firmly down the middle.

After vespers later that same day a servant found Hildegard in the cloisters and informed her that the prioress wished to speak to her. She made her way across the garth to the prioress’s lodging.

It was bleak inside. The stone antechamber had nothing in it but a chest bound in iron standing on the cold flags. The prioress herself was nowhere to be seen but candlelight glowed from within her private chapel deep inside the building. Hildegard stepped over the threshold. As if formed from the frosty air itself, the prioress appeared in the distant doorway. She gestured for the nun to approach, then closed the door behind her.

It felt even colder inside the chapel. The massive slabs of York stone from which it was constructed trapped the air and made it dank. Several guttering candles stood on a small altar. Between them a panel painting depicted the virgin and child. It was the only ornament. Blue and gold, it glowed in the flames’ light, bringing the incandescence of magic to the vault.

The prioress’s face was framed in a tight wimple of spotless linen. She had a raw, unprotected look, her narrow nose somewhat red at the tip, that made her seem more frail, more human. As usual, however, she conducted the conversation while standing.

‘I have an errand for you, Sister. One I believe you may relish. But first, tell me if anything interesting passed between you and Lord Roger’s steward this morning.’

‘I understand he was here to discuss that matter of litigation over the grange at Frismersk,’ replied Hildegard.

‘Oh that, yes, that’s Roger’s excuse for sending him. Did he mention where his lord was?’

‘He told me he was on his way to Meaux. Ulf was sent on ahead and that’s why he decided to take the opportunity to come over here to settle things with us.’

‘Good. And it is settled – and not at all to our disadvantage.’ The prioress smiled with pleasure. ‘So Lord Roger’s descending on

Meaux, eh? Now why would he want to do that? Is it only to see the dispatch of the staple he’s sending to Flanders?’

Meaux, eh? Now why would he want to do that? Is it only to see the dispatch of the staple he’s sending to Flanders?’

‘Ulf said something else, about using it as a base for meeting an armourer from York.’

‘He did, did he?’ This piece of information evidently interested the prioress very much but Hildegard could tell her nothing more.

The prioress, however, hadn’t finished. ‘He brought Roger’s clerk with him, I understand?’ For someone who rarely seemed to leave her cell she was remarkably well informed.

‘He did.’

Hildegard had met the clerk, briefly, and thought him a gaudy fellow, dressed in a most unclerical green hood with a long liripipe of purple and red, which he wore twisted round his head in the manner of a sultan.

‘Something’s afoot,’ murmured the prioress as if forgetting for a moment that one of her nuns was present.

Hildegard paid careful heed. Perhaps she was being asked to find out why Roger suddenly needed the services of an armourer. Maybe she would even be ordered to Meaux to see what was going on. The thought of the abbot, Hubert de Courcy, distracted her for a moment until she brought her attention back to what the prioress was saying.

When she realised what she was being asked to do, Hildegard gazed at her in astonishment.

Back in the cloister she paced the stones, scarcely aware of the deafening roar of rainwater jetting from the overflowing gutters.

It began with Alexander Neville, the Archbishop of York. He had asked the prioress a most extraordinary favour. He wanted her to send a nun secretly to Rome to bring back the legendary cross of Constantine.

When Hildegard had looked sceptical the prioress had taken time to explain. Everyone knew that Constantine had been converted in York where he had been a mere consul – although some still claimed it was a deathbed conversion. Be that as it may, his father, the Roman emperor, had named him as his successor. There were six other claimants. But when Constantine faced the army of Maxentius at

the Milvian Bridge near Rome a cross of flame had appeared in the sky. It was seen as a sign from God that he was the chosen emperor. The story went that living fire inscribed the words: ‘In this I will conquer.’

the Milvian Bridge near Rome a cross of flame had appeared in the sky. It was seen as a sign from God that he was the chosen emperor. The story went that living fire inscribed the words: ‘In this I will conquer.’

The archbishop had decided he wanted the small wooden cross Constantine had carried into battle. ‘Bring it home to York – and at any price,’ his grace told the prioress, hinting that the reason he wanted it so badly was so he could compete with the Talking Crucifix of Meaux. Famous in its own small way for its prophetic powers, it attracted pilgrims to the abbey in their hundreds, bringing money there instead of taking it to the shrine of St William at York.

The prioress had given Hildegard a thin smile. ‘That’s his avowed reason for wanting it back,’ she had said, ‘but we can assume there’s more to it. I don’t need to tell you how well his grace will reward us should we accomplish this small errand.’

Small errand? The long and dangerous journey to Rome was no small errand. And Hildegard’s alarm had increased when she heard that the cross, its whereabouts kept secret for centuries, was believed to confer almost supernatural powers on those who possessed it. With Gaunt’s opposition to King Richard mounting by the day, it was clear the cross would be a valuable asset for Gaunt, or even a talisman to be used by the king himself against his enemy.

They had been alone and unobserved in the private chapel. The walls were thick and the candles on the altar shed only a weak light. Whatever was said here would disappear like smoke into the shadows and yet Hildegard had nerved herself to query the archbishop’s allegiance.

The prioress held her glance, her eyes unexpectedly luminous, and withheld a direct answer. ‘Tread carefully, Hildegard,’ she warned. ‘Remain unnoticed. There will be spies from Avignon, Burgundy, Flanders and from England too. No one, not your confessor, your closest confidante, nor any priest or monk – and certainly not the lord abbot of Meaux – must know that you are on the trail of something with such importance for the safety of our king.’

Hildegard shuddered. A feeling of dread had swept over her but she had risked an objection. ‘I was promised that when I found a

suitable grange I could set up my own religious house with seven nuns to help heal the sick and teach the children of the villeins to read and write. Yet now—’

suitable grange I could set up my own religious house with seven nuns to help heal the sick and teach the children of the villeins to read and write. Yet now—’

The prioress had nodded. ‘That promise will be kept.’

‘But—’

‘When you return from Rome you will find no further obstacle to your desire. Indeed,’ she added significantly, ‘you will find help from the highest quarters.’

The usual forthright manner of the prioress had softened as she shifted one of the candles as if its guttering flame were a distraction.

When she had repositioned it she said, ‘I suggest you take one of these new bills of exchange instead of gold. Easier to carry. But don’t mention it unless absolutely necessary. I also suggest a pilgrimage as a suitable cover for you. And of course it will be prudent to approach the lord abbot for permission. Be warned,’ she fixed her with a stern glance, ‘we do not know where his loyalties lie. He must know nothing of your true purpose!’

Hildegard had one further objection, even though she knew it was useless. ‘The abbot will be surprised to find I wish to go on pilgrimage at such a time—’

‘On the contrary,’ the prioress had countered, ‘he will think it perfectly natural to seek confirmation of your faith before embarking on the toil of setting up a house of your own.’

There was no refuting her. Hubert de Courcy might be astonished by the abruptness of her decision but he would not be surprised by her alleged purpose.

Other books

The Man Within by Leigh, Lora

Hell Rig by J. E. Gurley

Close Quarters by Michael Gilbert

Move to Strike by Sydney Bauer

God's Fool by Mark Slouka

Simon Says (Friends and Lovers) by Colbert, Gillian

The Best Australian Essays 2014 by Robert Manne

The Guardian Herd: Stormbound by Jennifer Lynn Alvarez

Cannot Unite by Jackie Ivie

Broken Wings by V. C. Andrews