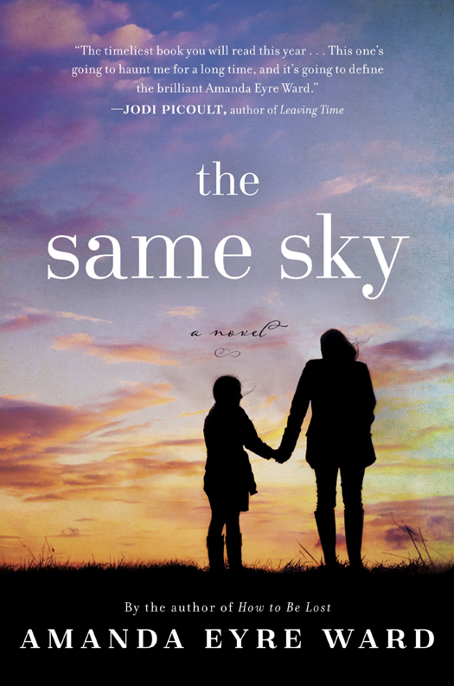

The Same Sky

Authors: Amanda Eyre Ward

Tags: #Fiction, #Contemporary Women, #Literary, #Sagas

The Same Sky

is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. The author’s use of the names of real places, events, or public figures are not intended to change the entirely fictional character of the work. In all other respects any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2015 by Amanda Eyre Ward

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Ballantine Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

BALLANTINE and the HOUSE colophon are registered trademarks of

Random House LLC.

ISBN 978-0-553-39050-6

eBook ISBN 978-0-553-39051-3

Jacket design: Laura Klynstra

Jacket photograph: © Lee Avison/Arcangel Images

v3.1

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Dedication

Acknowledgments

Other Books by This Author

About the Author

1

Carla

M

Y MOTHER LEFT

when I was five years old. I have a photo of the two of us, standing in our yard. In the picture, my mother is nineteen and bone-thin. The glass shards on the top of our fence glitter in the afternoon sun and our smiles are the same: lopsided, without fear. Her teeth are white as American sugar. I lean into my mother. My arms reach around her waist. I am wearing a cotton dress, a dress I wore every day until it split along the back seam. When the dress fell apart, my grandmother, Ana, stitched it back together with a needle and thread. Finally, my stomach pushed against the fabric uncomfortably and the garment was just too short. By that time, my mother was in Texas, and for my sixth birthday she sent three new dresses from a store called Old Navy.

When I opened that box, it seemed worth it—growing

up without being able to touch my mother, to press my face against her legs as she fried tortillas on the gas stove. One dress was blue-and-white striped; on one, a cartoon girl ice-skated wearing earmuffs; the last was red. My friends with mothers—Humberto, Maria, Stefani—they stared at my outfits when I wore them to school. Maria could not take her eyes off the picture of the girl on my dress. “She’s ice-skating,” I said.

“Your mother?” said Humberto, scratching at his knee. Though Humberto was always covered in mud and didn’t wipe his nose, I loved him and assumed we would be married in due time.

“Probably, yes, her too,” I said, lifting my chin. “But I meant the girl on my dress. See? She wears earmuffs and gloves. Because it’s cold. And the ice skates, obviously.”

“Ice is frozen water, but a lake of it,” added Stefani, whose mother had been my mother’s best friend. Only my mother had been brave enough to leave, once my grandmother had saved enough for the

coyote

.

My mother sent money regularly and called every Wednesday at 12:45 p.m. Wednesday was her day off from working in the kitchen of a restaurant called Texas Chicken. I imagined her wearing a uniform the color of bananas. There was a movie we had watched standing outside the PriceSmart electronics store where an actress with red hair wore a banana-colored uniform and a tidy waitress hat, so when my mother described her work, I dressed her in this outfit in my mind. My mother told me her feet hurt at the end of her shift. My feet hurt, as well, when I wore the

high-heeled shoes she’d sent. I needed shoes for running, I told her, and not three weeks later, a package with bright sneakers arrived.

