The Shadow Year (23 page)

Authors: Hannah Richell

‘Goodnight then,’ he says, switching out the light and settling onto the creaking bed.

Lila breathes a silent sigh of relief. ‘Goodnight.’

Silence fills the darkness.

‘Lila . . .’

‘Yes?’

There is a pause. ‘Nothing.’

She holds her breath but Tom remains silent. ‘Tomorrow will be a better day,’ she says eventually, ‘I promise.’ But he must be asleep already because he doesn’t reply.

‘Lila!’ Tom is shaking her in the dark. ‘Lila, wake up.’

‘What?’ she asks. ‘What is it?’ Her heart hammers wildly in her chest.

‘You were screaming.’

‘I was?’ She props herself up on one elbow, tries to focus on the outline of him in the darkness.

‘Yes.’

‘Oh,’ she says, putting a hand to her sweaty brow, ‘I was.’

‘Are you OK?’

She thinks for a moment, tries to calm her thudding heart. ‘I’m OK. It was just a dream.’

‘You frightened the living daylights out of me.’

‘Sorry.’

‘It’s OK.’ He hesitates, then sits down next to her and puts his warm hand on her shoulder, strokes the curve of her neck with his fingers. ‘What were you dreaming about?’

Lila swallows. ‘The fall.’

‘Oh.’ In the darkness she can see his head droop slightly. ‘Do you dream about it much?’

She nods.

‘Have you remembered anything new?’

‘It’s strange. Tiny fragments are coming back to me but there’s still this huge hole. Every night now it’s the same. I’m in my bedroom, trying on clothes. The sun is shining through the window. I look in the mirror.’ She swallows again. ‘That was all I could remember for a long time but there’s a little more now.’

‘What?’ asks Tom.

‘My memory jumps – like a stuck record – and it’s the strangest thing . . .’ She hesitates. ‘You see, I’m

running

down the landing at home and I reach the top of the stairs,’ she swallows, ‘but then I’m just falling – plunging into darkness.’

Tom is quiet for a moment. ‘Perhaps you’re confusing dreams with memories?’

She shakes her head. ‘No. It feels real.’

Tom reaches out to smooth a loose strand of hair away from her face. ‘Don’t you find this place spooky, out here on your own?’ he asks quietly.

‘Spooky how?’

‘I don’t know.’ He shivers in the cold night air. ‘It’s hard to explain. There are just some places that feel . . . that feel as though something has

happened

there. I think this cottage might be one of them.’

She understands: the logs in the basket . . . the bullet hole in the kitchen . . . the abandoned possessions . . . the inexplicable sensation of being watched; ever since she arrived at the cottage she hasn’t been able to shake the feeling that the old cottage has been trying to tell her something.

‘Don’t you find it unnerving?’ he persists.

‘No,’ she lies, ‘not really.’

He sits with her a while longer, stroking her hair until sleep’s creeping tendrils wrap themselves around her once more. ‘Tom,’ she murmurs.

‘Yes, Lila.’

‘Go back to bed.’

‘OK, Lila.’

It is her suggestion to hike up onto the moorland the next morning. It has finally stopped raining and looking out over the blue eye of the lake, she is desperate, suddenly, to offer Tom a different side to her life in the valley. She wants to show him how beautiful it can be there, how peaceful and still. ‘Come on, it’s your last day. You should get a good look at the place.’

‘But what about the painting? I thought you wanted my help?’

‘It can wait. Let’s go, while there’s a break in the weather . . .’

Tom nods. ‘Come on then,’ he says, the slightest challenge in his voice, ‘show me what you

love

about this place.’

At first she thinks she’ll lead him through the woodland circumnavigating the lake, where the trees shiver in their near-leafless state and throw long, spiny shadows out over the water, but then she remembers the rain and how boggy it will be, so instead she turns to strike out across the meadow and up the steep track leading over the hills. The higher up they go the more stripped-back the land becomes until soon they are walking across open moorland. For a while they walk in silence, their arms swinging at their sides, a metre or so apart all the way.

‘Where are we going?’ he asks.

‘I don’t know,’ she admits, unwinding her woollen scarf, letting it dangle from her hands, ‘just rambling.’

He nods. ‘OK.’

Eventually they come to an old stone wall. ‘Shall we sit for a bit?’ she asks.

They perch together on the weathered wall and gaze out at the vast sky. ‘Isn’t it beautiful?’ she says. ‘Look, that must be the cottage, all the way down there.’ She points to a thin plume of smoke rising in the distance, evidence of the fire they have left smouldering in the grate. ‘Don’t you feel a million miles away from London right now? From the rest of the world?’

‘Yes,’ says Tom, but the way he says it doesn’t make it sound like a good thing.

Lila wonders if now is the time for them to talk, up here, in the clean air, away from everything that is familiar or real. Geographical change is good, she knows, it’s a distraction, but she’s also coming to understand that Tom is right; she can’t outrun her grief. As much as she wishes she could leave it far behind, like a sprinter taking off from a start line, she sees that no matter how fast she runs, she is on an oval track, and she only ever comes back to the beginning, back to the pain she hasn’t yet worked out how to live with. So perhaps she should discuss the baby with him. Perhaps she should discuss her strange and disturbing dreams in more detail, but every time she thinks to bring it up she loses her nerve. The only thing it seems Tom wants to talk about is

when

she will give up the cottage and return home.

He sighs and shifts on the wall next to her. ‘It’s so remote, Lila. I’m worried about you, that’s all.’

‘I’m OK. I like the space . . . the freedom. I like waking in the morning with that ache in my muscles that tells me I’ve done a real day’s work.’

‘And

I

like waking in our bed with you beside me.’

‘I just don’t want to be there right now. I can’t explain it.’

