The Silent Duchess

THE SILENT DUCHESS

by Dacia Maraini

Translated from the Italian by Dick Kitto and

Elspeth Spottiswood

Afterword by Anna Camaiti Hostert

Published by:

The Feminist Press at The City University of New York

Wingate Hall/city College Convent Avenue at 138th Street

New York, NY 10031.

Copyright 1990 by RCS Rizzoli Libri S.p.a.

English translation copyright 1992 by Dick Kitto and

Elspeth Spottiswood Afterword copyright 1998 by

Anna Camaiti Hostert

BOOK JACKET INFORMATION

THE INTERNATIONAL BESTSELLER WINNER OF THE

PREMIO CAMPIELLO

"Maraini brilliantly conveys the mixture of luxury and squalor in which the Sicilian aristocracy lived. ... The Silent Duchess manages totally to overpower the reader with its narrative urgency. ... Since she won the Prix Formentor in 1963, Dacia Maraini has produced nothing finer than this."

--Evening Standard, London

"The Silent Duchess has a subtlety of perception, a delicacy in probing emotions and above all, an elusive feel for history itself. ... The narrative has the richness of a saga. ... This history of a woman's quest for dignity is an astonishing achievement."

--The Independent, London

"This is a novel of the greatest vividness. It arouses intense feeling. It provokes thought. It invites the reader into a world which is very different from that in which we live, and yet immediately recognizable as true and valid. ... It is illuminating, moving, and entrancing."

--The Scotsman, Edinburgh

"Dacia Maraini has produced a fiction of elegance and charm."

--The Mail on Sunday, London

"A thoughtful and beautifully written book." --Sunday Express, London

Winner of the Premio Campiello (italy's equivalent of the National Book Award), short-listed for the Independent Foreign Fiction Award upon its first English-language publication in the U.k., and published to critical acclaim in fourteen languages, this mesmerizing historical novel by Italy's premier woman writer is available in the United States for the first time.

Set in Sicily in the early eighteenth century, THE SILENT DUCHESS is the story of Marianna Ucr@ia, the daughter of an

aristocratic family and the victim of a mysterious childhood trauma that has left her deaf and mute, trapped in a world of silence. Set apart from the world by her disability, Marianna searches for knowledge and fulfillment in a society where women face either forced marriages and endless childbearing or a life of renunciation within the walls of a convent.

When she is just thirteen years old, Marianna is forced to marry her own aging uncle. Her status and wealth as a duchess cannot protect her from many of the horrors of that time: she witnesses her mother's decline due to her addiction to opium and snuff and her father's cruelly misguided religious piety as he participates in the hanging of a young boy. She watches helplessly as her four-year-old son dies of smallpox and her youngest daughter is married off at the age of twelve. It is not until the death of her "uncle-husband" that Marianna at last gains freedom from her life of subservience: she learns to manage her estates and to love a man as she had never loved her husband, and she also learns of the unspeakable events that led to her lifelong silence.

In luminous language that conveys both the keen visual sight and deep human insight posessed by her remarkable main character, Dacia Maraini captures the splendor and the corruption of Marianna's world and the strength of her spirit. THE SILENT DUCHESS is the timeless story of one woman's struggle to find her own voice after years of silence.

DACIA MARAINI is the author of more than fifty books, including novels, plays, collections of poetry, and critical essays. Her second novel, The Age of

Discontent, won the international Prix Formentor, and The Silent Duchess received one of Italy's highest literary honors, the Premio Campiello. Among her other novels available in English are Women at War and the recent Voices. Several of Maraini's works have been adapted for the stage or screen, and she herself has directed both plays and films. Early in her career, Maraini founded the literary review Tempo di

Letteratura; she later established an all-women's theater group, Teatro della

Maddalena, and became known as a theorist and activist in the Italian feminist movement of the 1970's. Born in Florence, Dacia Maraini currently resides in Rome.

ANNA CAMAITI HOSTERT received a Ph.d. in philosophy from the University of Pisa and a second in Italian language and literature from the University of Chicago. She currently teaches at the University of Illinois, Chicago, and is author of books and articles on feminism, politics, and film.

