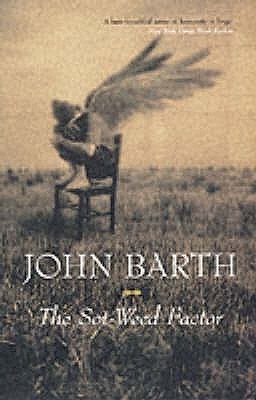

The Sot-Weed Factor

Read The Sot-Weed Factor Online

Authors: John Barth

The Sot-Weed Factor

(Second Edition)

by John Barth

a.b.e-book v3.0 / Scan Notes at EOF

Back Cover

The great American novel of anti-Americana

"Outrageously funny, villainously slanderous. . . The book is a bare-knuckled satire of humanity at large. . . Barth's masterstroke is an alleged secret journal of Capt. John Smith. Its version of the Pocahontas story is truly Rabelaisian and marvelously executed." --

The New York Times Book Review

"

The Sot-Weed Factor

is that rare literary creation -- a genuinely serious comedy. . . Ebenezer Cooke, in this boisterous historical farce, emerges as one of of the most diverting heroes to roam the world since Candide." --

Time

All of the characters in this book are fictitious,

and any resemblance to actual persons, living

or dead, is purely coincidental.

This low-priced Bantam Book

has been completely reset in a type face

designed for easy reading, and was printed

from new plates. It contains the complete

text of the original hard-cover edition.

NOT ONE WORD HAS BEEN OMITTED.

THE SOT-WEED FACTOR

A Bantam Book

/

published by arrangement with

Doubleday & Company, Inc.

PRINTING HISTORY

Doubleday edition published 1960

Doubleday revised edition published 1967

Bantam edition

/

May 1969

2ndprinting

......

April 1970 5th printing

.......

July 1973

3rd printing

......

April 1971 6th printing

.....

August 1974

4th printing

......

April 1972 7th printing

......

June 1975

All rights reserved.

Copyright © 1960, 1967 by John Barth.

This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by

mimeograph or any other means, without permission.

For information address: Doubleday & Company, Inc.,

243 Park Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10017.

ISBN 0-553-10471-3

Published simultaneously in the United States and Canada

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Foreword to the Second Edition

I

've taken the opportunity

to reread

The Sot-Weed Factor

with an eye to emending and revising the text of the original edition before its reissue, quite as Ebenezer Cooke himself did in 1731 with the poem from which this novel takes its title. The cases differ in that Cooke's objective was to blunt the barbs of his original satire, he having dwelt by then many years among its targets, but mine is merely, where possible, to make this long narrative a quantum swifter and more graceful.

Buffalo, New York 1966

John Barth

Contents

Foreword to the Second Edition

1: The Poet Is Introduced, and Differentiated from His Fellows

2: The Remarkable Manner in Which Ebenezer Was Educated, and the No Less Remarkable Results of That Education

3: Ebenezer Is Rescued, and Hears a Diverting Tale Involving Isaac Newton and Other Notables

4: Ebenezer's First Sojourn in London, and the Issue of It

5: Ebenezer Commences His Second Sojourn in London, and Fares Unspectacularly

6: The Momentous Wager Between Ebenezer and Ben Oliver, and Its Uncommon Result

7: The Conversation Between Ebenezer and the Whore Joan Toast, Including the Tale of the Great Tom Leech

8: A Colloquy Between Men of Principle, and What Came of It

9: Ebenezer's Audience With Lord Baltimore, and His Ingenious Proposal to That Gentleman

10: A Brief Relation of the Maryland Palatinate, Its Origins and Struggles for Survival, as Told to Ebenezer by His Host

11: Ebenezer Returns to His Companions, Finds Them Fewer by One, Leaves Them Fewer by Another, and Reflects a Reflection

1: The Laureate Acquires a Notebook

2: The Laureate Departs from London

3: The Laureate Learns the True Identity of Colonel Peter Sayer

4: The Laureate Hears the Tale of Burlingame's Late Adventures

5: Burlingame's Tale Continued, Till Its Teller Falls Asleep

6: Burlingame's Tale Carried Yet Farther; the Laureate Reads from

The Privie Journall of Sir Henry Burlingame

and Discourses on the Nature of Innocence

7: Burlingame's Tale Concluded; the Travelers Arrive at Plymouth

8: The Laureate Indites a Quatrain and Fouls His Breeches

9: Further Sea-Poetry, Composed in the Stables of the King o' the Seas

10: The Laureate Suffers Literary Criticism and Boards the

Poseidon

11: Departure from Albion: the Laureate at Sea

12:, The Laureate Discourses on Games of Chance and Debates the Relative Gentility of Valets and Poets Laureate. Bertrand Sets Forth the Anatomy of Sophistication and Demonstrates His Thesis

