The Ride of My Life (13 page)

This was the first 900 I pulled in March, 1989 in Ontario, Canada. It was my second pro vert contest, and only the second time I attempted this trick. (Images courtesy of Eddie Roman)

TURNING TRICKS

The subject of history has always left me a little disengaged. I never wanted to read about it, I wanted to make it. I turned seventeen years old in January of 1989 and decided to usher the new year in by turning pro. It was at the biggest King of Vert contest to date, held in an arena in Irvine, California. There were commercials on the radio leading up to the comp, and ads on MTV. It was sponsored by Vision Street Wear, a powerhouse force in freestyle at the time. The Vision skateboard company was the first action sports brand in the eighties to really break into the mainstream, and they wanted to own a piece of bike riding. Blaring

STREET WEAR

logos were wrapped around the trunks and backs of half the riders in the sport like a giant rash.

The event resembled a rock concert, complete with Intellibeam lighting system, fog machines, jumbo TV screens, a monster ramp, and about five thousand superfans foaming at the mouth in the stands. I started the evening by entering in the amateur class.

I won. The hardest part was saving some of myself for what was still to come. Immediately after the amateur competition they ran the pros. The rules didn’t prohibit it, so I resigned my amateur status and signed up for both the pro class and the highest-air contest.

Feeling anxious, energized, and high on my decision to leave the am ranks behind, I rolled in for my first run as a pro. Nothing had changed, but then again, everything was different. This was the big boys class, and from now on at contests I would be riding with [and technically, against) heroes I had grown up watching: Brian Blyther, Ron Wilkerson, Josh White, Mike Dominguez, Craig Campbell. These guys weren’t just peers, they were people I’d had postered to my bedroom walls as a kid. I remembered having my mind blown seeing old photos of Blyther and Dominguez riding cement skateparks. Now it was time to test myself against the standards my idols had set with their style, smoothness, and sick riding.

My first run as a pro, I unleashed everything I had: supermans to barhops, big 540s, a barhop fakie; and I busted out with a new trick I’d just invented. I blasted about five feet out of the halfpipe, removed all my limbs from bike contact, then grabbed back ahold in time to reenter the ramp backward; I called it a nothing fakie. It updated the famous nothing air that Wilkerson had practically patented when he’d invented them a year earlier. For the finale, I tried (and missed) a double tailwhip. At the end of the contest there was brief break while the judges tallied their scores. The crowd had seemed to be on my side, and I waited for them announce the results, wondering who would come out on top.

They results of the pro finals were announced in reverse order, starting with eighth place. By the time they got to third place (snagged by Joe Johnson), I still hadn’t heard my name called. Then they called Brian Blyther’s name as the second place winner—his run had been in his typical high-altitude soul storm style, looking effortless as he carved up the ramp like a Thanksgiving bird. Brian had capped off his last run trying a 900, but he didn’t have enough spin and came down sideways, which sent him limping off the plywood with a fresh crack in his tibia. Suddenly, my brain did the math; I hadn’t heard my name in the pro finals results yet, and if Blyther got

second

that meant…

That night at the Irvine KOV I made history. I won the amateur contest, won the pro contest, won the highest-air contest (a little over ten and half feet), and won the 1988 Amateur of the Year series title. My first hour as a professional, I’d made $2,200 and won two snowboards. Happy birthday to me.

The first KOV contest of the 1989 season went down in Waterloo, Ontario, in Canada. I had a broken thumb from trying variais on my bike (never have learned ’em) but was feeling good enough to enter the comp. I had my hand cast molded in the shape of my grip so I could ride. It felt solid during my early runs, and the crowd was pretty loud. I got a wild hair and decided to try a 900 in my final run.

To pull a 9 would be a pretty big deal, as it had never been done in snowboarding, skateboarding, or bike riding. It was a mythical “Wish List” trick among the top contenders in all three sports. The trick had been a biker crusade for years; Mike Dominguez had been trying them since 1987 but never landed one in public, and he wouldn’t deny or confirm that he’d actually pulled it off in his backyard ramp. Brian Blyther had also twirled a few but had missed the mark, and British upstart Lee Reynolds came close and lost teeth in the process.

