The Soul Mirror (15 page)

Authors: Carol Berg

Tags: #General, #Fiction, #Fantasy, #Fantasy fiction

More than tenday gone and I’d learned nothing to explain my sister’s death. I had applied to every undersecretary in the steward’s office and the chancellor’s, as well as to the Temple Minor and the king’s First Secretary, for permission to visit Ambrose, but no one had been able or willing to help. Though I scoured the royal library, hoping to discover what poisons might destroy a woman’s mind or how else such a thing might be accomplished in the matter of a day, I had found no answers. Neither sleep, study, exercise, nor conversation had provided relief for the agitation that afflicted me when thrust among strangers. Bees might have been nesting in my ears.

On the long afternoons I roamed the edges of the queen’s salon or sat by a window, trying to stay inconspicuous and avoid screaming with boredom. I knew I should speak to people, try to make acquaintances, or at least convince someone I was not leprous. This was my life now, and I needed to make something of it. I listened to gossip and collected rumors of more strange incidents in the city—including a violent whirlwind that had destroyed the Plas de Gierete, the Punishment Square where criminals were publicly whipped or executed.

Every day I swore to find someone among the women who might enlighten me about Lady Cecile or Duplais or exactly what services the mage Dante provided for the queen. But whenever one of the less-intimidating ladies in the room was between conversations, my mouth went dry and my head seemed entirely abandoned by any idea worth expressing.

I needed to see Ambrose. Perhaps if I could pour out the tale of these events, the two of us together might make some sense of them.

A FEW DAYS AFTER MY unsettling encounter with the mage, I dawdled too long in my bedchamber, writing a letter to Bernard and Melusina. As I hurried down the window gallery, late for the first of a flurry of evening engagements, none of which I anticipated with pleasure, a light touch on my shoulder spun me around so fast I near burst my skin.

“Damoselle de Vernase. Would ye come with me, damoselle?” A trim young serving man whipped his hands behind his back, only to pull one out again to dash a lock of yellow hair from his eyes. “My master would have a word with you.”

“Who are you? Who is your master?” My address was much too abrupt, but if he answered Dante, I was sure to heave up my lunch.

The young man grinned cheerfully. “I’m Heurot, damoselle, saints please ye for asking, gentleman’s attendant and aide to Sonjeur Portier de Savin-Duplais, Administrative of Her Majesty’s household. My master bids you report to his chambers as you are required.”

Every day since the humiliating spectacle at the Arothi tribute ceremony, I had expected Duplais’ summons. Hoped for it, once I’d accepted him as my only route to Ambrose. I’d have damned pride and sought him out, but my time had been occupied at every hour he was available. And again tonight . . .

“I’m expected by the Ducessa de Blasencourt just now, Heurot. Tell Sonjeur de Duplais that I’ll attend him after the presentation tonight.”

Heurot looked distressed. “But, damoselle . . .”

“Later, I promise.”

The gloomy afternoon had grown chilly and threatening as I hurried through the inner courts toward the west wing. I was to sit an early supper with the other maids of honor and meet with Lady Cecile for another hour of frustrating nothing. The evening’s culmination was to be our formal presentation to Queen Eugenie. The prospect was unbearable. With an ache as sore as any wounding, I longed to be home.

Halfway down the portrait gallery leading to Cecile’s apartment, a youthful figure hovered beneath a greater-than-life-sized image of Philippe de Savin-Journia, my king and goodfather. The youth popped to attention as I passed. “Damoselle, please wait.”

“Heurot! How did you—? I told you I’ve engagements for the next few hours.”

“My master does sincerely wish a word with you, damoselle. He is most insistent.”

Resolution faltered, then hardened into a different shape. “All right. Give me a few moments.”

The women were picking at poached pears and lettuce when I was shown in and promptly begged leave to withdraw with a headache. Though I believed the lie must be written on my face for all to see, none of our three mentors seemed particularly surprised. Lady Patrice flared her nostrils in disapproval, but she could hardly object. The other maids of honor, including her especial favorites, fostered headaches enough for a regiment of unhealthy young women.

“We’ll see you at the presentation, then,” said Lady Cecile. “Angels’ peace, Anne.”

I was surprised when she rose from the table and escorted me to the door. As I lowered my guilty gaze and bade her a peaceful evening, she pressed a small leather-bound book into my hand. “Read this for our next meeting,” she said quietly. “Be prepared to discuss it. I believe it relevant to our discussion of several days ago.”

