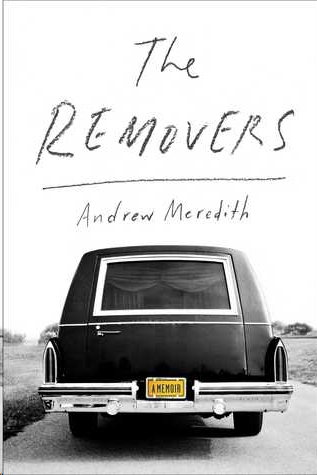

The Removers: A Memoir

Read The Removers: A Memoir Online

Authors: Andrew Meredith

Thank you for downloading this Scribner eBook.

Sign up for our newsletter and receive special offers, access to bonus content, and info on the latest new releases and other great eBooks from Scribner and Simon & Schuster.

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

To John Klein

Love is not love

which alters when it alteration finds,

or bends with the remover to remove.

—W. S.

We all inherit death, Andrew, but not death alone.

I give dogwoods in the sun to you, who cling like life to bone.

—W. M.

1

Dad parks the hearse at the curb under a pink-petaled dogwood, in the glory of that first balmy April Saturday afternoon. We’re on Castor Avenue in front of a tan brick apartment building, treeless courtyard, three stories high, a block long but invisible, a place that marks the edge of our Philadelphia neighborhood and the next, a structure populated by pensioner bachelor mailmen and mothers and toddlers learning English together. At the rec center baseball diamond across the street, screams of “Go!” follow an aluminum plink. At the corner, tulips in yellow, red, violet, planted to partition the sidewalk from a tiny row house lawn, salute a crew-cut man in a tank top, gold crucifix swinging as he soapy-sponges his four-wheeled stereo. The fried onions from the grill at the steak shop a block away whisper that the cold and dark have passed and we’ve been delivered somewhere

better, and yet inside our little brick houses these last six months a secret part of us wondered: is this the year winter doesn’t end? A girthy old woman in her sleeveless summer housedress, sunlight warming her arms for the first time this year, hoses the dirt under her rosebush. She looks like a Helen. She might be a Carol. An ambulance lines up at the red light like all the other cars, in repose, maybe coming back from an oil change.

Dad and I leave the car and walk into the courtyard where a man in a fishing hat and a yellowed V-neck T-shirt, maybe sixty-five, sucking a cigarette, raises a hand. “I’m the brother-in-law,” he says. It’s sunny, humid. Dad is fifty years old, solidly built, clean-shaven, glasses, gray hair shiny and wavy like a trial lawyer’s. He cuts his own hair in the bathroom mirror because he knows he can do better than any barber left in our neighborhood. I am a head taller than he, gangly, a day past clean-shaven, with glasses, and, though not balding or a mental patient, I keep my hair in a self-inflicted buzz mostly because I assume I would screw up a scissor cut. If the brother-in-law had met us in different circumstances, when he wasn’t in shock, he might’ve noticed the same long nose on both of these removers. Or at least he would’ve noticed the sweat beading on our foreheads. Or my polyester suit: a fledgling. Or how sharp Dad looks—suit of lightweight wool, loafers polished and tassled, white pocket square, as if he’d slid dressed like this out of the womb. But the brother-in-law doesn’t really see us. He says hello, of course, and thanks us for coming, but the living parts of him have retreated far away behind the corneas. I recognize this kind of distance.

Besides, the brother-in-law has never seen us before and will never want to again, these who’ve shown up on what I guess is the worst day he’s had in a while. Maybe ever. We are nobodies. Strangers. We aren’t the funeral director who perches every Sunday in the front pew at mass. We are men made to be forgotten, here to take away the shell of his brother-in-law. He’ll never think on us again. I feel right away a rush from this. We’re paid to be invisible. And yet there’s another part of me—reasonable, accountable, button-down—that likes how useful this work makes me. The brother-in-law says, “Carl lived alone. We hadn’t heard from him for a few weeks, which wasn’t strange, but the neighbors called the cops today about a smell.” He opens his eyes a little wider and shakes his head. “He’s been in there awhile.”

Just as I had dismissed my dad’s assurances on my first removal, I brush aside the brother-in-law’s warning. He’s not used to these things the way we are, I think. I assume I’ve seen and touched and smelled the limits of the job’s gruesomeness. By the time we’ve walked the few paces to Carl’s front door, I know I’m wrong again. His windows and the door are shut, but what awaits us seeps out. At the first whiff my heart feels like it might come bursting through my armpit. Dad looks at me and says, “We’ll be okay.” When he opens Carl’s front door I have never smelled anything worse—imagine being waterboarded on the hottest day of summer with the maggoty brine dripping from the back of a garbage truck—and we’re still fifteen feet from the closed bedroom. We move to the back of the apartment, wheeling the stretcher, breathing through our

jacket sleeves. We stop just outside his room. Dad and I don’t speak, but share a look. I know, in my eyes at least, there’s terror. How bad will it be in there? What will this guy look like? But there’s also an element of disbelief: Have our lives really brought us here? Is Dad the guy with a book of poems? Am I the kid who won a full ride to college a few years ago? A split second where the job’s simple awfulness brings into focus the downward trajectory of our circumstance.