13: The Laureate, Awash in a Sea of Difficulties, Resolves to Be Laureate, Not Before Inditing Final Sea-Couplets

14: The Laureate Is Exposed to Two Assassinations of Character, a Piracy, a Near-Deflowering, a Near-Mutiny, a Murder, and an Appalling Colloquy Between Captains of the Sea, All Within the Space of a Few Pages

15: The Rape of the

Cyprian;

Also, the Tale of Hicktopeake, King of Accomack, and the Greatest Peril the Laureate Has Fallen Into Thus Far

16: The Laureate and Bertrand, Left to Drown, Assume Their Niches in the Heavenly Pantheon

17: The Laureate Meets the Anacostin King and Learns the True Name of His Ocean Isle

18: The Laureate Pays His Fare to Cross a River

19: The Laureate Attends a Swine-Malden's Tale

20: The Laureate Attends the Swine-Malden Herself

21: The Laureate Yet Further Attends the Swine-Malden

22: No Ground Is Gained Towards the Laureate's Ultimate Objective, but Neither Is Any Lost

23: In His Efforts to Get to the Bottom of Things the Laureate Comes Within Sight of Malden, but So Far from Arriving There, Nearly Falls Into the Stars

24: The Travelers Hear About the Singular Martyrdom of Father Joseph FitzMaurice, S.J.: a Tale Less Relevant in Appearance Than It Will Prove in Fact

25: Further Passages from Captain John Smith's

Secret Historic of the Voiage Up the Bay of Chesapeake:

Dorchester Discovered, and How the Captain First Set Foot Upon It

26: The Journey to Cambridge, and the Laureate's Conversation by the Way

27: The Laureate Asserts That Justice Is Blind, and Armed With This Principle, Settles a Litigation

28: If the Laureate Is Adam, Then Burlingame Is the Serpent

29: The Unhappy End of Mynheer Wilhelm Tick, As Related to the Laureate by Mary Mungummory, the Traveling Whore o' Dorset

30: Having Agreed That Naught Is in Men Save Perfidy, Though Not Necessarily That

Jus est id quod aliens fecit,

the Laureate at Last Lays Eyes on His Estate

31: The Laureate Attains Husbandhood at No Expense Whatever of His Innocence

32: A

Marylandiad

Is Brought to Birth, but Its Deliverer Fares as Badly as in Any Other Chapter

33: The Laureate Departs from His Estate

1: The Poet Encounters a Man With Naught to Lose, and Requires Rescuing

2: A Layman's Pandect of Geminology Compended by Henry Burlingame, Cosmophilist

3: A Colloquy Between Ex-Laureates of Maryland, Relating Duly the Trials of Miss Lucy Robotham and Concluding With an Assertion Not Lightly Matched for Its Implausibility

4: The Poet Crosses Chesapeake Bay, but Not to His Intended Port of Call

5: Confrontations and Absolutions in Limbo

6: His Future at Stake, the Poet Reflects on a Brace of Secular Mysteries

7: How the Ahatchwhoops Doe Choose a King Over Them

8: The Fate of Father Joseph FitzMaurice, S.J., Is Further Illuminated, and Itself Illumines Mysteries More Tenebrous and Pregnant

9: At Least One of the Pregnant Mysteries Is Brought to Bed, With Full Measure of Travail, but Not as Yet Delivered to the Light

10: The Englishing of Billy Rumbly Is Related, Purely from Hearsay, by the Traveling Whore o' Dorset

11: The Tale of Billy Rumbly Is Concluded by an EyeWitness to His Englishing. Mary Mungummory Poses the Question, Does Essential Savagery Lurk Beneath the Skin of Civilization, or Does Essential Civilization Lurk Beneath the Skin of Savagery? -- but Does Not Answer It

12: The Travelers Having Proceeded Northward to Church Creek, McEvoy Out-Nobles a Nobleman, and the Poet Finds Himself Knighted Willy-Nilly

13: His Majesty's Provincial Wind-and Water-Mill Commissioners, With Separate Ends in View, Have Recourse on Separate Occasions to Allegory

14: Oblivion Is Attained Twice by the Miller's Wife, Once by the Miller Himself, and Not All by the Poet, Who Likens Life to a Shameless Playwright

15: In Pursuit of His Manifold Objectives the Poet Meets an Unsavaged Savage Husband and an Unenglished English Wife

16: A Sweeping Generalization Is Proposed Regarding the Conservation of Cultural Energy, and Demonstrated With the Aid of Rhetoric and Inadvertence

