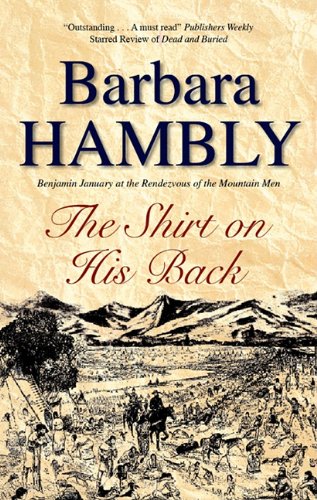

The Shirt On His Back

Read The Shirt On His Back Online

Authors: Barbara Hambly

The Shirt On His Back

Barbara Hambly

This

first world edition published 2011

in

Great Britain and the USA by

SEVERN

HOUSE PUBLISHERS LTD of

9-15

High Street, Sutton, Surrey, England, SMI 1DF.

Trade

paperback edition first published

in

Great Britain and the USA 2011 by

SEVERN

HOUSE PUBLISHERS LTD.

Copyright

© 2011 by Barbara Hambly.

For

Victoria

Table of Contents

The

third time that day that Benjamin January walked over to the Bank of Louisiana

and found its doors locked, he had to admit the truth.

It

wasn't going to reopen.

The

money was gone.

Admittedly,

there hadn't been much money in the account. Early the previous summer he'd

taken most of it and paid off everything he and Rose still owed on the big

ramshackle old house on Rue Esplanade, and

thank God,

he thought,

I had the wits to do that

. . .

Even

then, there'd been rumors that the smaller banks, the wildcat banks, the

private banks all over the twenty-six states were closing. Months before the

election last Fall the President's refusal to re-charter the Bank of the United

States had begun to pull down businesses along with the banks, and at meetings

of the Faubourg Treme Free Colored Militia and Burial Society

or

less formal get-togethers with his friends after playing all night for the

white folks at some Mardi Gras ball - January had frequently asked: what the

hell did the Democrats think was going to happen, when they knocked the

foundations out from under the only source of stable credit in the country?

Not

that it was any of January's business, or that of his friends either. As

descendants of Africans, at one remove or another - though January's mother

loftily avoided the subject not one of them could vote. And in New Orleans, by

virtue of its position as Queen of the Mississippi Valley trade, the illusion

of prosperity had hung on longer than elsewhere.

Still,

standing in the sharp spring sunlight of Rue Royale before the shut doors of

that gray granite building, January felt the waves of rage pass over him like

the wind-driven crescents of rain on the green face of a bayou in hurricane

season.

Rage

at the outgoing President - a fine warrior when the

country

had needed a warrior and a hopelessly bigoted old blockhead with a planter's

contempt for such things as banks.

Rage at the

whites who saw only the war hero and not the consequences of letting

land-grabbers and shoestring speculators run the country for their own profit.

Rage at the laws

of the land, that wouldn't let him - or anyone whose father or grandparents or

great-grandparents back to Adam had hailed from Africa - have the slightest

voice in the government of the country in which they'd been born, regardless of

the fact that he, Benjamin January, was a free man and a property owner . . .

Artisans like his brother-in-law Paul Corbier, merchants like Fortune Gerard

who sat on community boards, his fellow musicians and the surgeon who'd taught

him his trade of medicine, and all those others who made up his life, were free

men too, had been

born

free men and had fought a British invading force in order to stay that way . . .

And rage at

himself - the deepest anger of all as he turned his steps back along Rue Royale

toward home. For not taking every silver dime out of the bank and putting it .

. .

Where

?

Ay, there's the

rub,

reflected January grimly. There were thieves aplenty in New

Orleans, and if you were keeping more than a few dollars cached in your attic

rafters, or under the floorboards of your bedroom, word of it soon got out. And

if you didn't happen to be rich enough that there were servants around your

house at all times, that money was eventually going to turn up gone.

He wasn't the

only man standing in Rue Royale looking at the closed-up doors of the Bank of

Louisiana that spring afternoon. As he turned away, Crowdie Passebon caught his

eye - the well-respected perfumer and the center of the libre community in the

old French Town. Like most of January's friends and neighbors, Passebon was the

descendant of those French and Spanish whites who'd had the decency to free the

children their slave women had borne them. January knew Crowdie had a great

deal more money than he did in the Bank, but nevertheless the perfumer crossed

to him and asked, Are you all right, Ben?'

'I'll

be

all right.'

Many people January knew - including most of his fellow musicians - didn't even

have the slim resources of a house.

Petronius

Braeden - a German dentist with offices on Rue St Louis - was haranguing a knot

of other white men outside the bank doors, cursing the new President:

hell, the man has only been in office a week, and see what

he done to the country already? We need Old Hickory back . . .

As

if it wasn't 'Old Hickory' who'd precipitated the whole mess and left it for

his successor to clean up.

January

walked on, shaking his head and wondering what the hell he and his beautiful

Rose were going to do.

It

had been a bad winter. Tightening credit and the plunge in the value of banks'

paper money meant that fewer white French Creoles - and far fewer Americans -

had given large entertainments, even at Christmas and Twelfth Night. January,

whose skill on the piano usually guaranteed him work every night of the week

from first frost 'til Easter, had found himself many nights at home. The same

spiral of rising prices and fewer loans had prompted many of the well-off white

gentlemen who had sent their daughters 'from the shady side of the street' to

board and be educated at the school that Rose operated in the big Spanish

house, to write Rose letters deeply regretting that Germaine or Sabine or Alice

would not be returning to the school this winter, and

we wish you all the best of luck . . .

And

we're surely going to need it

.

Other

well-off families - both white and

gens de couleur

libre -

had

decided that Mama or Aunt Unmarriageable would be perfectly able to take over

teaching the children the mysteries of the piano, rather than hiring Benjamin

January to do so at fifty cents a lesson. The last of them had broken this news

to January the previous week.

Since

early summer, January had been hiding part of what earnings he did make here

and there about the house - in the rafters, under the floorboards . . . But

summer was the starving- time for musicians, the time when you lived off the

proceeds of last year's Mardi Gras. The little money he'd made from lessons,

January had fallen into the habit of spending on groceries, so as not to touch

the slender reserve in the bank.

In

the God-damned locked-doors Lucifer-strike-you-all- with-lightning Bank of

Louisiana, thank you very much

.

Rose

was sitting on the front gallery when he climbed the steps. She'd been quiet

since the first time he'd walked to the bank that morning, for the week's

grocery money. Sunday would be Palm Sunday, and once Easter was done, the

planters who came into town for the winter, and the wealthier American

businessmen, would begin leaving New Orleans. Subscription balls ordinarily

continued up until April or May, but John Davis, who owned the Orleans

Ballroom, had told January that this year he was closing down early. With the

Bank of Louisiana out of business, January guessed that the American Opera

House - where he was supposed to play next week - would follow suit.

Rose

met his eyes, reading in them what he'd found - yet again that day - on Rue

Royale.

In

her quiet, well-bred voice, she said, 'Well, damn,' put her spectacles back on

and held up the letter that had been lying in her lap. 'Would you like the good

news first, or the bad news?'

'I'd

like this first.' January took the letter from her hand, dropped it to the

rough-made little table at her side, stood her on her feet and kissed her:

slender, gawky, with a sprinkle of freckles over the bridge of her nose and the

gray-hazel eyes so often found among the free colored. Though she stood as tall

as many men, against his six-foot-three bulk she felt delicate, like a sapling

birch. 'You're here sitting on the gallery of our house. No bad news can erase

that; no good news can better it.'

She

sighed and put her head briefly against his shoulder. He felt her bones relax

into his arms.