The Silk Road: A New History (20 page)

Read The Silk Road: A New History Online

Authors: Valerie Hansen

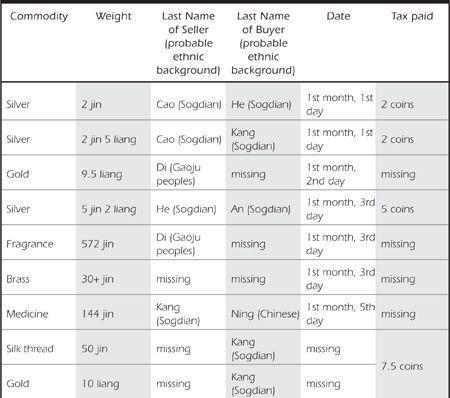

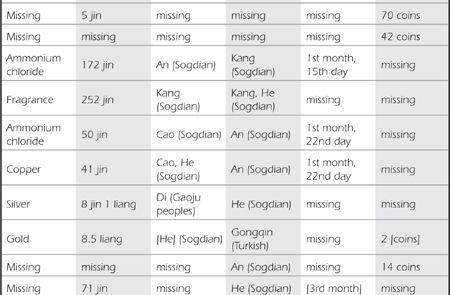

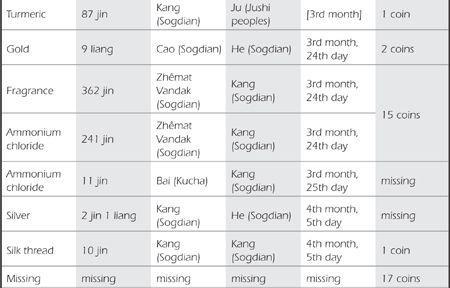

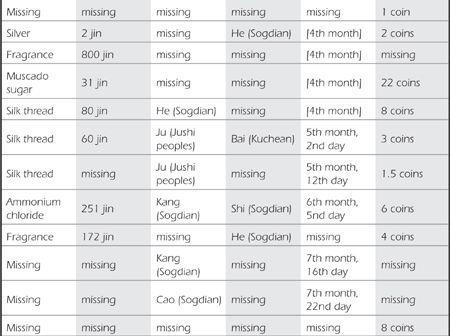

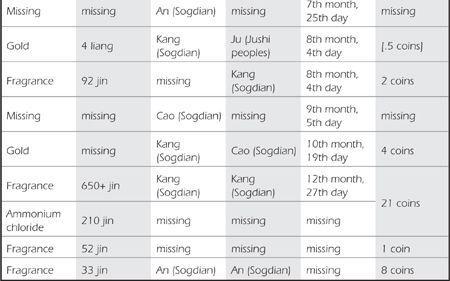

Even so, these records highlight the dominant role played by Sogdians in the Silk Road trade. Of the forty-eight names mentioned either as purchasers or sellers of a given good, fully forty-one are Sogdian.

63

The scale-fee records suggest a relatively low frequency of trade—a handful of transactions each week—with many weeks in which no tax was collected.

64

Officials recorded all the sales by each day and then twice a month tallied up the total number of coins they collected. The rate of taxation was two silver coins (weighing 8 grams) on two Chinese pounds (

jin

) of silver, less than one percent. Scholars do not know how much a jin weighed in the year 600: either 6 ounces (200 grams) in the older system or about 1 pound, 3 ounces (600 grams) in the newer one. The lower weight is more likely, but the accompanying chart uses the original units of jin and

liang

(a Chinese ounce, with sixteen to a jin) because of the uncertainty.

65

The scale-fee register lists thirty-seven transactions over the course of a single year. Brass, medicine, copper, turmeric, and raw sugar traded hands only once, while other goods appear more often: gold, silver, silk thread, aromatics (the term

xiang

refers broadly to spice, incense, or medicine), and ammonium chloride. The one unfamiliar item on the list, the chemical ammonium chloride, was used as an ingredient in dyes, to work leather, and as a flux to lower the temperature of metals. These documents list ammonium chloride six times, in amounts from a low of 11 Chinese pounds to a high of 251 Chinese pounds. Fragrance, similarly, was traded in both small and large amounts, with a low of 33 Chinese pounds and a high of 800 Chinese pounds—the largest single amount recorded on the list. Gold, as one would expect, appears in small amounts ranging from a quarter to more than half a Chinese pound, and the largest amount of silver did not exceed 8 Chinese pounds. Surprisingly, these documents do not mention bolts of silk cloth, but, since their value was determined by width and length, they would not have been subject to a tax by weight.

66

TABLE 3.1 SCALE-FEE TAX RECEIPTS FOR ONE YEAR AT ONE CHECKPOINT NEAR TURFAN, CA. 600 CE

The scale-tax documents do not list all the inventory of a given merchant, just individual sales, but even the largest quantity mentioned—800 Chinese pounds—could have been carried by several pack animals.

67

We glimpse the same low level of trade in a series of affidavits given during the legal dispute mentioned in the introduction between a Chinese merchant and the brother of his business partner.