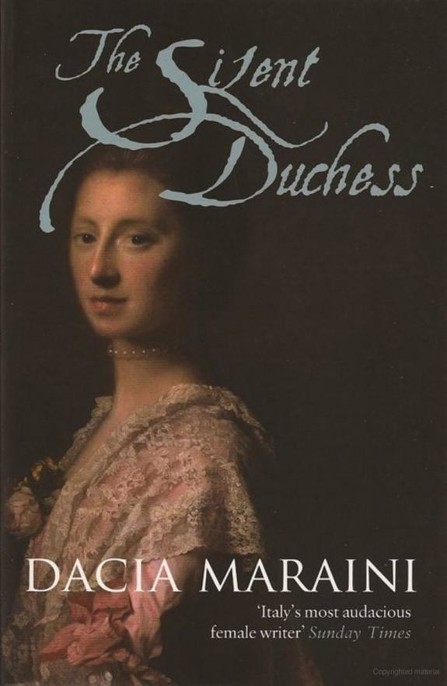

Jacket design: Claire Ultimo, Ultimo Incorporated

Front jacket art: Angelica Kauffman (swiss, 1741-1807).

A Bust of a Girl with an Earring, 1770. Etching, 5 by 3-3/4 in. (12.7 by 9.5 cm.) The National Museum of Women in the Arts. Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay.

Originally published in 1990 in Italian as La lunga vita di Marianna Ucr@ia by RCS Rizzoli Libri S.p.a., Via Mercenate 91, 20138 Milan, Italy. Published by arrangement with RCS Rizzoli Libri. English translation originally published in 1992 in Great Britain by Peter Owen Publishers, 73 Kenway Road, London SW5 0OR, England. Published by arrangement with Peter Owen Publishers.

The Feminist Press would like to thank Helene D. Goldfarb, Florence Howe, Joanne Markell, Caroline Urvater, Genevieve Vaughan, Patricia Wentworth and Mark Sagan, and Marilyn Williamson for their generosity in supporting this publication.

Special thanks to Rose Trillo Clough and Sara Clough for encouraging The Feminist Press to give voice to The Silent Duchess.

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTES

In the print edition single quotes were used for outer quotation marks and double quotes for inner quotation marks, except in the Afterword. In this braille edition, dots 2-3-6 and 3-5-6 are used for outer quotes and dots 6, 2-3-6 and 3-5-6, 3 for inner quotes.

THE SILENT DUCHESS

The Ucr@ias

a family tree

(great-grandfather) Signoretto Ucr@ia of Fontanasalsa

Aunt Manina (unmarried)

Aunt Agata (canoness) (grandfather) Mariano more. (grandmother) Giuseppa

Gerbi of Mansueto

Aunt Teresa (prioress)

Duke Signoretto Ucr@ia of Fontanasalsa more. Maria

Signoretto more. Domitilla Olivo

Carlo (abbot)

MARIANNA more. her uncle, Duke Pietro

Felice (nun)

Giuseppa more. Giulio Carbonelli

Manina more. Francesco Chiarad@a Mariano more. Caterina Mol`e di

Flores

Signoretto

Fiammetta (canoness) Geraldo

Agata more. Prince Diego of Torre Mosca

Eduardo Gerbi of Mansueto (grandmother) Giuseppa Gerbi of Mansueto

more. (grandfather) Mariano Carlo Ucr@ia of Campo Spagnolo more.

Giulia Scebarr@as

Maria more. Duke Signoretto Ucr@ia of Fontanasalsa

Duke Pietro Ucr@ia of Campo Spagnolo more. his niece MARIANNA

I

Here they are, a father and a daughter. The father fair, handsome, smiling; the daughter awkward, freckled, fearful. He stylish and casual, his stockings ruffled, his wig askew; she imprisoned inside a crimson bodice that highlights the wax-like pallor of her complexion.

The little girl watches her father in the mirror as he bends down to adjust his white stockings over his

calves. His mouth moves but the sound of his words is lost as it reaches her ears, as if the visible distance between them were only a stumbling block: they seem to be close but they are a thousand miles apart.

The child watches her father's lips as they move more and more rapidly. Although she cannot hear him, she knows what he is saying: that she must hasten to bid goodbye to her lady mother, that she must come down into the courtyard with him, that he is in a hurry to get into his carriage because as usual they are late.

Meanwhile Raffaele Cuffa, who when he is in the hunting lodge walks with silent watchful footsteps like a fox, approaches Duke Signoretto and hands him a large wicker basket on which a white cross stands out prominently. The Duke opens the lid with a flick of his wrist, which his daughter recognises as one of his most habitual gestures, a peevish movement with which he casts to one side anything that bores him. His indolent, sensual hand plunges into the well-ironed cloth inside the basket, shivers at the icy touch of a silver crucifix, squeezes the small bag full of coins, and then slips quickly away. At a sign from him, Raffaele Cuffa hastens forward to close the basket. Now it is only a question of getting the horses to gallop full speed to Palermo.

