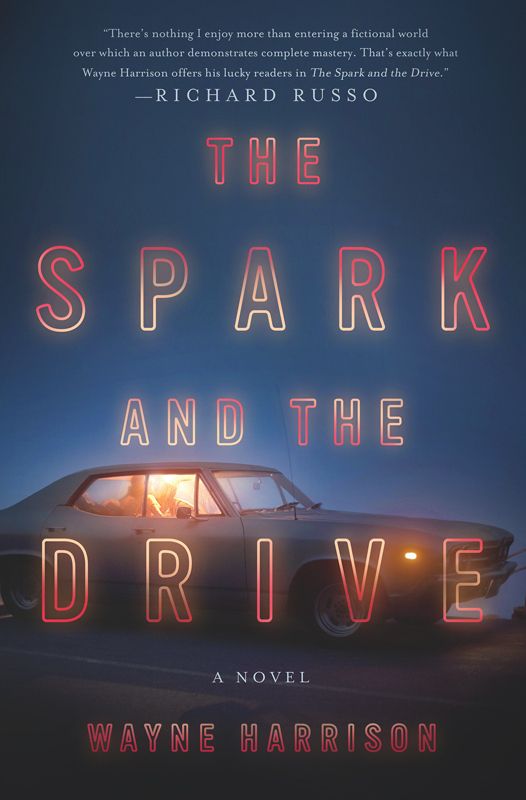

The Spark and the Drive

Read The Spark and the Drive Online

Authors: Wayne Harrison

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

For the beautiful women in my life: Caye, Sabrina, and Josie

Contents

I see us painting the shop together. I smell the sharp, gratifying blend of latex and gasoline. It’s 1985, and Nick has offered me a hundred dollars to stay and help. “Walls only, three coats,” he says, lugging eight gallons of platinum gray.

Into the first bay we pile disassembled pegboard, fan belts, hoses, wire sets. Nick orders a Meaty Supreme from Vocelli’s, and when Mary Ann mentions beer I run out the side door to Lenny’s Liquor Locker on the corner. I’m seventeen but formidable in my button-down Dickies shirt and dungarees; Lenny Jr. serves me even as I drop a hill of ones on the counter sign that says

NO ID NO SALE

.

We spread tarps, pry off lids, fill the roller trays. Nick spins on an extension pole and then rolls so fast a gray mist sprinkles his white Owner shirt. He overlaps where Mary Ann has edged and touches the ceiling a few times. Breathing hard, he drops the roller on the tarp and lights a cigarette, pondering the rest of the wall, the thirty feet of it left to paint.

Mary Ann smooths over his lap marks, and it’s their quiet together that makes me feel safe. You hope for such assurance around your own parents, though mostly I remember my father’s light jabs, my mother’s retaliations, words that hook in and stay.

“I thought you were good at everything,” Mary Ann says, on tiptoes stretching for the border tape.

Nick sees where he’s gone over half the wall thermostat. He grins as when a random engine skip tries to outsmart him. “I get why Van Gogh cut his ear off.”

“I like your ears,” Mary Ann says. “Let’s keep those. Maybe one of your big ugly hands.”

And she doesn’t move even when his choking hands come around her throat.

“Now you did it,” he says. “Now you’re in trouble.”

When I look again at my own roller, fat gray drips have run down to the floor.

* * *

It’s almost midnight when we finish the first coat, and Nick wants to speed up the drying. The tank of the waste-oil heater has been empty since spring, and I roll over the thirty-gallon catch from the oil-change bay and pump it into the heater tank. But the walls are tacky even after the thermostat hits ninety degrees.

“It’s baking,” Mary Ann says, fanning her face with a

Motor Trend

. “We’re all going to bake in here.” She gazes drowsily and finds the convertible Camaro that has been left for the weekend. “Well, hey there,” she says, and walks over to it.

The Camaro is parked in the center bay, farthest from the wet walls, a rare ’67 Rally Sport with hideaway headlights and chrome rally wheels. It was a ground-up restoration, and under a buzzing light panel, the cobalt blue paint is like looking into the polished ice of a glacier. The other muscle car shop in town passed up the job—a collector’s car plagued by intermittent complaints—and I didn’t blame them. Most mechanics come to accept that some cars just aren’t fixable. But Nick’s mind is boundless in its capacity for learning and wonder, and he has yet to open the hood on an unfixable car. I’m still hanging on to wonder myself, and it hasn’t escaped my awareness that this is part of why Nick likes me.

Mary Ann pushes her fingers in through the Camaro’s grille to pop the latch. She lifts the hood and unexpectedly turns to me. “Have you heard about the Pacific Coast Highway, Justin?”

“I think so,” I say.

“It’s where they make Porsche commercials,” Nick says. “A lot of cliffs and hairpins.”

“If you take a woman there in a convertible, she’ll be putty in your hands.”

“Sure,” I say. “That was out in Oregon, right?”

“It’s worth the plane ticket, believe me.” She leans over the fender carefully, so that her tank-top shirt and jean rivets don’t touch the paint, a careful yoga-like bend. Nick doesn’t ask what she’s doing, so I don’t ask, and when he finishes his cigarette and walks up to the Camaro, I pace myself not to pass him. Together we look down just as she’s pulling the speedometer cable away from the transmission.

“Voila,” she says, leaning back, and the car is set to drive with no miles recorded.

