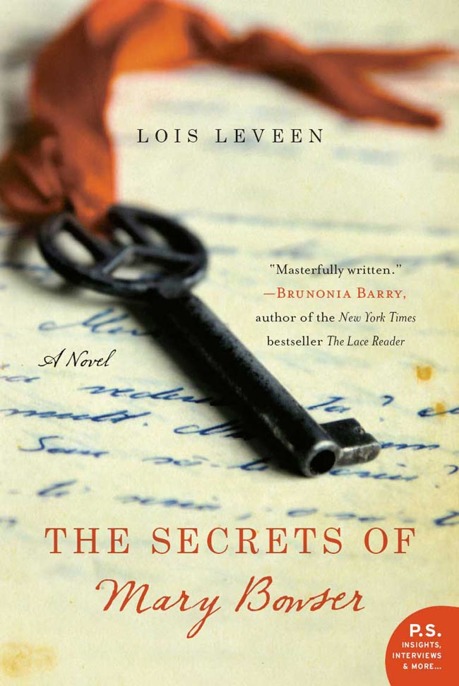

The Secrets of Mary Bowser

Read The Secrets of Mary Bowser Online

Authors: Lois Leveen

Tags: #Fiction, #General, #Freedmen, #Bowser; Mary Elizabeth, #Biographical, #Biographical Fiction, #United States, #United States - History - Civil War; 1861-1865 - Secret Service, #Historical, #Espionage, #Women spies

The

Secrets of Mary Bowser

L

OIS

L

EVEEN

If the whole of history is in one man, it is all to be explained from individual experience. . . . Each new fact in his private experience

f

lashes a light

o

n what g

r

eat bodies of men have done, and the

c

rises of

h

is life r

e

f

e

r to national cri

se

s.

—R

ALPH

W

ALDO

E

MERSON

, “H

ISTORY

,” 1841

Who shall go forward, and take off the reproach that is cast upon the people of color? Shall it be a woman?

—M

ARIA

S

TEWART

, “L

ECTURE

D

ELIVERED

AT THE

F

RANKLIN

H

ALL

, B

OSTON

,” 1832

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Epigraphs

Author’s Note

Prologue

BOOK ONE: Richmond 1844 –1851

One

Two

Three

BOOK TWO: Philadelphia 1851–1859

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

BOOK THREE: Richmond 1861–1865

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-one

Twenty-two

Twenty-three

Twenty-four

Twenty-five

Twenty-six

Twenty-seven

PS AUTHOR INSIGHTS, EXTRAS & MORE ...

Reader’s Guide

Historical Note

The World of Mary Bowser: Q&A with Lois Leveen

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Advance Praise for

The Secrets of Mary Bowser

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

T

his novel tells the story of a real person, Mary Bowser. Born a slave in Richmond, Virginia, Mary was freed and educated in the North but returned to the South and became a Union spy during the Civil War. Like many ordinary people who choose what is right rather than what is easy, she did extraordinary things.

Few details about Mary Bowser are known today. In the nineteenth century, little effort was made to record the daily lives of most slaves, free blacks, or women of any race. The scant facts about Mary Bowser that survive cannot tell us what we most want to know: What experiences in freedom would make her risk her life in a war she couldn’t be sure would bring emancipation? How did this educated African American woman feel, subjecting herself to people who regarded her as ignorant and even unhuman? How did living amid the death and destruction of America’s bloodiest war affect her?

The Secrets of Mary Bowser

interweaves historical figures, factual events, even actual correspondence and newspaper clippings, with fictional scenes, imagined characters, and invented dialogue, to answer these questions. Like Ralph Waldo Emerson, who lived at the same time as Mary Bowser (and who, in the style of the period, often said

man

when today we would say

person

), I believe that the crises of an individual life can shed light on national crises. The novel tells the story of one woman’s life—but it also tells the story of a nation torn apart by slavery, and brought back together by the daily bravery of countless people like Mary Bowser.

M

ama was always so busy. Busy tending to Old Master Van Lew and Mistress Van Lew, Young Master John, Miss Bet. But she was never too busy to riddle me. She said it was the first kind of learning she could give me, and the most important, too. Be alert, Mama meant. See the world around you. Find what you seek, because it’s already there.

“I spy with my little eye, where the bird goes when he doesn’t fly,” Mama said one mid-day, her words floating on the Richmond heat as we carried empty cookpots through the yard to the kitchen.

I sing-songed the riddle to myself, eyes half closed against the bright Virginia sun. What could she mean, with no birds in sight? Then I spotted it, set in the crook of the big dogwood.

“Oh, Mama, a bird’s nest!”

But Mama frowned. “I made a rhyme to riddle you, Mary El. You’re old enough to rhyme me back your answer.”

Whenever Mama said

you’re old enough,

it meant something new was coming. Something hard I had to do, no matter what—cleaning all those fireplaces, polishing the silver, helping her serve and clear the Van Lews’ meals. Old enough was never good news yet. And now old enough was ruining our favorite game.

I pouted for a bit, until Mama said, “No new riddle, until you answer that one proper.”

