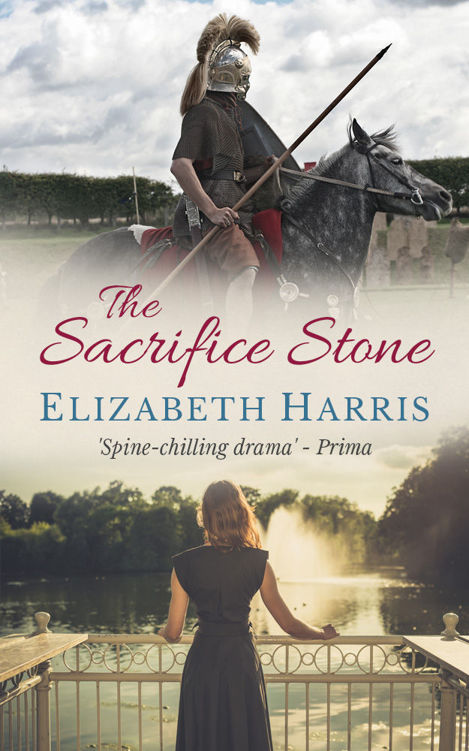

The Sacrifice Stone

Read The Sacrifice Stone Online

Authors: Elizabeth Harris

© Elizabeth Harris 1996

Elizabeth Harris has asserted her rights under the Copyright, Design and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

First published in 1996 by Harper Collins Publishers.

This edition published in 2015 by Endeavour Press Ltd.

For

Win

Skipper

,

an

armchair

traveller

,

First

Class

,

with

much

love

.

Table of Contents

GLANUM, AD 175

*

The moon was almost full, its brilliant light dimming the stars in the clear sky. On the lower slopes, the tall juniper trees cast long black shadows on the scrub-covered ground; higher up, where only the thorn bushes grew, the rocks lay bare beneath the night.

The warm earth, remembering the heat of day, gave off scents of dust and of herbs. The noise of the town had ceased, now that midnight was near and its good citizens all abed; no loudly stated opinions echoed from the forum, no sudden female laughter burst from the steps leading down to the sacred well. The small sounds of a dog’s bark, a slamming door, were too distant to make more than a momentary impact.

Deep silence covered the hillside: the land was asleep.

A soft breeze breathed down the narrow valley; the long shadows of the conifers wavered against the moonlit hillside.

As the movement ceased, a patch of shade detached itself and began to creep up the slope above the town. Behind it came another, and one more that flanked a shadow of a different shape.

The man, who had waited so patiently in the cramped space under the overhanging rock, watched. He could hear them, despite their efforts to be silent. One of the men was big and ungainly, and the exertion was making him pant. And the young bull, resentful at being led, perhaps in pain from the newly inserted ring through its nose, was giving snorts of anger.

He settled back against the rock. He would be there for a long time yet, he might as well ...

Suddenly he shot to his feet.

No

!

He swallowed the oath before he had made any sound, but the sight of the slim figure darting from tree to tree, tracking the leading group so skilfully that none of them would know it, made his heart race with fury.

For once in his life indecisive, he stood in front of the rock shelter, his thoughts racing.

Then, mind made up, he set off after the others.

*

High in the hills behind the town lay a fallen monolith, its ancient stone pitted and worn by the harsh sun and the strong winds of Provincia. The moonlight struck the long pale shape as if deliberately illuminating it; it looked like an altar.

Behind, in a shallow dell sheltered by the rocks into which it was built, was a small temple.

From the doorway the temple’s interior was dark, apart from the dim and steady light of a candle. The men emerging into the moonlight blinked as their eyes adjusted to the brightness.

The bull bellowed, once, twice, the furious sound so loud in the silence that the very rocks rang. Then anger changed to fear, and the bellow became a squeal which rapidly rose to a high note of pure hysteria.

Abruptly it stopped.

Another cry began, but one not made by any bull.

It was human.

The voice, made shrill by terror, grew louder and more piercing as panic rose. It was a sound to make the skin creep.