* * *

From the bay windows a pearly light blooms out into the rumpled dark of the city. Deep in the backseat vinyl, I can feel the wind on a windless night as Nick eases out of the parking lot with the top down.

Wolcott Avenue opens to four lanes, and finding me in the rearview mirror Nick says what I’ve never heard him say before: “Buckle up.” I dig for the lap belt and send the tongue into the buckle with a fortifying click before I can breathe again. With the clutch in Nick revs the engine twice, a perfect machine-gunning of the valves he’s lapped and polished, and drops the shifter to second gear. When he dumps the clutch the sudden blast of air seems to be what throws me back, though of course it’s the g-force, that awesome multiplier of weight, and then we’re sideways, fishtailing. Nick chirps the tires in third gear and again in fourth. I know the police are out there, they’re just not here, and after all the cars he’s saved, Nick has surely earned immunity from traffic crimes. I whip around the backseat, anchored only by the waist, invulnerable and reeling with the sudden flush of complicity.

On Eden Avenue Mary Ann slides under Nick’s arm. When he presses in the clutch she shifts smoothly through the gear pattern, and we ride over narrow hilly streets whose neighborhoods arise as odors in the treeless air—hot, dusty fire escapes and cigarettes from people out this late smoking on them, steaming aluminum fins of little AC units. Farther north, where the buildings are cared for, smells of cut lawn as we approach the quiet and leafy Waterbury Green.

I can hear the fountain before I see it, under the great brass horse, and above us the Basilica of the Immaculate Conception is spotlit from the ground. Mary Ann and Nick talk softly, their mellow tones a kind of tender anthem for the night. Then she kicks off her sandals, and as Nick slows the car she stands on the passenger seat, facing backwards—facing me. Her paint-speckled Sassons are threadbare at the knees, and his arm wraps around her thigh. Her face is radiant, her wind-strained eyes searching the night as if from the bow of a ship. On the balmy sidewalks, anyone laying eyes on her might fall in love. I crane my head back and find the Big Dipper canted as if to spill its potion over the gothic spires of St. John’s on the Green.

“You try it, Justin,” she says.

The speedometer needle is lifeless at nine o’clock, and I guess our speed to be an easy twenty or twenty-five. Nick feathers the gas so that it is no harder to stand on the tucked vinyl than it would be standing on an airplane. And we’re aloft and banking softly. The air is cooling. We are in it and waiting for its slight gusts, and feeling the hum of the slow engine and driveshaft turning under our bare feet. Nick makes the loop again so easily we barely sway.

“What do you think?” Mary Ann says.

The word that comes to me bypasses my brain, is simply there from unthinking organs, and it is both for this ride and for the entirety of the summer.

Glorious.

But I’m shy with her and manage only a shrug. We take another lap with our eyes closed before Nick drifts us gently to the curb, and she floats down to kiss him.

* * *

The vision ends there, and I stay with it until the same bristle comes, the same bold dreams of transformation. I want to speak, to tell her the word she wanted, and to talk to them with the words I have now, as the husband, the father, the man at last. But the man can’t change the boy, and anything I tell them they couldn’t hear.

PART ONE

1.

Road Rage

magazine, in a commemorative issue that mourned the death of the American muscle car—killed by the Environmental Protection Agency—ran a feature on Nick Campbell in 1983. The article was two years old when I started my internship, and I liked to reread it, framed and dusty on the counter, as I stirred powdered creamer in my coffee. I almost had it memorized:

Ten years after the EPA came down on Detroit like the church on Galileo, we still see no renaissance of horsepower on the showroom floor. With more repair shops catering to economy cars and imports, high-performance rebuilds and modification remain in the hands of a dedicated few. Recently, we sought out this dying breed of mechanic in the depressed factory town of Waterbury, Connecticut, and discovered one of the very best.

The journalist hadn’t identified himself when he handed Nick the keys to a cherry ’68 Daytona. He asked for an overhaul that would boost factory output by thirty horsepower, a request that had gotten him laughed out the door at two previous shops.

But Mr. Campbell dreamed through a full orchestra of internal combustion cause and effect: shaving the cylinder head this much meant boring a carburetor jet this much meant extending cam duration this much, meant swapping these pistons for those, this intake for that—all of it drawn to a final composition in his head before I even signed the estimate.

The engines we saw were mostly small blocks, punctuated by a Tri-power GTO or a rat-motor Corvette—or, rarely, a true exotic like a Hemi Superbird. At seventeen, I was as dumbfounded as anyone to find myself touching these cars intimately, peering inside their complicated souls.

After two years in vocational high school, I understood the general repair mechanic to be the perfect masculine blend of strength and intelligence. Real men had a natural respect for mechanics, primarily for specialty mechanics, which we all were. Ray Abbot, in his fifties, was the oldest. He was frank and cagey with customers, though he held a deep, wholesome respect for their high-compression engines. He lived alone, was estranged from his kids, and lumbered on irascibly, scorning potential friends.

Bobby Stango had been hired on parole and was epitomized by a biker T-shirt he often wore in to work.

TREAT ME GOOD, I’LL TREAT YOU BETTER,

it said.

TREAT ME BAD, I’LL TREAT YOU WORSE.

With his pierced ear and handlebar mustache, he made even a starched-collar uniform look badass, pillows of tattooed muscle bulging against the chrome snaps. There was a willingness to fight that pervaded his words and gestures, even his laughter, and he gave you bear hugs if he liked you. I wondered if this were a natural disposition, or if prison had taught him what each day of freedom was worth.