My eyes shot up. Her smooth, elegant forehead was seamed with worry, and her usually rosy complexion had a dreadful gray cast to it. A damp sheen coated her upper lip. “My lady—”

“Be off now.” In a swirl of plum satin, she returned to the others, beckoning her maidservant, Slanie, to close the door behind me.

Alone outside the door, I examined the worn little book. The title, scribed on red leather in faded gold lettering:

A Brief History of the Demesne Gautier.

A Brief History of the Demesne Gautier.

Heaven’s gates!

Gautier

was the name on Lianelle’s books of sorcery! I was instantly torn. Heurot waited in the gallery, ready to take me to Duplais. My yearning to hold my brother in my arms, to comfort him in his lonely prison and share the dreadful events of the past month had swelled to bursting, and the only way I could see to ease that ache led through the queen’s administrator. But this book . . . Dates and names and lists, sketched maps, and genealogical charts tantalized me as I thumbed through it. An entire section was titled “Collegia Magica de Gautier.” Surely this book was enlightenment.

Gautier

was the name on Lianelle’s books of sorcery! I was instantly torn. Heurot waited in the gallery, ready to take me to Duplais. My yearning to hold my brother in my arms, to comfort him in his lonely prison and share the dreadful events of the past month had swelled to bursting, and the only way I could see to ease that ache led through the queen’s administrator. But this book . . . Dates and names and lists, sketched maps, and genealogical charts tantalized me as I thumbed through it. An entire section was titled “Collegia Magica de Gautier.” Surely this book was enlightenment.

But the needs of the living must trump the concerns of the dead, no matter how dreadfully, hurtfully, they had passed beyond the Veil. I stuffed the little volume deep into the pocket of my underskirt. First I must persuade Duplais to get me into Spindle Prison. Then be “presented.” Then I would delve into Lady Cecile’s book.

“My master says he’s chosen a venue less likely for interrupting,” said Heurot cheerfully, as we bypassed the turning to Duplais’ office chamber.

I was skeptical. Even more so when the young manservant led me down and down into a gloomy bricked passage that must penetrate Merona’s bedrock. Certainly it was a season removed from the autumnal warmth upstairs. I wished I’d brought a shawl.

“Here, damoselle.” Heurot indicated an open doorway, snapped an inexpert bow, and hurried back the way we’d come.

I had the impression of a spacious room, but in truth I could make out nothing but two chairs drawn close to a well-grimed hearth. A small fire snapped in the grate, creating a modest circle of light and warmth. The room’s most noticeable feature was an enveloping quiet. For the first time since riding into Merona, I could hear myself think.

“Divine grace, damoselle.” Duplais stepped out of the shadows behind the high-backed chair. Exposing his marked left hand, he sketched a bow. “Please sit,” he said, indicating the chair opposite his.

I exposed my Cazar mark and sat.

Duplais remained standing. “Are you well, damoselle? Settling in? Our journey was not too taxing?”

Had he lost his mind? “I’m well recovered, sonjeur, and becoming familiar with my duties.”

That seemed to satisfy his scheduled allotment of banter. He picked up a few folded papers from a shelf above the hearth, passed them to me, and retreated behind his own tall chair, where the firelight could not reach his face. Only his slender hands remained visible, resting on the back of the chair, left hand marked, the right pitted with small angry scars.

I glanced at the papers. Letters, addressed to me. Seals broken.

Heat, nothing to do with the fire, suffused my cheeks.

“The king insists,” he said, before I could speak. “I take no pleasure from it. Take the time to read, if you like.”

To wait and read the brief missives later would demonstrate more self-command, but I could not bear the thought that this man knew more of my business than I did. So I read.

A letter from the temple minor in Seravain stated simply that the verger of the Seravain deadhouse had issued a death warrant for

Lianelle de Vernase ney Cazar, age seventeen years, dead by calamitous incident

. The warrant would be forwarded to the temple major at Tigano, at which time the family of the deceased could apply to Tigano’s verger for a sanctified tessila.

Lianelle de Vernase ney Cazar, age seventeen years, dead by calamitous incident

. The warrant would be forwarded to the temple major at Tigano, at which time the family of the deceased could apply to Tigano’s verger for a sanctified tessila.

“I have taken the liberty of notifying the verger at Seravain to forward your sister’s warrant to Verger Rinaldo at our temple minor here instead,” said Duplais.

I did not thank him.