I saved the 9 for the last trick of my final run in Ontario. I felt it in me. The first one I ever tried, I didn’t get all the way around on my last rotation, and I went down in flames. It felt close, though. I rolled in for another go, pumped a few feeler airs around five feet out while I psyched myself up. Then I fired off the coping spinning furiously. This time I committed all the way, leading with my shoulders and head. The thing about 900s is the horizontal rotations happen in a flash, because you have to spin so fast: 180 degrees, 360, 540, 720… 800… 850… 900. I was airborne for two seconds, then

Boom

! I landed low on the tranny but rode out of it. The stadium of Canadians went ballistic. I was still rolling across the flat bottom when I got tackled by fellow pro Dino Deluca, who led a stampede of about a hundred and fifty very excited people onto the ramp. I was raised onto shoulders in a mosh pit of glory. I’d put my stamp in the history books, the contest was over, and I won. It was a cool moment.

For a while thereafter, the 900 became a cross I had to bear. It was the miracle that everybody wanted to witness firsthand, and I was the only person who had proved it was possible. The expectations were high every time I rode at a contest, and the fans didn’t so much request the 900, they demanded it. One of the next contests I went to was billed as the Freestyle War of the Stars—hyped as the biggest bike event ever, with $20,000 in cash up for grabs. Before I could even start my run, the crowd was chanting for a 900, breaking up my concentration. I figured I might as well get it out of the way, so I dropped in and ripped off a 9 as my opening trick. My next run I did six back-to-back 540s. I also tried a run with a bouquet of helium balloons strapped to my back (Spike Jonze’s bad, bad idea]; I spun a 540 and the balloons tangled around me like a spiderweb, nearly taking me down. I ended up winning the event. Within a few days I realized, like every other pro who entered, that my rubber paycheck had bounced sky high. Yes, welcome to the bike recession.

There was another trick I’d wanted to learn for years, so Steve and I brought a launch ramp down to a nearby lake, like scientists setting up lab equipment. The first guy in the sport to pull a backflip was a cat named Jose Yanez. He used toe clips to keep his feet attached to the pedals, and then did the trick ramp to ramp. For his skill, Jose scored a steady gig with the circus. I was on a mission to bring flips to vert, but it was a risky riddle trying to figure out how to do it without breaking my neck. Hence, I started doing backflips off the dock, into the water. After a few soggy trial runs off the dock, Steve and I returned to the Ninja Ramp and built a platform extending out of the transition. The new section of deck stretched away from the coping and out over the middle of the ramp, so it would catch me as I carved my flips off the vertical wall. I scoured the Dumpsters outside Goodwill and found a few old mattresses and couch cushions, and those became my low-tech landing pads. I practiced pulling flips off the coping, hoping to land on the platform. The first few attempts were ugly, and painful. A couple times I missed the platform, landing upside down from fourteen feet up. I woke up puking.

Slowly, I learned the mechanics of the motion and began to lower the platform to simulate the feel of landing a flip on a solid surface, until finally I just took it down—I had to make the trick or trash my body. My goal was to pull a complete flip, coming into the transition backward and riding it out as a fakie. To make it, I needed at least six feet of air so my head would clear the coping. It was the kind of stunt that required 100 percent conviction each time. I practiced them every day until I had the flip fakie pretty wired, landing high on the transition rather than jarring into the flat bottom. Then, I got invited to France.

Every year there was an annual spectacular race in Bercy stadium in Paris. The French magazine

Bicross

put on these events, and they were the same folks who’d arranged the KOV invitational contests and demos. The French promoters loved to make a spectacle, regardless of the sport. They had been known to fill the Bercy stadium floor with six feet of water and hold indoor jet ski races, or bring in huge fans and create an artificial windsurfing ocean. The Bercy BMX races were always quite the production, and the trips were legendary. The previous year I’d gone out to do demos with Brian Blyther, and we were lowered into the stadium from the ceiling in a boxing ring to the “Theme from Rocky.” Nine thousand screaming French lunatics greeted us, and we put on a good show. On the last trick, though, I did a no-hander over Brian, who was doing a 540, and something went wrong. Brian slammed, breaking his ankle.