17: Having Discovered One Unexpected Relative Already, the Poet Hears the Tale of the Invulnerable Castle and Acquires Another

18: The Poet Wonders Whether the Course of Human History Is a Progress, a Drama, a Retrogression, a Cycle, an Undulation, a Vortex, a Right-or Left-Handed Spiral, a Mere Continuum, or What Have You. Certain Evidence Is Brought Forward, but of an Ambiguous and Inconclusive Nature

19: The Poet Awakens from His Dream of Hell to Be Judged in Life by Rhadamanthus

20: The Poet Commences His Day in Court

21: The Poet Earns His Estate

PART IV: THE AUTHOR APOLOGIZES TO HIS READERS; THE LAUREATE COMPOSES HIS EPITAPH

The Poet Is Introduced, and Differentiated

from His Fellows

In the last years

of the Seventeenth Century there was to be found among the fops and fools of the London coffeehouses one rangy, gangling flitch called Ebenezer Cooke, more ambitious than talented, and yet more talented than prudent, who, like his friends-in-folly, all of whom were supposed to be educating at Oxford or Cambridge, had found the sound of Mother English more fun to game with than her sense to labor over, and so rather than applying himself to the pains of scholarship, had learned the knack of versifying, and ground out quires of couplets after the fashion of the day, afroth with

Joves

and

Jupiters,

aclang with jarring rhymes, and string-taut with similes stretched to the snapping-point.

As poet, this Ebenezer was not better nor worse than his fellows, none of whom left behind him anything nobler than his own posterity; but four things marked him off from them. The first was his appearance: pale-haired and pale-eyed, raw-boned and gaunt-cheeked, he stood -- nay,

angled

-- nineteen hands high. His clothes were good stuff well tailored, but they hung on his frame like luffed sails on long spars. Heron of a man, lean-limbed and long-billed, he walked and sat with loose-jointed poise; his every stance was angular surprise, his each gesture half flail. Moreover there was a discomposure about his face, as though his features got on ill together: heron's beak, wolf-hound's forehead, pointed chin, lantern jaw, wash-blue eyes, and bony blond brows had minds of their own, went their own ways, and took up odd postures, which often as not had no relation to what one took as his mood of the moment. And these configurations were short-lived, for like restless mallards the features of his face no sooner were settled than

ha!

they'd be flushed, and

hi!

how they'd flutter, and no man could say what lay behind them.

The second was his age: whereas most of his accomplices were scarce turned twenty, Ebenezer at the time of this chapter was more nearly thirty, yet not a whit more wise than they, and with six or seven years' less excuse.

The third was his origin: Ebenezer was born American, though he'd not seen his birthplace since earliest childhood. His father, Andrew Cooke 2nd, of the Parish of St. Giles in the Fields, County of Middlesex -- a red-faced, white-chopped, stout-winded old lecher with flinty eye and withered arm -- had spent his youth in Maryland as agent for an English manufacturer, as had his father before him, and having a sharp eye for goods and a sharper for men, had added to the Cooke estate by the time he was thirty some one thousand acres of good wood and arable land on the Choptank River. The point on which this land lay he called Cooke's Point, and the small manor-house he built there, Malden. He married late in life and conceived twin children, Ebenezer and his sister Anna, whose mother (as if such an inordinate casting had cracked the mold) died bearing them. When the twins were but four Andrew returned to England, leaving Malden in the hands of an overseer, and thenceforth employed himself as a merchant, sending his own factors to the plantations. His affairs prospered, and the children were well provided for.

The fourth thing that distinguished Ebenezer from his coffeehouse associates was his manner: though not one of them was blessed with more talent than he needed, all of Ebenezer's friends put on great airs when together, declaiming their verses, denigrating all the well-known poets of their time (and any members of their own circle who happened to be not on hand), boasting of their amorous conquests and their prospects for imminent success, and otherwise behaving in a manner such that, had not every other table in the coffeehouse sported a like ring of coxcombs, they'd have made great nuisances of themselves. But Ebenezer himself, though his appearance rendered inconspicuousness out of the question, was bent to taciturnity. He was even chilly. Except for infrequent bursts of garrulity he rarely joined in the talk, but seemed content for the most part simply to watch the other birds preen their feathers. Some took this withdrawal as a sign of his contempt, and so were either intimidated or angered by it, according to the degree of their own self-confidence. Others took it for modesty; others for shyness; others for artistic or philosophical detachment. Had it been in fact symptom of any one of these, there would be no tale to tell; in truth, however, this manner of our poet's grew out of something much more complicated, which warrants recounting his childhood, his adventures, and his ultimate demise.