Then the nature of the scream changed, and the sharp tone fuzzed as it trailed off into a bubbling choke.

And the bright, moonlit stone of the monolith gradually darkened as the blood flowed across it.

‘You used to do that when you were a kid,’ Joe said.

‘What?’

‘Chew your hair when you were anxious.’

She didn’t care for the vaguely patronizing tone. ‘Well, you make me nervous.’ Damn! Instantly she regretted admitting to it.

‘Beth, I’m only asking you to map-read, for goodness’s sake. It’s me who’s having to cope with all this traffic, and driving on the wrong side of the road.’

He was right about the road — although since it was a motorway she couldn’t see that it made a lot of difference — but not about the traffic. Since coming off the boat at Calais a couple of hours ago, they’d probably seen scarcely more than a hundred vehicles. It was, after all, the small hours of the morning.

Once upon a time, Beth reflected, glancing down surreptitiously to check that it really was Reims they wanted and she hadn’t made a very early boob, Joe would have said ‘For God’s sake’, just like everyone else did. But now he was a theology student — a mature one to boot, and doing an MA — he’d ironed even minor blasphemies out of his speech. Since

The

Rector’s

Wife

, theologians were getting a better press — ‘They’re human, aren’t they, just like you and me?’ people would remark, often with slight amazement — but still, it was surprising how many of her girlfriends suddenly cancelled foursome dates in favour of prior engagements when she told them what Joe was studying.

Looking at it honestly, she had to admit that actually quite a few of the girlfriends lost interest after meeting Joe, not after finding out about the theology; it wasn’t what he did but what he was that seemed to put them off.

My brother, she thought, glancing across at him. Staring intently ahead, as if still trying to impress on her how noble he was being in taking on the perilous task of driving, he didn’t notice. I’ve known him all my life, we were pretty close when we were young, and even now, when we don’t get together all that often, I’m always glad to see him when we do. Only ... Only what?

She hesitated over answering the silent question. We’re at the very start of a three-week trip together, she thought ruefully, and maybe this isn’t the moment for me to be asking myself why my brother irritates me so much.

She decided to think positive. Three weeks in the South of France! Arles, the Camargue, and it won’t all be work, Joe’s absolutely promised we’ll have the occasional day off to find a lovely beach to lie on, with a picnic of bread, local cheese and wine, a jar of black olives and a couple of peaches. And it’ll be gorgeous down there now — late enough for all the holidaymakers to be long gone, but not so late that the weather’s turned unreliable.

When Joe had proposed that she accompany him on his research trip, she had given the matter only token consideration before saying yes. It wasn’t just the attractions of Provence that outweighed any doubts she had over spending three weeks with her brother, it was also what he was planning to research. He was writing the first major thesis of his course, and he had chosen to concentrate on early Christian martyrs, taking a contemporary view of the question of martyrdom and comparing it with the faith of the first centuries AD: the purpose of going to Arles was to investigate the legend of an obscure child saint who had apparently been killed by a Roman officer for refusing to make a sacrifice to the state gods of Rome.

Little Saint Theodore wasn’t going to be obscure for much longer: not only was Joe going to write his thesis — Beth smiled to herself at the thought that one insignificant paper presented in a small-town university was going to rock academia to its foundations — but, far more importantly, it was rumoured that a thirteen-year-old girl had seen a vision. She’d gone to pray in her village church, just outside Arles, taking Madonna lilies to lay before a statue of the Virgin. Stripped of all its trappings of religious mania — Beth reflected ruefully that she was probably more ruthless than most when it came to such stripping — the bones of the story seemed to be that the girl had seen the Virgin point to a plaster effigy of St Theodore, suggesting that the little boy was a worthier recipient of the flowers. The girl had prostrated herself before the boy’s statue, and he had smiled down on her, so touched at her gift that real tears had flowed down his cheeks, mingling with the blood issuing from the wounds of his martyrdom.

