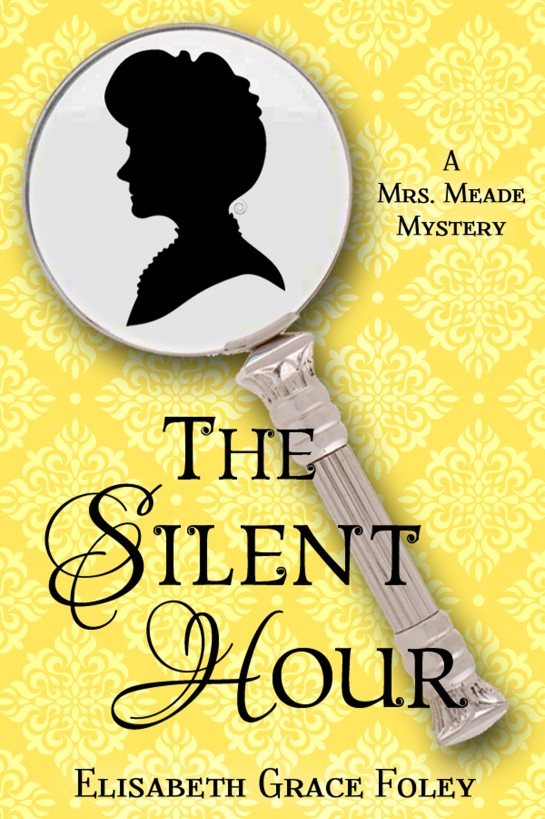

The Silent Hour

Authors: Elisabeth Grace Foley

Tags: #historical fiction, #woman sleuth, #colorado, #cozy mystery, #novella, #historical mystery, #short mystery, #lady detective

The Silent Hour: A Mrs. Meade Mystery

By Elisabeth Grace Foley

Cover design by

Historical

Editorial

Silhouette artwork by Casey Koester

Formatting by

Second Sentence Press

Photo credits

Wallpaper © Evdakovka | Vectorstock.com

Magnifying glass © mvp | Fotolia.com

This e-book is licensed for your personal enjoyment

only. This e-book may not be re-sold or given away to other people.

If you would like to share this book with another person, please

purchase an additional copy for each person. If you’re reading this

book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use

only, then please return to your favorite ebook retailer and

purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of

this author.

Copyright © 2015 Elisabeth Grace Foley

Table of Contents

Kill men i' the dark!—Where be these bloody

thieves?—

How silent is this town!—Ho! murder! murder!

- William Shakespeare

Frances finished cleaning the blackboard and

piled together the few books on her desk. She swept the floor in

front of the blackboard and around the stove, then stood by the

door and took a last look around the schoolhouse, now empty and

clean, before donning her jacket and hat, gathering up her books

and departing.

The Sour Springs schoolhouse stood at the end

of a little side canyon two miles south of town, whose steep walls

were clothed in rich green pine with a cloud of golden-orange

aspens below. The aspen leaves were trembling on their stalks in

the autumn breeze as Frances Ruskin stepped from the door of the

schoolhouse, but they had not yet begun to fall. In fair weather

Frances liked the walk of a mile or so down the road to the house

where she boarded; only in the winter did it take a horse to plough

up through the drifts of snow in the canyon. Today, however, she

turned the opposite way, bound for a certain spot by the side of

the road which she had come to know as a meeting-place.

Frances walked slowly, letting her arms swing

free; her books in one hand and her head tilted back to breathe in

the crisp, brilliant Colorado air. The ochre and dark-green of the

trees, the vaulted walls of the canyon, made her heart swell with

almost painfully keen appreciation of their beauty. Never before

had autumn touched her so to the quick. There was a sameness about

summer after all…its blues and greens unchanging, except near the

end when the shades grew a little tarnished…autumn was a season of

change, of finding new colors and unexpected new beauties every day

in places that had seemed drab before. To Frances it seemed a

metaphor of her own life—everything that had happened to her before

this autumn felt vague, unimportant, all of it the same. She dated

her existence from the day, exactly three weeks and two days ago,

when love came into her life.

