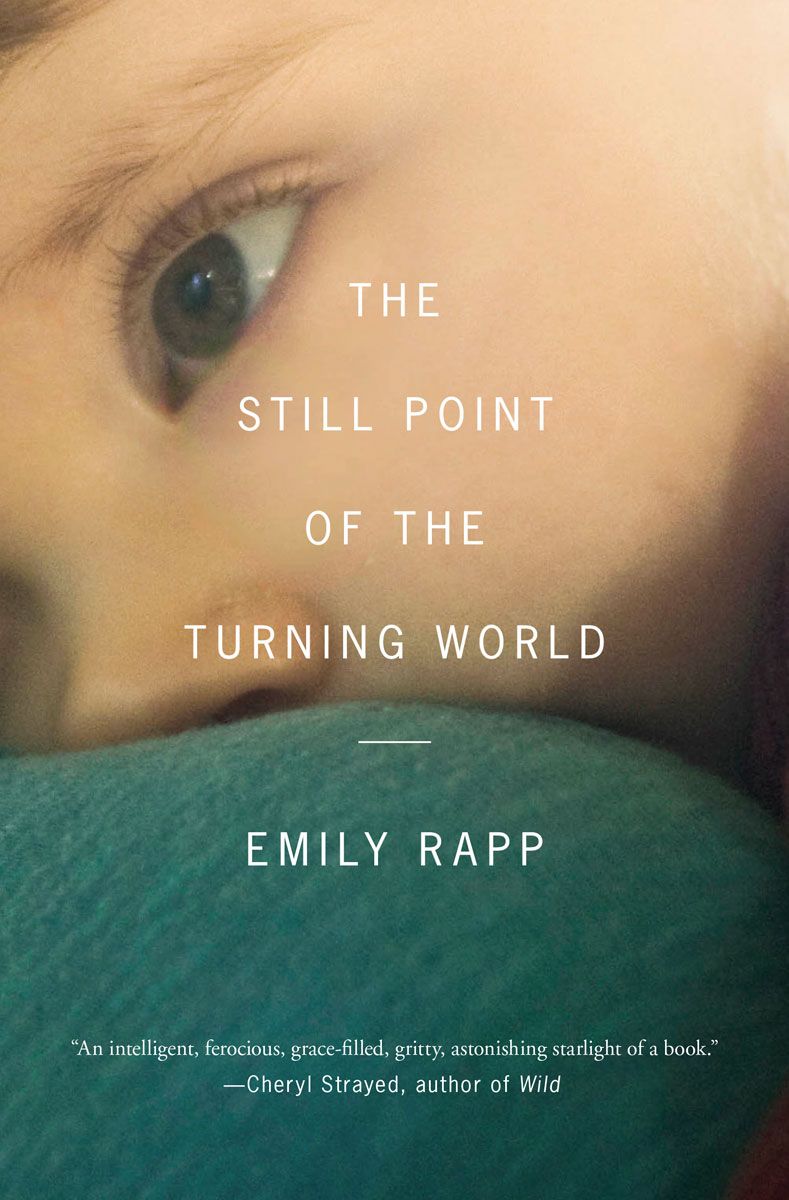

The Still Point Of The Turning World

Read The Still Point Of The Turning World Online

Authors: Emily Rapp

ALSO BY EMILY RAPP

Poster Child

THE PENGUIN PRESS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

•

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario M4P 2Y3, Canada (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

•

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

•

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

•

Penguin Group (Australia), 707 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3008, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

•

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi–110 017, India

•

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

•

Penguin Books (South Africa), Rosebank Office Park, 181 Jan Smuts Avenue, Parktown North 2193, South Africa

•

Penguin China, B7 Jiaming Center, 27 East Third Ring Road North, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100020, China

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices:

80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published in 2013 by The Penguin Press,

a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

Copyright © Emily Rapp, 2013

All rights reserved

Permissions

constitutes an extension of this copyright page.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA

Rapp, Emily.

The still point of the turning world / Emily Rapp.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-101-60585-1

1. Rapp, Emily—Biography. 2. Tay-Sachs disease—Patients—Biography. 3. Terminally ill children—Family relationships—Biography. I. Title.

RJ399.T36R37 2013

618.92'8588450092—dc23

[B]

2012039516

No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

Penguin is committed to publishing works of quality and integrity. In that spirit, we are proud to offer this book to our readers; however, the story, the experiences, and the words are the author’s alone.

FOR RONAN, ALWAYS

Contents

I love the handful of earth you are.