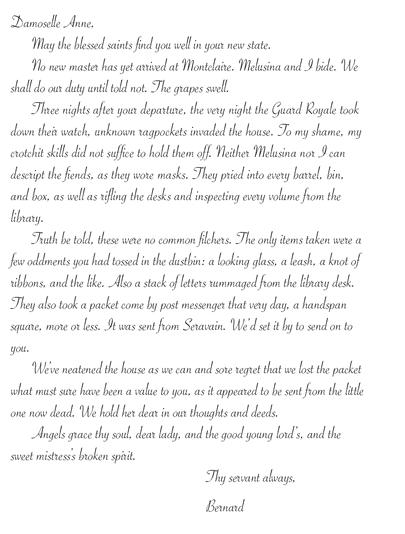

The second letter, somewhat longer, was from Bernard, scribed with his usual careful lettering and direct prose.

HORRID TO IMAGINE BERNARD AND Melusina beset by men like those who’d accosted Duplais and me in the wood. The stolen oddments were all from Lianelle’s room—trinkets from her childhood, things she had tried to work spells on before she went to Seravain. Nothing of value. Nothing I wanted to keep. She had given me the shell-backed looking glass years ago, but I had returned it, as the glass was poor quality. Using it left me dizzy. The packet, however . . .

“So they found what our masked bandits were seeking in your luggage.” Duplais echoed my thoughts so clearly, it was startling. “I suppose you’ve no idea what these

oddments

might be, or the letters or the packet from your sister. A book, possibly?”

oddments

might be, or the letters or the packet from your sister. A book, possibly?”

Though I would rather yield nothing to the hateful man, I would cooperate. I was determined to learn what he knew of Lianelle’s death, and I needed his approval to visit Ambrose.

“The only letters left in the drawer were my father’s correspondence with Germond de Vouger, a gifted man of science. They’re valuable to those who treasure the power of intellect and scientific advancement. Perhaps they think to sell them.”

“I know of de Vouger. A physicist and astronomer. He was a friend of your father’s?”

“Not a friend, not in the personal sense. I don’t know that they ever met. But they corresponded for many years about the role of science in society and the imperative to stretch the boundaries of exploration, both in the world and in the mind. And about de Vouger’s own discoveries, naturally. Nothing treasonous, you can be sure.”

Duplais tucked that away without expression. “And the packet?”

“My sister hoped to sit for her adept’s examinations this winter and feared she wouldn’t be allowed to study what she needed. The librarian despised her. So from time to time she sent books home to read on holidays. How could I know which one? What could be so important about her books?”

“Books are valuable and fragile. They can be damaged by shuffling around the countryside. Or lost. Or passed on to a villain who should not have them—a soul-eating villain who recruits his own daughters into his dangerous games.”

Duplais’ distaste for despicable parents might recommend him if I didn’t suspect him and his mage of harming my mother for

their

own purposes. Had his dogged pursuit of the king’s enemies become a campaign for his own private gain? A failed sorcerer, a king’s cousin of incisive logic and intelligence reduced to assigning apartments for ladies-in-waiting, might be willing to use anything, even this rogue Dante, to gain access to my father’s secrets.

their

own purposes. Had his dogged pursuit of the king’s enemies become a campaign for his own private gain? A failed sorcerer, a king’s cousin of incisive logic and intelligence reduced to assigning apartments for ladies-in-waiting, might be willing to use anything, even this rogue Dante, to gain access to my father’s secrets.

“What information might be of such desperate interest to my father?” I said, acutely aware of Lady Cecile’s book in my pocket. “Or to his rivals, if your theories about those highwaymen at Vradeu’s Crossing are correct?”

“That’s certainly the question, is it not?” he said. “What were these other articles the brigands took from Montclaire?”

“I discarded many items of little or no value before we left. As you well know, I refused to leave any of my family’s personal belongings for the new Conte Ruggiere.”

I was as curious as Duplais. Was it the specific artifacts Lianelle had made from the books that they hunted . . . or was it

anything

she had touched?

anything

she had touched?

Other books

More Awesome Than Money by Jim Dwyer

Manly Wade Wellman - Novel 1952 by Wild Dogs of Drowning Creek (v1.1)

What Alice Forgot by Liane Moriarty

The Uninnocent by Bradford Morrow

Asking For Trouble by Ann Granger

Dark Xanadu by van Yssel, Sindra

The Black Key by Amy Ewing

A Taste of Magic (A Sugarcomb Lake Cozy Mystery Book 1) by Alaine Allister

Taste for Blood by Tilly Greene

The Mall by S. L. Grey