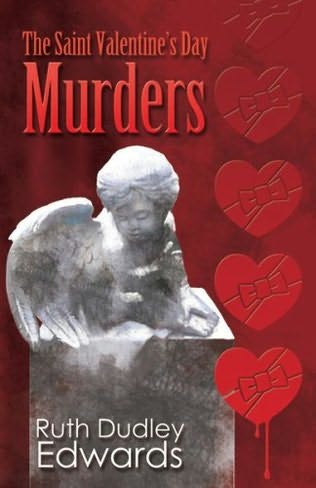

The Saint Valentine's Day Murders

Read The Saint Valentine's Day Murders Online

Authors: Ruth Dudley Edwards

Tags: #Fiction, #General, #Mystery & Detective, #Great Britain, #Mystery, #Detective and Mystery Stories, #Humorous, #Amiss; Robert (Fictitious Character), #Civil Service - Great Britain - Fiction, #Amiss; Robert (Fictitious Character) - Fiction, #Civil Service, #Humorous Stories

The Saint Valentine's Day Murders

Ruth Dudley Edwards

1984

Amiss and Troutbeck 02

A 3S digital back-up edition 1.0

click for scan notes and proofing history

Contents

|

Prologue

|

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

5

|

6

|

7

|

8

|

9

|

10

|

11

|

12

|

13

|

14

|

|

15

|

16

|

17

|

18

|

19

|

20

|

21

|

22

|

23

|

24

|

25

|

26

|

27

|

|

28

|

29

|

30

|

31

|

32

|

33

|

34

|

35

|

36

|

37

|

38

|

39

|

|

Epilogue

|

Also by Ruth Dudley Edwards

Corridors of Death

Robert Amiss, the young civil servant who is the hero of Ruth Dudley Edwards’s first book,

Corridors of Death,

has been seconded to a dead-end job in a recently privatized corporation. Struggling to keep his sanity in the midst of incompetence and farce, he is alarmed by the frustrations and tensions within the department, which are brought to a head by the arrival of Melissa, the lesbian separatist.

Who sends the poisoned chocolates on St Valentine’s Day? Henry Crump, the dirty old man? Or Tony Farson, the miser? Or Graham Illingworth, the gloomy DIY enthusiast? Or Bill Thomas, the bachelor who lives only for his garden? Or Tiny Short, the sixteen-stone rugger fanatic? Or someone on the fringes of this depressed group?

Amiss and his friend Superintendent Milton find themselves trying to assess motives in a grey suburban world where marital discord is rife and all feel cheated and trapped by life.

Elegantly and wittily written — and yet with serious undertones —

The Saint

Valentine’s Day Murders

is a worthy successor to the much-acclaimed

Corridors of Death.

First published by Quartet Books Limited 1984

A member of the Namara Group 27/9 Goodge Street, London W1P 1FD

Copyright© 1984 Ruth Dudley Edwards

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Edwards, Ruth Dudley

The Saint Valentine’s Day murders.

I. Title

823'.914 [F] PR6055.D/

ISBN 0-7043-2442-3

Typeset by M C Typeset, Chatham, Kent

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Mackays of Chatham Limited, Kent

To Jack and Marie Mattock

Prologue

February

‘The Department is offering you the opportunity of a lifetime.’

Amiss looked doubtfully at the expressionless face of his career manager. ‘But I had been hoping for a secondment to a real industry.’ And then, seeing from the stiffening across the desk that he had been tactless: ‘Of course, I’m not implying that British Conservation isn’t a proper commercial outfit. It’s just that it’s such a recent spin-off from the Department of Conservation that it can’t be operating like an ordinary firm.’

‘The British Conservation Corporation may have been set up with government funding,’ said his interlocutor coldly, ‘but its profit targets are such that it is required to be dynamic and competitive. You are not, I trust, suggesting that the presence within it of a number of ex-civil servants is likely to prove a hindrance to efficiency?’

Amiss felt his courage desert him. He wasn’t going to get anywhere with a wanker like this. ‘No, no. Of course not. It sounds very interesting.’

‘Good. That’s settled. You will take up a managerial job with the corporation at the beginning of May for a period of one year. Their Personnel Department will be in touch with you beforehand to give you details of the post allocated to you. In the meantime, they insist that you take a number of courses to fit you for this challenging work. It has been agreed that you will spend two months undergoing training in management, business studies and computing.’

Amiss reflected that it didn’t say much for Authority’s view of the intricacy of these sciences that he was supposed to mug them up just like that, but he kept his mouth shut and tried to look eager.

‘In addition. Immediately before taking up your duties with the BCC you will attend a full week’s induction course on its organization and responsibilities.’

Amiss was feeling a bit dazed, but he hadn’t forgotten the key question. ‘I will have Principal rank in the BCC, won’t I?’

‘Er… not quite.’

‘But that was the whole idea. You said weeks ago that my promotion would be confirmed if I were seconded.’

The face opposite stared at him bleakly. ‘The whole idea – as you put it – is to give you an opportunity to develop skills outside the service which will in the future be of use within the service. You already know that with the present government cut-backs your chances of finding a Principal post within the Department during the next eighteen months are negligible. In the BCC you will have a rank roughly on a par with – but rather better paid than – a Senior Executive Officer. I think the BCC has been extremely generous in agreeing to accept one of your comparative inexperience at such a responsible level. You should not run away with the idea that your good fortune in having worked for the Permanent Secretary entitles you to special consideration.’