—Pablo Neruda,

100 Love Sonnets

1

T

his is a love story, which, like all great love stories, is ultimately a story of loss. On January 10, 2011, my husband, Rick, and I received the worst possible news: that our son, Ronan, then nine months old, had Tay-Sachs disease, a rare, progressive and always fatal condition with no treatment and no cure.

I had been worried for some time. Ronan was experiencing developmental delays, missing important milestones. I would rush home from work each day hoping he’d started to crawl or had said his first word. He was the same sweet, happy, gurgling baby—but that was the problem. He was the same at nine months old as he had been at six months. Our pediatrician suggested that we rule out any vision problems, so we drove from our home in Santa Fe to the pediatric ophthalmologist’s office in Albuquerque.

I sat in the examination chair as the eye doctor, a short, friendly man with black glasses, played cartoons for Ronan on his iPhone and flashed a series of lights in Ronan’s eyes. “He’s got good fixation,” he said. Ronan squirmed in my lap.

Great,

I thought,

he can see.

But behind this feeling of relief was a surge of panic—why, then, was he having these delays? I handed Ronan to Rick and sat in a chair nearby.

“Let me just check his retinas,” the doctor said, and hit the lights. I could see Ronan’s little eyes flash in the dark, and then Rick’s. The doctor carefully approached Ronan and peered into his eyes using a special light.

“Oh, boy,” the doctor said. “Oh, boy” was what my father had said when the doctors told my parents about my birth defect, which resulted in the amputation of my left foot. I gripped the sides of the chair and felt the floor drop away. The doctor flipped on the lights and said, “I’ve only seen this one other time.”

“What is it?” I asked, but I could see from his face that it was disastrous.

“Hey, little guy,” Rick said, and turned Ronan to face him.

“Rick,” I said. My hands were sweating, trembling. “Rick!”

“He has cherry-red spots on the backs of his retinas,” the doctor continued. “I’ve only seen this one other time in fifteen years of practice. It’s Tay-Sachs.” He paused. “I am so sorry.”

“What’s that?” Rick asked calmly, but then he quickly had to attend to me because I was wailing. I had wet my pants. The doctor calmly called for a nurse.

“I was tested!” I shouted. “I had the test.” I remembered the genetic counselor asking, “Are you Jewish?” and shaking my head. “I want the Tay-Sachs test anyway,” I’d said. Or had I? Had I, in this moment, instantly generated a memory to try to mitigate the present horror?

“I don’t know,” the doctor said uncertainly, and looked as if he might cry. I stared at him. “Did I?” I asked in a squeaky voice, but of course he would not know. He was the eye doctor, a man we’d just met, not the person who had administered the test. He shook his head and cleared his throat. I would later learn that the standard prenatal screening for Tay-Sachs only detects the nine most common mutations—those found among the Ashkenazi Jewish population—but there are more than one hundred known mutations. I would have needed to ask for a combination DNA and enzyme test or requested that my DNA be sequenced. I had not known to ask for either of these. I was told the odds of my being a carrier were “astronomical,” and both parents must be carriers for a child to inherit Tay-Sachs. Rick is Jewish, but by testing one of us, we thought we were covering our bases.

“My mom, my mom,” I said to Rick, gripping his arm and then taking Ronan from him. I clutched at my son, running my shaking hands over his head, his arms, his fat legs. “Little guy, little guy,” I said. He squirmed and giggled. I had the urge to swallow him, to try to return him to my body, where he’d be safe, but of course he’d never been safe, not even there. “Where’s my mom?” I was shouting now. “I need to call my mom. Where’s the phone? Give me the phone.”

“Well, what can we do about it?” Rick asked, glancing between me and Ronan and the doctor, digging in the diaper bag for the cell phone, but I knew enough about Tay-Sachs to know that there was nothing at all for us to do and that my life, the life as a new and hopeful mother, was over.

The doctor looked at the two of us. “No, I’m so sorry,” he said. “There’s no way to fix it.”

“They die,” I stuttered. I had the sensation of skin falling away from bone. I hugged Ronan more tightly. “They. Die.” I wanted to vomit, and my grip on Ronan was scaring him. I loosened my arms slightly.

“What?” Rick asked. “Surely—”

“They die,” I said firmly in a high-pitched voice, and this time he understood that I meant Ronan, that Ronan—our boy, our baby, our child—would die. The world was broken, and the three of us—Ronan, Rick and I—were falling into its mouth

Nerve damage begins in the womb and progresses quickly, leading to dementia, decreased interaction with the environment, seizures, spasticity, and eventually

death. Paralysis, blindness, deafness, loss of all faculties.