Frances was twenty-three, and had been

teaching school in Sour Springs for two years. She was not

beautiful, but she had clear, pleasant features, frank gray eyes

and soft brown hair. She had been accustomed to working from an

early age; to providing for others in her family; and later when

left alone, to providing for herself. Reserved by nature, and with

scarcely any opinion of her own talents and attractions, it had

taken her a while to be slowly drawn into the social life of Sour

Springs by a few livelier girls who befriended her. It was at their

urging she had gone rather reluctantly to an early-autumn picnic of

young people just over a year ago, not expecting very much. But she

had

enjoyed herself, far more than she had anticipated, and

it was there that she had met Jim Cambert. Jim was nearly four

years younger than her; intelligent, a good conversationalist, and

talked to her freely without seeming to notice her slight hesitant

reserve that soon melted away in his company. A friendship sprang

up between them from then on—they got on well and never seemed

short of things to talk about; and in the months that followed,

their easy companionship became one of the bright spots in Frances’

life, seeming to broaden the horizons of her quiet, unremarkable

existence.

It had come as a shock to both of them to

discover, almost simultaneously, that their feelings for each other

had gone deeper, for the very reason that the thought had never

entered their minds since the beginning. But after the first

moments or hours of standing open-mouthed before the revelation,

nothing could have seemed more natural. The close bond between them

had already been formed before they were aware of it.

Frances came to a quiet bend in the canyon

road, and sat down on the shallow bank beside it. She sat there a

little while, watching the first few gold leaves fall gently, until

she heard the clip of approaching hooves, and Jim Cambert came

around the bend on his tall black horse. He pulled up and

dismounted at the side of the road and came over, looking down at

her with eyes warm with happiness, and then he sat down beside her

on the bank and kissed her. Frances’ fingers tightened on his coat

sleeve and she closed her eyes, enjoying the little thrill, the

more precious to her because it was something she had never thought

she would have. She lingered close to him for a long moment.

After a little while Jim drew back and smiled

at her again. He was tall and athletic and golden-haired, with a

confident air about him, and it was only when you looked him

closely in the eye that you realized with some surprise how young

he was. His matter-of-fact maturity was the product of an unusual

and colorful upbringing—orphaned as a child and taken in by his

grandfather, an old career soldier, he had grown up in barracks and

outposts and garrison towns across the country, most of his time

spent among adults. His education had been unorthodox but

broad—Major Cambert was a prolific reader who carried a ponderous

library with him from post to post, swelled by volumes he forgot to

return to their owners and thinned again by those he scattered

among friends along the way. Eventually the Major retired and

bought a small cattle ranch near Sour Springs, and when rheumatism

began to bind him to his easy-chair, Jim at sixteen became his eyes

and ears and feet on the ranch, and by now practically ran it

himself, subject only to Major Cambert’s instructions and

approval.

They sat for a while on the sunny bank, hands

clasped simply in each other’s, and talked of their future. They

had been too happy to think and speak in terms of earth much

before.

“I don’t see why we can’t get married next

week,” said Jim only half jokingly. “A month isn’t too short an

engagement when we’ve known each other this long. It isn’t as if we

have anything to do beforehand.”

“I’d love to,” said Frances, smiling, “but I

do feel I should go on teaching to the end of this term. If I stay

on to the Christmas holidays it’ll give the school board time to

find another teacher.”

“Christmas,” said Jim with a rueful grin.

“Well, I suppose you’re right. Have you told the board you’ll be

leaving yet?”

“No, not yet. We hadn’t made any plans,

so—I’ll give them my resignation tomorrow.” Frances hesitated just

a second, and then said, “Have you—have you told your

grandfather?”

“No, I haven’t. I guess I’ve hardly been able

to believe it myself, enough to tell it to anyone else.”

“You should,” said Frances. “It wouldn’t be

right to leave him not knowing till the last minute—and anyway, he

really ought to be the first to know.”

Jim laughed. “All right. I’ll tell

Grandfather tonight, and you can tell the board tomorrow.”

“What do you think he’ll say?” said

Frances.

“Grandfather? He’ll be tickled to death.

He’ll like having a woman in the house—it’ll make us a family

instead of a barracks. And don’t think you’ll be burdened with

taking care of him, Frances. Grandfather can’t get out of the house

much, but he’s not a complete invalid; he can hobble around indoors

with a little help from me.”