Meanwhile Marianna has rushed to her parents' bedroom, where she finds her mother the Duchess lying supine between the sheets, her dress fluffed up with lace slipping off her shoulder, the fingers of her hand closed round the enamel snuff-box. The child stops for a moment, overcome by the honey-sweet scent of the snuff mingled with all the other odours that accompany her mother's awakening: attar of roses, coagulated sweat, stale urine and lozenges flavoured with orris root.

Her mother presses her daughter to her with lazy tenderness. Marianna sees her lips moving, but she can't be bothered to guess at her words. She knows she is telling her not to cross the road on her own; because of her deafness she could easily be crushed under the wheels of a carriage she has not been able to hear. And then dogs: no matter whether they are large dogs or small dogs she must give them a wide berth. She knows perfectly well how their tails grow so long that they wrap themselves round people's waists like chimeras do and then, hey presto, they pierce you with their forked points and

then you are dead without ever realising what has happened to you.

For a moment the child fixes her gaze on her mother the Duchess's plump chin, on her beautiful mouth with its pure outline, on her soft pink cheeks, on her eyes with their look of innocence, yielding and far away. I shall never be like her, she says to herself. Never. Not even when I am dead.

Her mother the Duchess continues to talk about dogs like chimeras that can become as long as serpents, that press against you with their whiskers, that bewitch you with their cunning eyes. But the child gives her a hasty kiss and runs off.

Her father the Duke is already in the carriage, but instead of summoning her he is singing. She can see him puffing out his cheeks and arching his eyebrows. As soon as she puts a foot on the running-board she is seized from inside and pulled on to the seat. The carriage door is closed with a sharp bang. Peppino Cannarota whips the horses and off they go at a gallop.

The child relaxes, sinks back into the padded seat and shuts her eyes. Sometimes the two senses on which she relies are so alert that they come to blows, her eyes intent on possessing every image in its entirety, and her sense of smell obstinately insisting that it can make the whole world pass through these two minute tunnels of flesh at the lower end of her nose.

But now she has lowered her eyelids so as to rest her eyes for a while, and her nostrils have begun to draw in the air, recognising the smells and meticulously noting them in her mind: the overpowering scent of lettuce water that impregnates her father's waistcoat, below that the scent of rice powder mingled with the grease on the seats, the sourness of crushed lice, the smarting from the dust on the road that blows through the joints of the doors, as well as the faint aroma of mint that floats in from the fields of the Villa Palagonia.

But an extra hard jolt makes her open her eyes. Opposite her on the front seat her father is asleep, his tricorn hat capsized over his shoulder, his wig askew on his handsome perspiring forehead, his blond eyelashes resting gracefully on his carelessly shaven cheeks. Marianna pushes aside the small wine-coloured curtain, embroidered with golden eagles. She catches a glimpse of the dusty

road and of geese streaking away with outspread wings in front of the carriage wheels. Images of the countryside round Bagheria glide into the silence within her head: the contorted cork trees with their naked reddish trunks, the olive trees with branches weighed down by their little green eggs, the brambles that are struggling to invade the road, the cultivated fields, the giant cactuses with their spiny fruit, the tufts of reed, and far away in the distance the windswept hills of Aspra.

Now the carriage passes the two pillars of the gate to the Villa Butera and sets off towards Ogliastro and Villabate. Her small hand remains gripping the cloth, heedless of the heat that seeps through the coarse woollen weave. She sits straight upright and motionless to avoid accidentally making a noise that will wake her father. But how stupid! What about the noise of the wheels as they clatter over the potholes in the road; what about Peppino Cannarota shouting encouragement to the horses; and the cracking of the whip and the barking of dogs? Even if she can only imagine all these sounds, for him they are real. And yet it is she who is disturbed and not him. What tricks intelligence can play on crippled senses!

From the gentle shimmering of the reeds, hardly affected by the wind from Africa, Marianna is aware that they have arrived at the outskirts of Ficarazzi. In the distance is the big yellow barracks known as "the sugar mill". A pungent acidulous smell creeps through the cracks in the closed door. It is the smell of sugar cane as it is cut, soaked, stripped and transformed into molasses.

Today the horses are flying along. Her father the Duke continues sleeping in spite of the jolts. She is pleased to have him there safe in her hands. Every so often she leans forward to straighten his hat or to brush away a too insistent fly.

The child is just seven years old. In her disabled body the silence is like dead water. In this clear still water float the carriage, the balconies hung with washing, the hens scratching about, the sea glimpsed from afar, her sleeping father. The images are almost weightless and easily change their positions, but they coalesce into a liquid that blends their colours and dissolves their shapes.