68

The plaintiff’s Chinese name was Cao Lushan, a clear indicator that he was Sogdian; Cao was one of the nine jeweled surnames, and Lushan was the transcription of Rokhshan, a Sogdian name meaning “bright,” “light,” or “luminous,” cognate with our Persian-derived name Roxanne.

Appearing before a Chinese court sometime around 670, the younger brother sued a Chinese merchant for the return of an unpaid loan. The Chinese merchant had violated Tang-dynasty contract law, in effect since the 640 conquest of Turfan, the Sogdian contended. As his brother’s heir, he was entitled to 275 bolts of silk. He brought the suit in Turfan, which served as the headquarters of the Anxi Protectorate between 670 and 692.

At the time of the brother’s death, both he and his Chinese partner, like many merchants of the time, maintained households in the Tang capital of Chang’an and traveled the long route to the Western Regions when business required it. The brother had met his Chinese partner in Gongyuecheng (modern-day Alma-ligh, Xinjiang, near the Chinese border with Kazakhstan) and lent him 275 bolts of silk, which could be carried on several pack animals. Since the two men did not have a common language, they spoke through an interpreter.

As this case demonstrates, plain silk—undyed with a simple basket-weave pattern—served as a currency alongside bronze coins during the Tang dynasty. Silk had many advantages over bronze coins. The value of the coins fluctuated wildly while the price of silk was more stable. The dimensions of a bolt of silk held remarkably steady between the third and the tenth centuries at 1 Chinese foot, 8 inches (22 inches, or 56 cm) wide and 40 Chinese feet (39 feet, or 12 m) long.

69

Also, silk was lighter than bronze coins; the standard unit of one thousand coins could weigh as much as nine pounds (4 kg).

70

After making the loan the Sogdian went south to Kucha, leading two camels, four cattle, and one donkey. These seven pack animals carried his goods, which included silk, bows and arrows, bowls, and saddles. The Sogdian never made it to Kucha; one witness in the trial speculated that he had been killed by bandits who stole his goods. Even though the surviving brother did not have a copy of the original loan agreement, he was able to present two witnesses, both Sogdians, to the signing of the contract. According to Tang law, their oral testimony constituted sufficient proof of the original agreement. The Chinese court ruled in favor of the living Sogdian brother and against the Chinese merchant, ordering him to repay his debt.

The deceased Sogdian brother had traveled with seven pack animals carrying his goods. Other caravans were about the same size, as we learn from twelve surviving travel passes found at Turfan. Like similar documents from Niya and Kucha, these record the members of each party—both people and animals—proceeding together from one destination to another and all the places to which they were allowed to go. At the beginning of his trip, each traveler applied for a travel pass that listed his ultimate destination, a few intermediate points, and the people and animals traveling with him. In addition, each time he entered a new prefecture, he received a document verifying the people and animals traveling with him.

At every guard station, both within and between prefectures, local officials checked that all the people—classified as relatives of the primary traveler, servants (

zuoren

), or slaves—and all the draft animals rightfully belonged to him. Tang-dynasty law prohibited the enslavement of people to repay debts; the only legal slaves were those who were born to slave parents or who had been purchased with a contract registered with the authorities and who had the proper market certificate to show for it.

71

Tang law was equally strict about animals: a traveler could bring a donkey, horse, camel, or cow by a checkpoint only if he carried a market certificate for any purchased animals. Like officials at Kucha, Turfan officials did not record what cargo each caravan carried. Still, the travel passes do give the size of caravans, which usually included four or five people and about ten animals.

72

One merchant, named Shi Randian (in Sogdian, Zhemat-yan, “Favor of the god Zhemat”), appears in several documents, so it is possible to track his movements in the years 732 and 733 and to grasp the level of government supervision. With his household registered in Turfan, Shi carried a travel pass allowing him to proceed from Guazhou to Hami via Dunhuang and then all the way west to Kucha, on a route similar to Xuanzang’s. Surviving documents record the approval of four different officials on the leg from Guazhou to Dunhuang. The caravan was checked two times on the nineteenth day of the third month, once on the twentieth day, and again on the twenty-first day.

73

On his first trip, Shi traveled with two servants, a slave, and ten horses, but on his way back he had purchased an additional horse (for eighteen rolls of silk) and a mule.

74

Since he carried the necessary market certificate demonstrating he had purchased them legally, he was allowed to proceed. A small-scale trader, Shi carried his wares on ten horses, and bought and sold individual animals from time to time to augment his income.

Officials did stop those caravans whose papers were not in order. In 733, one resident of Chang’an, Wang Fengxian, was returning from a trip supplying the army in Kucha. He applied for a new travel pass, because he had diverged from his permitted route to pursue a debtor who, he said, owed him three thousand bronze coins. Local officials apprehended him in a town to which he had not been given permission to travel. When he explained that he had fallen ill, and others verified his account, they allowed him to proceed.

75

The Turfan travel passes, like those from Niya and Kucha, confirm that all travelers were subject to the intense scrutiny of the authorities and could not diverge from their itineraries without official permission.