My demo partner this time around was the best flatland rider in the world, Kevin Jones. The fact that every ground wizard had copied most of his moves didn’t seem to affect Kevin in either a positive or a negative way—his true focus was just riding his bike, regardless of who took note of him.

Since the Bercy event was a race, Kevin and I were outnumbered by a lot of pro BMX racers on the trip, including Mike King, Todd Corbitt, and Matt Hadan. Spike Jonze was there shooting for Go magazine (with advertising dollars dwindling,

Freestylin

’ and

BMX

Action had morphed into a single title covering both sports, called

Go

). On the Paris trip, Jonze, Jones, and I spent a lot of time hanging out together. The trip contained the usual trappings of a luxury vacation custom-tailored for a biker. We rode the insane brick-banked lunar surfaces and planters in front of Les Gulleiottes in Paris—basically a building façade with perfectly shaped craters and ridable pillars, turning it into a public

skatepark that nobody planned. We all got in a few food fights with the rock-hard bread of France, which our hosts kept telling us was “breakfast.” There were numerous bewildering attempts to use tactical French on random people, introducing ourselves as “helpful monkeys,” “moody jugglers,” “crazy eggs,” and whatever other phrases we could piece together in our translating dictionaries.

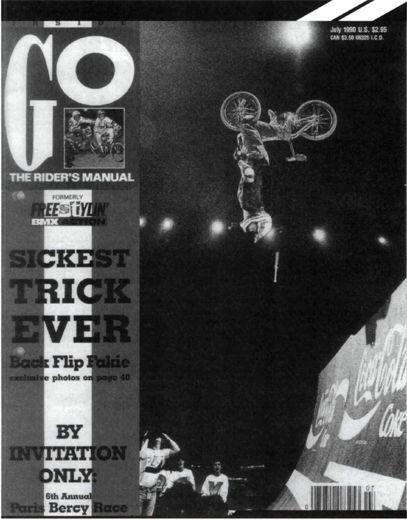

The historic cover of Go, The Rider’s Manual. This was the public debut of the flip fakie, shot by Spike Jonze in Paris.

Kevin Jones and I dressed up before the show at the Bercy Stadium in Paris, France.

After the last stadium race was run, it was demo time. Just before we started, Kevin and I were handed silver space suits and helmets. We thought it was a joke, but, the promoters actually wanted us to put them on. We would be lowered in a smoking space shuttle and emerge from the ship wearing the suits [which made us each look like Q-Bert, the video game character). There were French girls dressed as cheerleaders on the spacecraft. And the theme song, as I recall, was “2001: A Space Odyssey.” When we touched down in the stadium I was supposed to get on the mic and greet our fans with a “Je m’appelle Mat Hoffman.” All I wanted was to ditch the fruity silver suit and get on my bike.

The show went well; Kevin ripped up the ground with his trademark swirling flatland boogie, and I pulled all tricks out of my bag, saving the best for last. While I caught my breath I called Spike over. “Put in a fresh roll and shoot a sequence of this next one,” I said to him, trying to sound casual. “I’m going to try a flip.” Spike found his angle just as I was ready, and I hit the Coca-Cola quarterpipe at full speed. I pulled off the coping, leaning back as hard as I could, and got about six or seven feet out as I peaked. I remember being upside down, seeing flashbulbs popping. I don’t think the French spectators were ready for what they saw, but the reaction was thunderous. I landed hard and slid out, but I guess that didn’t matter. History was made. People freaked, and the promoters wouldn’t let me ride anymore because things were rapidly getting out of control. The floor was rushed by fans and riders, and some kid grabbed the laminate around my neck, strangling me until he got his souvenir. The flip fakie made the cover of five bike magazines, including

Go

, with a headline that read: “Sickest Trick Ever.”