I wanted the next riddle so bad, the words burst out of me. “Up in the tree, that little nest, is where birdie goes when he wants a rest.”

Mama smiled her biggest smile. “A child of five, rhyming so well.” She set her armload of iron pots down, scooped me up, and looked to the sky. “Jesus, I know my child ain’t meant for slavery. She should be doing Your work, not Marse V’s or Mistress V’s.”

She kissed me, set me back on the ground, and picked up the cookpots again. “But meanwhile, I got to do their work for sure.”

Mama’s gone now. Though she worked as a slave all her life, she saw me free. She even put me onto the train to Philadelphia so I could go to school.

But a decade up North taught me about being bound in a different way than all my years in slavery ever did. Living free confounded me more than any of Mama’s riddles, until I puzzled out the fact that I could never truly savor my liberty unless I turned it into something more than just my own.

Once I realized that, I knew I had to come back to Virginia. Knew I was ready to take up the mantle of bondage I was supposed to have left behind. Except instead of some slave-owning master or mistress, it’s Mr. Lincoln I’m working for now.

Mama, your little girl is all grown up, and still playing our best game. I am a spy.

M

ama and I woke early, put on our Sunday dresses, and stole down all three sets of stairs from the garret to the cellar, slipping out the servants’ entrance before the Van Lews were even out of bed. We walked west down Grace Street, turning south past the tobacco factories to head toward Shockoe Bottom. The Bottom was nothing like Church Hill, where the Van Lew mansion sat above the city. Buildings in the Bottom were small and weather-worn, the lots crowded with all manner of manufactories and businesses. I held tight to Mama’s hand as we ducked into a narrow passageway between two storefronts along Main Street.

Papa stood tall on the other side of the passage, same as every Sunday, waiting for us in his scraggly patch of yard. As soon as he caught sight of me and Mama, a smile broke across his face like sunshine streaming through the clouds. He hugged and kissed us and then hugged us some more, looking me over like I’d changed so much since the week before that he feared he might not recognize me.

I may have changed, but he never did. My papa was so lean and strong, his muscles showed even through his Sunday shirt. His rich skin shone with the color and sheen of the South American coffee beans that made Richmond importers wealthy. Large brown eyes dominated his narrow face, the same eyes I found staring back at me whenever I passed the looking glass in Mistress Van Lew’s dressing room. What a strange and wonderful thing, to see a bit of Papa in my own reflection. All the more delightful when I pestered Mama with some peevish five-year-old’s demand and she chided, “Don’t look at me with your papa’s eyes.” Mama’s complaint told me that I was his child as much as hers, even during the six days a week we spent apart from him.

Standing beside Papa, Mama seemed small in a way she never did when she bustled about the Van Lew mansion. Although she was not a heavy woman, she was fleshy in a way Papa was not. Her skin was even darker than his, so deep and rich and matte that whenever I saw flour, I wondered that it could be so light in color yet as sheenless as Mama’s skin. Her brow and eyes curved down at the outside edges, making her seem determined and deliberate, whether her mouth was set straight across, lifted in one of her warm smiles, or, as was often the case, open in speech.

But for once, Papa was talking before Mama. “About time you ladies arrived. We got plenty to get done this fine morning.” Papa spoke with the soft cadence of a Tidewater negro, though he hadn’t seen the plantation where he was born since he was just a boy, when his first owner apprenticed him to Master Mahon, a Richmond blacksmith.

Mama’s voice sounded different from Papa’s, as sharp as though she and Old Master Van Lew had come from New York only the day before. “What can we have to do at this hour on a Sunday?”

“High time we return all that hospitality we been enjoying at the Bankses. I stopped over there on my way home last evening, invited them to come back here with us after prayer meeting.”

“That whole brood, over here?” Mama eyed Papa’s cabin. The four-room building had two entrances, Papa’s on the left, and the one for Mr. and Mrs. Wallace, the elderly free couple who were his landlords, on the right. Even put together, Papa’s two rooms were smaller than the attic quarters where Mama and I slept in the Van Lew mansion or the summer kitchen where the cook prepared the Van Lews’ meals. One room had but a fireplace, Papa’s meager supply of foodstuffs, and a small wooden table with three unmatched chairs. The other room held his sleeping pallet, a wash-basin set on an old crate, and a row of nails where he hung his clothes. The walls were unpainted, outside and in, the rough plank floors bare even in winter. The only adornments were the bright tattersall pattern of the osnaburg curtains Mama had sewn for the window and the metal cross Papa had crafted at Mahon’s smithy.

The way Mama frowned, I could tell what she was thinking. Broad and tall, Henry Banks was a large presence all by himself, a free colored man who risked enslavement to minister to the slaves and free negroes who gathered each week in the cellar of his house. A two-story house big enough to accommodate him, his wife, and their six children. On those Sundays when Mama, Papa, and I were invited to stay after prayer meeting for dinner with their family, I savored the chance to amuse myself among all those children. So though Mama frowned at Papa, I was delighted to hear that the whole pack of youngsters was coming over today.