Beth had been almost sorry to read of the lurid details; until she was asked to believe the impossible, she had kept an open mind on the subject of the Roman officer and the child saint. Against her will — for she was imbued with twentieth-century cynicism — she had found herself touched at the idea of a small boy whose faith was so strong that, pathetically, death was preferable to betrayal of the gentle God he loved. And what a death — Joe had told her, not without a certain relish, that a common method of execution among the Romans was to cut the victim’s throat.

‘That’s what they did to St Theodore,’ he had explained, ‘and a miracle happened because, even though his head was almost severed from his body, he went on singing Ave Marias till someone found his remains.’

‘Like in “The Prioress’s Tale”,’ she had responded eagerly — she’d done

The

Canterbury

Tales

for O level, and it was always nice to be able to match Joe’s sagacity with a bull’s-eye of her own.

Joe sniffed. That’s just a story,’ he said dismissively.

‘And your Little Saint Theodore isn’t?’

He seemed to be taking his time about preparing the clincher, and she smiled to herself. ‘No, it isn’t. St Theodore really lived — you forget we’re talking of an era when history was recorded, so the details of his life can be proved. We know when he died, we can make an educated guess as to how. And there was certainly something miraculous concerning his death, because St Theodore was able to cure throat infections. There are heaps of well-documented cases, up till the early Middle Ages. And now this girl’s had her vision!’

He nodded as if to say, so there! But somewhere in his speech for the defence he had shifted his ground, moved from the written records of the administration-minded Romans to the gullible superstition of the medieval religious fanatic. Not to mention that of all the twentieth-century ones busy hurling themselves out of the woodwork. She was sorely tempted to probe, to ask exactly what he meant by well-documented, but she was only too aware what it would lead to: she would become more forceful as she edged him on to the ropes, he’d respond by getting lofty and sanctimonious — he’d once terminated a heated argument about abortion by stating that it was wrong because it wasn’t God’s will, slamming the door on her furious comment that it was typical of a male to resort to a higher authority when he was cornered — and she’d lose her temper. This time, assuming he hadn’t got as far as slamming the door, he’d greet her outburst by smiling condescendingly and remarking that women shouldn’t get involved in philosophical discussions, their emotional make-up was too fragile.

Joe, she reflected as the sign for ‘Reims Sud’ flashed by, had absorbed the doctrine of male supremacy that had ruled in the family home. In spades.

Her thoughts were interrupted: Joe said, ‘Do you mind if I put a tape on? If you’re not going to talk, I’d like some music.’

‘Carry on.’

She wondered if he’d consult her over what to play. He won’t, she thought, it’s a major concession that he’s asked if I mind in the first place.

She was right: he didn’t. Soon the car was filled with the calm, controlled sounds of a choir of monks singing plainsong. She almost laughed out loud; it’s not the music, she thought, controlling the impulse — that’s enchanting. It’s just — oh, God, it’s just Joe!

‘Hmmm, hmmm, hum,’ Joe chanted, singing along with the monks, slightly off-key. ‘This is the choir of St Nicetus’s monastery. It’s in a remote part of Hungary, they have nothing at all to do with modern civilization. Hum, hmmm.’

They’re canny enough to make a recording and sell it, she thought, amused at his determination not to see the proof of worldliness staring him in the face. Still, no doubt they give the proceeds to charity.

Joe’s humming soon ran out of steam, and, gratefully, she returned to her analysis of his character. Of course, he’s just like his father.

Our

father, she corrected herself. Our Father which aren’t in heaven, and, if there really is a heaven and any justice in the world, probably won’t ever get there. In fact, considering what the old sod is like, Joe’s really remarkably well balanced — it must be dear old Mum’s influence.

Her mother’s face shimmered in her mind’s eye, and she was filled with love. Is life any better for her now, with Joe and me away from home and the cause of all those rows no longer there? She doesn’t have to try to defend me any more — poor darling, not that she was ever very effective, you could tell her heart wasn’t really in it — and she can revert to being the dutiful wife who keeps house and keeps her views, if she has the temerity to possess any, to herself.

