Read The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment And The Tuning Of The World Online

Authors: R. Murray Schafer

The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment And The Tuning Of The World (43 page)

Man also inscribes human rhythms onto the physical world in manual work. Many tasks such as scything, pumping water or pulling ropes cannot be performed unless they follow the breath pattern. Other rhythms—hammering, sawing, casting—take their measure from the arm; still others like knitting or playing a musical instrument are dictated by the motions of the fingers. In instruments like the foot-pedal lathe or loom, hand and foot are united in smooth complementary motions.

Leo Tolstoy describes how Russian peasants could scythe a field together in perfect synchronization without a trace of misdirected energy. Let the description speak for all labor in which body motion, working tool and material are perfectly united.

He heard nothing but the swish of scythes, and saw … the crescent-shaped curve of the cut grass, the grass and flower heads slowly and rhythmically falling before the blade of his scythe, and ahead of him the end of the row, where the rest would come. …

The longer Levin mowed, the oftener he felt the moments of unconsciousness in which it seemed that the scythe was mowing by itself, a body full of life and consciousness of its own, and as though by magic, without thinking of it, the work turned out regular and precise by itself. These were the most blissful moments.

Another biological tempo which relates significantly to the acoustic environment is that of the resolving power of the sense receptors. In humans this hovers around 16 to 20 cycles per second. It is in this frequency range that a series of discrete images or sounds will fuse together to give an impression of continuous flow. Film employs 24 frames per second in order to avoid flicker. As far as aural perception is concerned, a rapid rhythmic vibration will gradually assume an identifiable pitch at about 20 cycles per second. Thus, as the tempo of human activities increases, the rhythms of foot and hand are mechanized, first into the rough, “grainy” concatenation of the Industrial Revolution’s first tools, and finally into the smooth pitch contours of modern electronics. The resolving power of the senses makes it possible to turn some of the nervous agitation of the soundscape into drones which, being less turbulent to the ears, tend to have a pacifying quality.

Within the framework of our experience, the audible metrical divisions of heart, breath and foot, as well as the conservational actions of the nervous system, must be our guide against which we arrange all the other fortuitous rhythms of the environment around us.

Rhythms in the Natural Soundscape

The environment contains many sets of rhythms: those dividing day from night, sun from moon, summer from winter. Though these may not provide audible pulsations, they do have powerful implications for the changing soundscape.

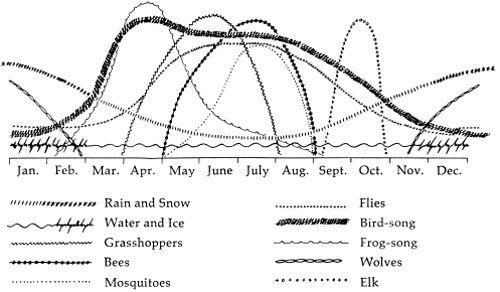

To all things there is a season. There is a time for light and a time for darkness, a time for activity and a time for rest, a time for sound and a time for not-sound. It is here that the natural soundscape provides a clue, for if we could register all the periods of rest and activity among natural sounds, we would observe an infinitely complex series of oscillations as each activity rises and falls from exertion to slumber, from life to death. I have put together a rudimentary chart of some of the more prominent natural features of the British Columbia soundscape in order to suggest the shape of the annual cycle. Like that of every other part of the world, it creates a vivid vernacular composition following a general cyclic rule, a composition in which each instrumentalist knows when to perform and when to listen quietly to the themes of others.

The cycles of the natural soundscape of the west coast of British Columbia showing the relative volume of sounds

.

Man plays his role in this cycle also, or at least he did when he respected the agrarian calendar. Planting and harvesting contributed rich patterns of seasonal sounds to the country soundscape. And in man’s activities too, there were periods of sound and silence—for we were then better listeners, and the forest and field provided acoustic clues vital to survival.

This healthy give and take between sounds in the natural soundscape is disappearing from the modern urban world. When the factories of the Industrial Revolution swivel-moored workers to the same bench for alifetime, seasonal variations vanished. The factory also eliminated the difference between night and day, a precedent which was extended to the city itself when modern lighting electrocuted the candle and night watchman. If we were to make a continuous recording on a downtown street of a modern city, it would show little variation from day to day, season to season. The continuous sludge of traffic noise would obscure whatever more subtle variations might exist.

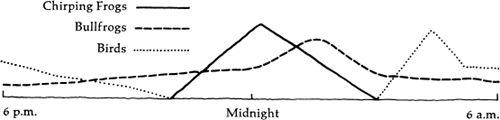

Let me instead analyze a recording we made at a rural site near Vancouver. The recording was made by a small pond over a twenty-four-hour period on summer solstice. The accompanying diagram shows the cir-cadian cycle clearly, and sound level readings, taken while the recording was in progress, show the general ambient sound level together with levels of some of the predominant sounds recorded. The loudest of the continuous sounds was that of aircraft, and charts we made during the recording show that this sound was present over the rural setting for an average of 32 minutes per hour during the day and evening.