When I was old enough to know the kind of place we lived in—blocks and blocks of brick row houses dotted occasionally with a brick factory or a stone church, and cut through by train tracks and highways—one of my favorite things Dad would do was drive the two of us along Snake Road, a stretch he called “the country in the city.” Only a mile from our house, Snake Road runs through woods, the only such break in our part of town. Every few months in these first years of my awareness of the world, he would wind us through the trees. Every time, as we came back into the grid of the neighborhood, it felt to me for a finger snap of a moment that we belonged to that wilderness more than we did to our house, and belonged to each other more than we did to my mother and sister inside it.

It’s time to open the bedroom door. Never before have I felt anything as dreadful as what hits us when we enter. The windows are closed—his last night, probably at least a week

before, must have been a cold one—so the stench surges at us like a crashing wave, coating our faces and rushing into our nostrils and mouths. My stomach closes like a fist, shoulders jump toward ears. My scalp tingles. The odor is an exponentially more putrid relative of late afternoon low tide, when the summer sun has spent a full day cooking the rotten gunk on the bay floor. But that is an inadequate comparison. In the context of a stale, dilapidated apartment building, Carl’s stink screams an urgent and violent disharmony. We smell death.

Lying on his back, Carl looks like any napping retiree, except he’s purple. And gravity has pulled almost all the liquid in his body into his lower hemisphere—his back and ass and the backs of his legs—which makes him a head to toe bedsore, a seeping blister ready to gush. As awful as it is to look at Carl and smell him, being that close to him somehow shoos away any fear or hesitation. Pity fills the void. He’s just a poor soul who happens to be rotting in his bed. And it’s difficult, I’m finding, to handle an older man’s corpse with your father—a man, odds say, you will one day bury—and avoid thinking of your father’s death. And when the older man you’re removing lives alone in your neighborhood, and your father and your mother don’t get along, and you expect they could be living separately any day now, it’s hard not to imagine your father dying like this, in an anonymous building in Frankford, going rotten like a pack of chicken breasts forgotten in the trunk, and you playing the brother-in-law’s role, you letting yourself in and wading through the death smell to see him melting into his mattress. It’s strange, maybe inappropriate, to include my

fifty-year-old father in a thought like this, but I wonder if the two of us will make something of ourselves before that day arrives.

We know we can’t or, rather, don’t want to breathe near Carl, so we decide to work in breath-long shifts—one guy in the bedroom at a time—like kids in the deep end of a pool trying to grab a quarter off the bottom. But this strategy can only last so long. Lifting the body in its bedsheet, the norm for in-bed removals, is out of the question for Carl. If we hoist him like that, the pressure of his weight against the sheet will split him like an overripe peach, with fluids rushing through the fabric, leaving a mess we don’t want to witness or clean up. Instead we’ll have to fasten him to the plastic sheet we’ve brought along, a tool called the Reeves.

Lined with narrow boards, the Reeves is firmer than a bedsheet, and so offers a better distribution of support of the body when lifted, and since it’s plastic, no leaks. The drawback, though: using the Reeves requires not a small amount of handling the deceased. The man who taught me to throw a baseball now stands on the right side of the bed and reaches across for Carl’s left arm and left leg. “Like this,” he says through a grimace. When he pulls the limbs up off the mattress, I shimmy the Reeves under as far as I can. Then we switch. In Carl’s case, lifting him means loosing all the stink caught between him and the bed. It also means gripping his flesh, which, through rubber gloves, feels like squeezing a Ziploc bag filled with tomato sauce. We work like a pair of gymnast surgeons, summoning a precise mix of speed and delicacy that I have never imagined

within our genetic grasps. In a few minutes the three of us are outside in the fresh air of the courtyard. The brother-in-law has disappeared.