A scene from years ago filled her memory. Her mother had just dished up Sunday lunch, the beef slightly burnt because the vicar’s sermon had gone on ten minutes longer than it normally did. Joe — a sixteen-year-old Joe, all pimples, testosterone surges and dogmatic opinions — was holding forth about what he was planning to study in the sixth form, and how his long-term career prospects were shaping up. Waiting patiently until he’d finished — they’d eaten the first course by then and were starting on the cabinet pudding, also burnt — Beth ventured to say that her science teacher had recommended she seriously consider going on to do science A levels, as her work was outstanding.

Several unexpected things followed her apparently innocuous remark. Joe gave a disparaging snort and declared, despite the evidence he’d just been given to the contrary, that girls couldn’t do science. Her mother, pouring oil on the waters before they were any more than slightly rippled, said timidly, wouldn’t it be nicer for Beth to do something useful such as domestic science — and she knows I hate cooking! — or English, which would help towards being a secretary, or ...

Across the gentle voice came her father’s autocratic boom.

‘Your brother is quite right, Elizabeth. Science is unsuitable for a girl. Especially biology,’ he added enigmatically. He fixed her with a glare. ‘I would have thought’ — Beth’s heart sank as she recognized her father’s way of introducing some dictum which immediately became law — ‘that education to O level will suffice. Despite the opinions of your science teacher, whom I am sure is a conscientious enough woman in her way,’ — he sniffed to express his disapproval, and Beth didn’t dare point out that her science teacher was actually a man — ‘I see neither the need nor the wisdom of your continuing your scientific studies when you could be employed in some little job.’

She thought he’d finished. God, it was enough! But, after taking another mouthful of cabinet pudding and chewing it a thoughtful twenty times, he said, ‘And go to your room for your boastfulness in announcing that your work is outstanding.’

‘But —’

There wasn’t a but. In Beth’s father’s book, the man of the house made the rules and everyone else abided by them. Out of touch with modern ways, a man who had married too late, begotten children too late — even been born too late, for he was surely some forgotten relic of the Victorian days of his grandfather — he saw nothing amiss in sending a fourteen-year-old girl to her room for boastfulness.

And I wasn’t boasting, Beth thought, furiously punching her pillow, I was only repeating what Mr Thomas said.

I thought that was the end of it, that day. I hadn’t made my dream then, the only progress I’d made towards it was to recognize there was something I could do well and promise myself I’d work as hard as I could at it. Then along came good old Father, crushing out the flame when it was only just starting to flicker.

She had done what she was told for ten more years, leaving school after O levels to take a year’s shorthand and typing course. Mr Thomas had been quite right: although her grades for five of the eight subjects were only average, for physics, chemistry and biology she got ‘A’s. Mr Thomas had made a last-ditch attempt to persuade her to stay on; for the final time she’d explained she couldn’t — ‘for family reasons’, she’d said, and Mr Thomas, who had met her father on a parents’ evening, seemed to understand. Nevertheless, when he’d turned away, he’d looked as sad as if she’d been his own daughter.

The shorthand and typing course had been okay, and as soon as she’d got her certificate she started work; her first job was in an estate agent’s office, where, in addition to polishing her secretarial skills, she picked up quite a lot of information that was to stand her in good stead later, when she bought her first flat. After several years there, she’d worked for a firm selling folding bicycles, and when the short-lived craze died down found herself out of a job. The remarks over the Sunday lunch table became acerbic within a fortnight — her father left her in no doubt as to what he thought of offspring who expected to sponge off their parents when they were perfectly capable of earning their keep, which was somewhat hypocritical in view of the fact that Joe was then doing his first degree and wrote home repeatedly for extra funds, which were always dispatched immediately. Unable to find a permanent post — there was just nothing being advertised — Beth joined a temping agency.

Her father, predictably, disapproved. He’d seen something on TV about temps, and had got it into his head that they were universally flighty. For some inexplicable reason, he also thought they were all on the look-out for husbands. Beth, who couldn’t begin to see why a temp should be more desperate for marriage than the next woman, kept her peace and maintained a low profile.