Their eyes met. Amiss’s dropped first. ‘Oh, all right,’ he muttered weakly. ‘I’m sure I’ll find the year very rewarding.’

1

10 May

It was a chastened Amiss who set off for BCC headquarters on his first day of work. He was filled with doubts about his ability to perform adequately in an organization apparently so dedicated, so thrusting and so demanding of its staff. His confidence, already somewhat eroded by the bewildering succession of intensive courses, had fallen towards zero during his week of induction. The corporation was clearly no place for a gifted amateur. He had been singled out from among his fellow newcomers for many a diatribe about the importance of professionalism, single-mindedness and expertise. No man, it appeared, could hope to succeed in the BCC without years of practical experience advising industry on conservation. The Department of Conservation, the instructor had pointed out with an ill-concealed sneer, had to be there to deal with politicians, but its activities were only peripheral. It was the BCC – muscular and sinewy – that was single-handedly fighting the battle against waste in industry. Its research scientists were second to none; its advisory service was working flat-out to convert the factories of Great Britain to energy saving and reprocessing. In the five years since the corporation had been formed from a nucleus of Departmental scientists and administrators, it had been transformed into a profitable enterprise. Men of commerce had been recruited; cost effectiveness was the watchword; growth was unstoppable. There were now over 1,000 employees – whizz kids to a man. ‘The BCC,’ said the instructor without the glimmer of a smile, ‘is where it is all at.’ There still remained within Amiss’s battered psyche some small corner of scepticism. After all, there was no getting away from the fact that the instructor was a prat of the first order, and probably also a hyperbolic prat. His apprehensions about the new job were disproportionate. What was it the behavioural scientist had said during that seminar on Stress Situations? – that natural fears about a new job should be counteracted by listing to oneself one’s areas of competence. Well, if he was rather lacking in technical skills and experience, at least he was a finely trained flanneler on matters about which he knew nothing.

What was the new job, anyway? It was hardly a sign of superhuman efficiency that the Personnel Department hadn’t told him anything about it until the previous Friday. Appeals for information over the preceding weeks had been met with procrastinating mutters. Even now, all he knew was that he was to present himself at 9 a.m. to a Mr D. Shipton at the headquarters building in south London, when all would be revealed. Dammit, even the civil service usually gave people more advance notice than that.

He struck out bravely from the tube station, looking about him alertly in the intervals between consulting the map. What an odd place to site the headquarters of a major company, he thought. Grime was the district’s main feature. There were miserable rows of depressed housing, interleaved with unpainted chip shops, dingy cafes, fly-by-night surplus stores, grocery shops with a range suited to the needs of octogenarians of a conservative disposition, greengrocers that had never heard of any fruit or

légume

more exotic than a banana. It was only fitting that his long walk through the main streets should be taken in the grey light, chilling breeze and insidious rain that heralded the beginning of an English May.

His sense of relief on arriving at the street that boasted the BCC was swiftly overtaken by a wave of desolation. Ahead of him lay a vast and largely undeveloped wasteland. Not a tree graced the barren acres, in the centre of which had been erected an apologetic-looking high block dominated by slabs of plate glass tastefully set off by yellowish-grey concrete. Even by the standards of contemporary British architecture, this building was a notable bummer. The architect had clearly been a man of unusual modesty, terrified lest he allow any signs of individuality in the design which might make it possible to identify him.

The rain was intensifying, so Amiss ran towards the entrance for cover. The inside wasn’t quite so bad. Someone had made a bit of an effort with a paint pot and a few plants. Perhaps it wasn’t the fault of the BCC that they had been cursed with this God-forsaken hole: it had probably been foisted on them by a malevolent decision from what was humorously known as the Department of the Environment. The receptionist, too, was agreeable enough, even if it took her a moment or two to remember the whereabouts of Mr D. Shipton and despatch Amiss to the fifth floor.

Shipton’s office had a strangely familiar aura. It could have been the room of any middle ranking civil servant – the same off-white walls, bulk-purchase teak furniture and regulation coat stand. Shipton himself was at the far end of the room, lying rather than sitting in his leather chair, a mass of supine fat clothed in shiny navy blue. As Amiss introduced himself, Shipton’s right arm waved him lethargically towards the armchair. He looked like a man about to expire from exhaustion. Amiss wondered if he was recovering from jet-lag or all-night negotiations. That tired old frame might have been sacrificing its health and strength in the pursuit of a higher profit margin.

‘Tell me about yourself,’ said Shipton uninterestedly. Amiss obligingly ran through an account of his civil service career, and then, seeing no flicker of reaction on the flabby face in front of him, tore into a summary of what he had studied on his recent training marathon. He looked hopefully at Shipton. Nothing. Shipton moved suddenly, but it was only to make an ill-disguised attempt to smother a yawn. Amiss didn’t give up, but embarked on a peroration about his enthusiasm for this new challenge and his determination to work his balls off in the service of the corporation. This time he got Shipton’s attention: an expression of mild bewilderment spread across the crumpled features. ‘Fine,’ said Shipton. ‘Fine, fine.’