Aside from the aircraft, there were three main groups of performers: birds, bullfrogs and chirping frogs. The most salient—and for the recordists, the most beautiful—moments of the recording came during the complementary crossovers at dawn and dusk between the chirping frogs and the birds. At the very moment when the first bird was heard (3:40 a.m.) the chirping frogs became silent, not to return until dusk, when the last bird was trailing off. We can have no idea of the significance of this for the performers; we can only note that as the voices of both sets of performers occupy a similar high-pitched range, they would, if sounded together, tend to mask one another, thus reducing the clarity obtained by vocalizing in rotation. The bullfrogs, on the other hand, with deep voices, offer no competition for either performer. They continued to croak intermittently through both day and night.

A similar restraint is noticeable in the gathering of the dawn chorus. Following the first bird, the chorus gradually rose in complexity and intensity, peaking after about half an hour, then settled back to sustain itself on a less frenzied level throughout the day. Of special interest to us was the manner in which each species woke up as a group, sang vibrantly for a few moments, then seemed to fall back as another species came forward. The effect is analogous to the different sections of an orchestra entering separately before combining in the total orchestration. I have found no ornithologist to provide an explanation for this effect, though it is very clear on our recording.

The long-term shape of the other groups of performers is similar, swelling in volume, then decreasing again to inactivity; but in each case this oscillation takes place over a different period of time: about 5 hours for the chirping frog group, about 18 hours for the birds and 24 hours for the bullfrogs.

The two frog groups achieve their peak activity by different means. In the bullfrog group the number of frogs remains constant and each individual frog increases or decreases its vocal activity. In the chirping frog group each individual frog shows little variation in vocal activity but the climax is reached after midnight when the number of active frogs is greatest.

The short-term time pattern of the two frog groups shows a further difference. The chirping frogs sing together in choral interludes separated by silent periods. One or two frogs will start, and almost immediately all will join in. The synchronization with which, after a moment or two of busy activity, they will all stop together is even more remarkable. The bullfrogs, on the other hand, do not operate as a group at all; each frog croaks quite independently, though at the period of their peak activity, their sounds may overlap in ragged rhythmic clusters.

The sounds of frogs and birds are not the only ones on the recording, and though the others do not lend themselves to such rapid analysis, they too have their own unique rhythmic patternings. To make this clearer we mixed an abbreviated tape of the summer solstice recording, selecting two minutes out of each hour, and in this the circadian rhythms can be heard very clearly. We have used the same technique on numerous other occasions in different locations, and have come to regard it as one of the greater learning experiences of recent years.

Rhythms in Village Life

Circadian and seasonal rhythms are observable in human settlements also, but they are strongest in small towns and villages where life is more apt to be regulated by common activities. It was in order to study the dynamics of the village soundscape that we undertook an investigation of five European villages in 1975. Here we were able to document how village life revolves around important community signals such as church bells or factory whistles. We discovered, for instance, that not only do they punctuate village life but their advent precipitates chains of other sounds in quite orderly recitals. For instance, an early morning factory whistle will be preceded by commotion in the streets and followed by commotion in the factory and stillness in the streets. By walking through the various parts of the village several hours each day and making lists of all the sounds heard, we were later able to show the way in which many sounds followed definite rhythmic patterns: for example, the women’s voices dominate the streets at certain times of the day and men’s or children’s at other times. It was also possible to show how the rate of traffic growth in a village stimulates a corresponding growth in the other sounds, but, surprisingly, a

reduction

in the variety of sounds heard—an important finding which supports earlier statements in this book. It is difficult to illustrate these matters without elaborate statistical charts, so it is best to refer the interested reader to the study itself, passing on to make our point that village soundscapes have highly pronounced rhythmic patterns by means of a simpler illustration.

Cembra is an Italian mountain village north of Trento and just below the Tyrol. Tucked far up a valley, connected to the outside world by a single, winding, mountain road, Cembra was the only village we studied in which the number of human sounds in the streets outnumbered those of motorized traffic. Until well into the twentieth century, Cembra was virtually self-supporting, producing its own food, goods and services. As a result it developed a highly active and self-sustaining social life. Entertainments, church feasts and other activities were plentiful and were strongly acoustic in character.

Winter was the quiet season but was by no means devoid of its ceremonies. On St. Lucia’s and St. Nicholas’s Day (December 5) boys would go around the village ringing hand bells and banging things with chains. Every so often they would stop to sing the verse of a song about the saints. On Christmas Eve they returned to sing carols in the streets. At 11:55 p.m. on New Year’s Eve, a special bell was rung, echoed the next day with the firing of cannons, or

mortaretti

, as they are called. These were small, 15-centimeter-diameter weapons and they seem to have been fired off on almost all possible occasions and certainly at all religious festivals. I have mentioned before the intimate relationship between the church bell and the cannon and how throughout European history the same metal was poured into one shape, then into the other. With the

mortaretti

, the relationship is made explicit once again.

The relative quiet of winter was shattered on the evening of March 1 with a custom called 77

Tratto Marzo

, when crowds of youths would climb to different peaks in the hills behind the village. There they would divide into groups, light fires and, using cardboard megaphones, call names of those likely to be married in the coming year. If the marriage was a real possibility, cannons were fired. If the match was a joke, horns would be blown instead.