‘You mean you don’t want to be with

me

right now?’

‘No. I didn’t say that. It’s not you. It’s just this feeling of . . . of—’

‘Of what, Lila?’

‘I can’t explain.’

‘Well try.’

Lila sighs.

‘It wasn’t my fault,’ says Tom eventually, so quietly she almost doesn’t hear.

‘I know that,’ says Lila, shocked. ‘Why would I think losing Milly was

your

fault?’

He shrugs. ‘Sometimes it feels as though you’re blaming me.’

Lila is baffled. The only person she has been blaming in all of this is herself. ‘I’m not blaming you . . . but it might help if you talked to me about it . . . if you opened up a little. Sometimes

I

feel as though I’m the only one who’s grieving for her.’

Tom shakes his head. ‘How can you say that?’

‘Well, for one thing you could talk about her . . . you could say her name.’

Tom stares at her.

‘You never say it. Milly: you never say your daughter’s name.’

‘I do.’

‘No,’ Lila shakes her head firmly, ‘you don’t.’

Tom is silent, his head lowered. When he speaks next his voice is so quiet she has to lean in close to hear him. ‘I say it in my head . . . sometimes it feels like she’s

all

I have in my head.’

She nods, understanding, but still can’t help noticing he hasn’t said their daughter’s name out loud. ‘Look,’ she says after a while, softening her voice, ‘why don’t you take some time off work and come and stay here for a little while? Two pairs of hands will be much quicker than one. It will be a chance for us to be together. It could be good for us.’

‘You know I can’t just drop everything.’ He runs his hands through his hair and then gazes out across the horizon. ‘It’s not a good time at work.’

‘I just think—’

But he cuts her off. ‘Lila, I don’t know what’s going on with you but we can’t go on like this. Come home, please. I need you.’

She looks at him, stung. He doesn’t know what is going on with

her

? Does he not remember what they went through – together – just a few short months ago? The agony of the labour, the terrifying sight of their baby – too small – too pale – being whisked away by the nurses and hooked up to a scary array of tubes and machines in the neonatal unit. Does he not remember the tears, the bruises, the heartache of losing their daughter? The loss of all they’d dreamed of? Of course the physical signs of the pregnancy and the fall have gone: her body has shrunk back in on itself, the cuts and bruises have healed . . . but her heart . . . her heart is another thing entirely, still damaged, still broken. Does he really not remember

any

of that?

‘And I need this,’ she says finally. She looks across at him, tears in her eyes, imploring him to try to understand, but he keeps his gaze fixed on the blank sky overhead, his eyes trained on a kestrel wheeling and turning on a thermal high above their heads. ‘Tom?’

He doesn’t turn and staring at him she feels an anger spiral up from deep inside.

This

is their problem, she thinks, this disconnect they just can’t seem to get beyond.

Leaving him on the wall, she jumps down, turns on her heel and stomps off across the boggy terrain, the cold wind drying the tears in her eyes before they can spill down her cheeks. Let him find his own way back to the cottage, Lila thinks; she doesn’t care.

When they say goodbye later that evening, a small part of her is relieved to see him go. It hasn’t been the romantic reunion either of them had been hoping for. With Tom there, Lila has seen the place differently again, through his eyes, noticing every flaw and every imperfection, every job that needs doing, big and small; but rather than make her want to leave, it has fired up that stubborn part of her that won’t let it go. It has made her impatient to keep going, to fix things before she can lose heart.

She heads upstairs to the bedroom, eyes the camp bed where Tom lay just a few hours before. She reaches for his blanket and folds it into a neat square then perches on the bed frame and gazes, unseeing, at the dusty old fireplace across the other side of the room. She can feel her grief there with her still; like a well-worn garment that she has unpacked from her bag, shaken out and hung neatly on the clothes rail in the corner; a permanent, physical fixture hanging silently, waiting for her there no matter where she goes.

She gazes into the empty hearth and wonders how on earth she and Tom will ever reconnect across the chasm of their grief. She churns it over and over in her head until her mind turns outwards and her eyes begin to focus on a strange shadow upon the brickwork of the chimney breast. It’s probably just soot but she moves across the room and reaches out to touch the stone with her fingertip. The brick slips slightly and she sees that if she pulls a little she can remove it completely from where it is lodged. She tugs on it gently and the brick comes away in her hand, and there, beneath it, is a folded piece of paper, grey with dust and grime.

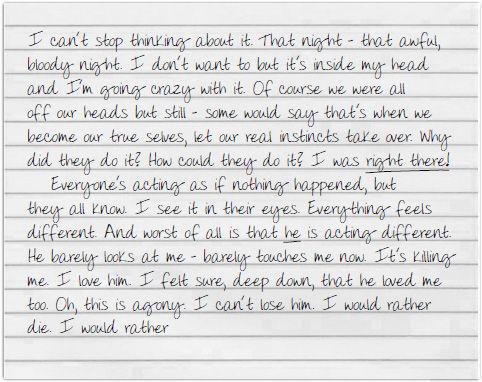

Quickly, she unfolds it and reads the first words of a handwritten scrawl.

I can’t stop thinking about it

. . . it begins.

Lila feels her heart begin to hammer in her chest. She thinks about the funny mural in the other room, the bullet hole downstairs, the pile of junk waiting to be burned at the top of the garden and then looks back to the piece of paper in her hand. Somebody was here. Somebody committed these words to paper and stashed them behind this stone. The goose bumps are back on her arms. She glances around, trying to rid herself of the echo of Tom’s words spoken in the very same room only hours earlier:

something happened here

. She shakes her head and then, with trembling hands, she smooths out the crumpled sheet of paper and begins to read.

1980

‘Kat!’

Kat slams the pen down and slides the notepad she has been scribbling on beneath the bedclothes.