There just wasn’t much for any of us in Tegucigalpa. We lived on the outskirts of the city, about a twenty-minute walk from the dump, where the older boys and men from our village worked, gathering trash that had value. Humberto’s older brother, Milton, left early in the morning. In the dark, he returned, his shoulders low with exhaustion and his hair and skin holding a rancid scent. Still—and to me, inexplicably—he had girlfriends. Though I had imagined what it would be like to kiss almost every boy in our village, I never closed my eyes and pictured Milton’s lips approaching—it seemed impossible to want to be close to someone who smelled so bad. He was handsome, however, and supported his family, so there was that.

My grandmother took in laundry, and we always had enough food, or most of the time. Mainly beans. I had twin brothers who were babies when our mother left and were starting to walk around uneasily when I turned six. They had a different father than I did, and none of our fathers remained in our village. Who knew if they were alive or dead and anyway, who cared.

This was how it was: most days our teacher came to school and some days he did not. When he had not come for three days, Humberto and I decided to go and find him at his house. We did not have bus fare and so we walked. We passed the city dump and watched the birds and the men and the boys. We split an orange Humberto

had stolen from the market. We plodded through the hot afternoon, and around dinnertime (if you had any dinner) we reached our teacher’s address.

The front door was open. Our teacher and his wife were dead, lying next to each other on the kitchen floor. The robbers had taken everything in the house. Our teacher, like me, had a mother in America, in Dallas, Texas, a gleaming city we had seen on the television in the window of the PriceSmart electronics store. The point is that our teacher had many things—a watch, alarm clock, boom box, lantern. Luckily, our teacher did not have any children (as far as we knew). That would have been very sad.

Humberto cried out when he saw the bodies. I did not make a sound. My eyes went to my teacher’s wrist, but his watch was gone. His wife no longer wore her ring or the bracelet our teacher had given her on their one-year anniversary. The robbers had taken our teacher’s shoes, shirt, and pants. It was strange to see our teacher like that. I had never seen his bare legs before. They were hairy.

Humberto and I walked home. We were not allowed to be out after dark, so we walked quickly. We wondered whether we would get another teacher. Humberto thought we would, but said he might stop going to school and start going with his brother to the dump. They needed more money. They had not had dinner in two nights, and he was hungry.

“If you smell like your brother,” I said, “I cannot be your girlfriend anymore.”

“Are you my girlfriend?” said Humberto.

“Not yet,” I said. “Not ever, if you smell like Milton.”

“When?” asked Humberto.

“When I’m eleven,” I told him.

He walked ahead of me, kicking the dirt. He shook his head. “I’m too hungry,” he said finally. “And that’s too long.”

“Race you,” I said. As we passed the dump, the birds shrieked: awful, empty cries. Yet the air on my skin was velvet, the sky magnificent with stars.

“Go,” said Humberto. We ran.

2

Alice

J

AKE AND I

weren’t sure what to do about the party. Benji had sent out an e-vite to all our friends and the whole Conroe’s BBQ staff before Naomi changed her mind about giving us her baby, and what else were we going to do with the afternoon? Just not show up? Just stay home and stare at Mitchell’s empty crib? (An aside: it was also possible that Mitchell was no longer named Mitchell. Naomi might have changed her mind about that as well.) In short, we went to Matt’s El Rancho on South Lamar.

Benji had gone all out. It was fantastic: a cake with blue frosting, baby presents piled high. There were margaritas and nachos, beef

flautas

and

queso flameado

. Jake ordered tequila shots like the old days. For about twenty minutes there was small talk, and then Lucy DeWitt said, “Well? Where

is

the little cutie?”

“Oh, Christ,” I said. “Well, it didn’t work out, in the end.”

Jake raised his arm to signal the busboy, pointing at our empty shot glasses. “

Dos más

,” said Jake.

“Oh, honey,” I said, putting my hand on Jake’s shoulder and looking at the busboy apologetically. It was offensive to assume he didn’t speak English, and also offensive to speak Spanish as badly as Jake did. I didn’t speak Spanish at all, but I was going to immerse myself some summer soon.

“More tequila?” said the busboy.

“Yes, please,” I said.

Jake said,

“Sí, sí.”

“What didn’t work out?” said Benji, his brow furrowed. “What do you mean, Alice?”

“The birth mother has forty-eight hours to change her mind,” explained Jake. “And our … and we …” Jake’s eyes grew teary, and he put his palm over his face. I stared dully at the burn scar on his thumb.