“I’m glad,” said Frances. “Glad that he’ll be

pleased, I mean. And I wouldn’t mind taking care of him if I did

need to. I—” She drew a soft little breath. “It’s all so wonderful

I can hardly credit it either. I never really dreamed much about

anything…I guess I always supposed I would go on teaching school

forever, and nothing much would ever happen to me. And now…I’m so

happy, Jim.”

Jim lifted both her hands, twining his

fingers between hers, and looked down into her eyes. “I love you,

Frances,” he said softly.

She looked up at him, her heart too full for

speech. Jim drew her into his arms and kissed her again, and the

autumn breeze slipped in a cool invisible swirl around them,

whisking a golden leaf past on a beam of sunlight.

* * *

The fire burning steadily in the fireplace

was a good one, but it looked almost small sitting back from the

center of the broad stone hearth. The big fireplace with Major

Cambert’s armchair beside it dominated the not overly large room,

which also held a battered desk filled with papers, a small iron

safe and a couple of comfortably overflowing bookcases. The room

was dark except for the fire-glow, as was the Major’s custom in the

evenings; the shifting gold light half illuminated the

weather-lined face and gray moustache of the old soldier sitting

back in his chair, an old red rug over his knees. Across from him

Jim was sitting bent forward with his elbows on his knees, kneading

his hands together, and every now and then glancing into the fire

with a little half-hidden smile as he tried to think how you put

together the words to explain about something so special.

“Grandfather, I’ve got something to tell

you,” he said at last.

“Eh? What is it?” said Major Cambert around

the stem of his pipe, as he adjusted it in his mouth.

His complacency was too much for the

happiness bubbling up inside Jim, who was obliged to get up and

stir the fire before he could go on. He did a thorough job of it,

returned the poker to its rack, and then turned around and stood on

the hearth facing his grandfather, his thumbs hooked in his belt.

“I’ve decided I want to get married.”

Major Cambert’s jaw dropped, and he stared at

his grandson for a moment, and then slowly he began to shake with

soundless laughter, which gave way to audible mirth. “You do, do

you! And when did you reach that decision?”

“Well, it happened pretty suddenly,” said Jim

with a shy smile.

“And now you’ve only to look about for the

girl, I suppose,” said Major Cambert, trying to be grave.

“Oh, no, I’ve already found one. As a matter

of fact,” said Jim, “well—I’m engaged.”

Major Cambert took his pipe out of his mouth

altogether and looked at his grandson with something like a new

respect. “Well…! Who is she, then?”

Jim plunged enthusiastically into speech.

“Frances Ruskin. You know her, of course. I met her a year ago.

You’ve met her once or twice when we were in town; I’m sure you

remember her.”

A frown slowly overtook Major Cambert’s

smile; the indulgent light faded from his eyes. “Miss—Ruskin—the

schoolteacher?”

“Yes! You remember talking to her, at the

Literary Society meeting back in the spring. She—”

“The schoolteacher?” said Major Cambert

again. He gave his grandson a look that was certainly not one of

approval, and then uttered a short dismissive sound, almost of

contempt. “Why, she’s no girl! She must be twenty-six if she’s a

day.”

“She’s only twenty-three,” said Jim, a little

stiffly, “and I don’t see what difference that makes.”

“Difference!” said Major Cambert. “It makes a

sight more difference than you’ve thought about, my boy. Why do you

want to marry her?”

Jim said, with ominous articulation, “Because

I love her, and she loves me. That’s what’s customary, isn’t

it?”

The Major gave a short bark of a laugh. “Tell

my old grandmother! Yes, I’ve seen the girl. She’s twenty-three,

going on twenty-four more than likely, and you’re not twenty yet.

Why would she want you when she could have a grown man? If she’s

accepted you, it’s because she can’t

get

a man, I’ll wager.

She knows what side her bread’s buttered on.”

“A

man

?” said Jim, his voice

strangled. “I’ve been your right hand for the past four years—I’ve

heard you say it to people time and again—and now you sit there and

tell me I’m not a man?”

“Not when it comes to women you’re not,” said

Major Cambert, scowling darkly, and moving from side to side in his

chair as he always did when upset. “You don’t know the first thing,

boy. You ought to take up with some flowery little chit of sixteen

who doesn’t know any more than you do.”