The ride to the funeral home is its own horror, especially at red lights, when the air stops moving. But breathing in the open-windowed car with the AC roaring doesn’t compare to breathing in Carl’s coffin of a bedroom. Unloading him from the Reeves onto the embalming table in the air-conditioned funeral home morgue is also a diminished echo of its mirror act. And then we go home and life is normal. I eat a forearm-size Italian hoagie leaky with oil and tomato drippings, without thinking of Carl’s seepage. I talk to my mother in the kitchen and watch her go silent and stiff in the shoulders when my father comes in. I go to Gazz’s apartment that night and we pound Miller Lite while his girlfriend and his baby sleep in the other room and we watch the Sixers on mute and he drags out his boom box and puts on “Couldn’t You Wait?” by Silkworm and then I play Todd Rundgren’s “We Gotta Get You a Woman” and he chooses “Dry Your Eyes” by Brenda and the Tabulations and then we play “Bobby Jean” and Bruce—Bruce, our beloved uncle (long lost, made good); Bruce, on our parents’ stereos since the crib; Bruce, patron saint of Philly white boys’ first sips of disappointment; Bruce, no last name required or ever, ever used—tells us

we liked the same music we liked the same bands we liked the same clothes

, and so begins another night of

telling each other we were the wildest

and pulling one gem after another from Gazz’s laundry basket loaded with CDs and cassettes.

Hours later I drive home drunk up Tulip Street hollering along to Pavement’s “Fillmore Jive.” “

I need to sleep it off

,” I sing. When it ends I rewind and do it again. I’m only a few weeks into this funeral business and already I’m feeling that a certain gift of mine—becoming okay with anything that happens even as I am powerless to change it—is being put to the best use possible. There are all sorts of careers that need active, aggressive personalities, but not this one. The remover affects a normal life and then the little plastic matchbox in his pocket vibrates and he goes and puts on his black suit and in half an hour he’s pulling your dead ass out of bed with his knees, not his back. The dead body picker-upper, he accepts what life brings. He’s not out evangelizing for salad greens and thirty minutes of cardio. He’s not caught up fighting the unfightable. He doesn’t turn his anxiety into fake-hustle like a New Yorker. He accepts. He’s a model phlegmatic, like William Penn. He is a Philadelphian by nature. You’re dead and you need a lift.

A month before my father and I picked up Carl, I was unemployed. I was twenty-two. I lived with my parents, who hadn’t spoken to each other for eight years, in Northeast Philadelphia, in a neighborhood called Frankford, in the row house I grew up in. On this night I was doing my usual thing of standing on the front steps after everyone had gone to bed, getting buzzed on a string of Camel unfiltereds. I waited for my parents to go upstairs because I didn’t want my mother

to know I smoked. My younger sister, Theresa, my only sibling, was living across town in a dorm at the University of Pennsylvania. Alone out there on the top step I became the star of my own movie, in my shearling coat, smoking my Camels, flicking away the butts, greeting passing cars with squinty tough-guy looks, though it was too dark for them to see my face. I liked to smoke six or seven in a row to feel light-headed, to feel different than I did in the house, to stain my fingers yellow. On this night I brought my Walkman out so I could listen, again, to Pavement’s

Crooked Rain, Crooked Rain

. I was looking for something in that album, some clue to myself that could be illuminated by the feeling its songs gave me—a sense of spiritual soaring. How could they grant me such lightness, I wondered, when every other minute of the day felt like lead?

Every fifteen minutes or so a bus pulled up at the corner. How odd for a lit room of strangers to appear out of the dark, stop, roll away. The J, the K, and the 75 all stop at Oakland and Orthodox. Each route starts in Frankford, the place where I had always lived, where my parents had lived almost their whole lives, where my parents’ parents had lived, where my mother’s grandparents and great-grandparents lived back to when these blocks were farms. And these three routes all connect Frankford to the northwest part of the city: Logan, Germantown, Olney. Olney’s where I had ridden these buses to most often. As a toddler sometimes I would ride the bus with my father to La Salle College, where he taught English and from which he’d graduated in the early seventies. And

up until two years previously, I rode the bus there to go to class at La Salle myself. But I dropped out in the middle of my junior year. Not a huge failure, then again it wasn’t the flunking out that worried me. I used to be smart. Used to be funny. Now I was the kid who waited for everyone to go to sleep so I could smoke. I’m not a smoker. Now I was the Silent Kid, and Pavement’s singer, Stephen Malkmus, was the one person who knew how to talk to me. “

Silent kid . . . let’s talk about leaving

,” he says. “

Come on, now. Talk about your family

.” I don’t want to talk about my family, Malkmus. I practiced unsophisticated astronomy through the light pollution of streetlamps. Orion! I rarely ventured off the top step. I could have gone for a walk around the block or even up and down the street, but I didn’t want to risk it. There could be possums. Periodically I scraped my sneakers on the concrete to spook anything nocturnal that might’ve been creeping in the hedges. Also, I didn’t want to get jumped. I didn’t risk much in the daytime either. The sweep of my ambition was confined to dubbing mix tapes for Gazz and hunting in Salvation Armies and Goodwills for secondhand T-shirts I could see Malkmus wearing. The voice in my head that told me this was all wrong, that days and nights like this were sins against myself, I did my best to drown out with Pavement and sports talk radio. I was dreadful broke.