The doctor showed us a laminated medical photograph of normal retinas, and then another set with red spots drawn in the center of diseased retinas, ruined eyes. Another doctor checked Ronan’s eyes again, stoically, to confirm the diagnosis. “Yes, I’d agree that it’s Tay-Sachs,” he said, and quickly left the room.

Hearing these details of Ronan’s prognosis, I suddenly, weirdly, remembered meeting a boy called Ronan at Trinity College on a warm, rainy day in Dublin in 1994 and deciding on that name for my future child. I remembered his hand, soft and warm, in my own, and the blond curls that stopped just short of his eyebrows. For years I wrote “Ronan” in longhand scrawls across notebooks like a lovesick teenager, copying over and over again the name, tracing the curved letters as if I were fingering a magic stone. And as if the ghost of Emily Dickinson were speaking directly into my ear, I remembered these lines:

I felt a Cleaving in my Mind / As if my Brain had split

. /

I tried to match it—Seam by Seam— /

But could not make it fit.

The situation didn’t fit; it wasn’t right. My brain was broken; my heart had stopped. How could I still be alive, in this room, having been given this knowledge? It was grotesque and absurd and could not be happening.

When our son’s diagnosis—his death sentence, really—was delivered, I felt all of the known world unraveling, everything splitting apart. The walls of the doctor’s office were no longer beige but purple, glittering, melting, closing in. The nurses were like phantoms, moving in and out of the room with paper cups of water and pinkish-white sedatives balanced like little rafts in their palms, promising relief and oblivion, trying not to stare but staring, whispering

Take this. It will help you relax and calm down

. My voice: not mine. The chairs were a dazzling, terrifying blue and had moved across the room. I was standing on my heart, which was simultaneously beating in my nose. I had finally reached my mother on the phone and was screaming at her but no words left my mouth. My hair was on fire but my face was cold. I had swallowed my own teeth.

What do you mean there’s nothing to do? Are you sure? I can’t believe there’s nothing we can do,

Rick was saying. Action was required, it seemed, but action was useless.

Yet in my blown-apart mind I was already brokering a deal.

If you take Tay-Sachs from Ronan, I will do anything you ask. I’ll stick a knife in anyone’s heart, kill any person, just say the word.

Jesus, Zeus, God, G-d, Allah, anyone. Useless bargaining with a higher power I had long ago stopped believing in. To my own horror, I prayed as I had as a child in church, as I had as a young theologian in divinity school, and I was so overwhelmed, so out of my body, so fully in the dream of disbelief, that I actually believed for a moment that it might work.

“Whatever we can do,” the doctor said in a barely controlled voice. “You just let us know.” But what could he—or we—do? There was nothing to do. He filled our heads with more information—names of doctors, specialists, geneticists—while Rick and I sat on uncomfortable chairs and clung to each other in the overheated, badly lit room, repeating each other’s first names.

Finally, with Ronan carried between us in his car seat, we stumbled out of the examination room as if groping our way through a dark tunnel instead of the well-lit hallway.

“Why is the floor wet?” I asked Rick. Ronan gurgled and burped in his car seat.

“It isn’t,” he said. “It’s carpeted. This is carpet.”

“Be careful,” I insisted. “Don’t slip. Don’t drop the baby!”

“I’ve got him. I’m fine. It’s fine.”

“Take care,” the nurses said with trembling voices as we passed their station.

Riding home in the backseat, clutching at my kid, who sat giggling in his car seat, oblivious to his wretched future, I thought

I can’t believe I’m awake for this. I don’t want to be awake for this.

I was filled with a pulse-pounding terror, a wrenching euphoria of disbelief. My chest was hot, liquid and loud with fear. I felt gleaming and flattened.

I’m sure I had the test for Tay-Sachs,

I reminded myself.

It’s a mistake; it must be.

The cars on the highway looked as real to me as those on

The Jetsons

. My parents were already on their way from Cheyenne, Wyoming, to Santa Fe, a seven-hour drive, and I called them nearly every ten minutes until they arrived, when I stumbled, wailing, into my mother’s arms, sedated but still writhing, out of time and feverish with panic and fear. I repeated “blackness,” over and over again, and I could feel it descending. I put my hands over my head as if to shield myself. I called my closest friends and screamed and wept into the phone.

I’m here,

they promised.

I’ll leave the phone on, I’ll book a ticket, tell me what I can do.

I couldn’t eat or think, and when I moved, I paced back and forth in my room. I threw a chair at the wall and kicked it with my bare foot. I knelt on the floor and hit my head against the wood until Rick pulled me up, and then I hit my head against the wall. Rick and I met with Matt, the chairman of my department at the arts school where I teach writing and literature, but I remember very little about the conversation, only that as I watched Rick explain to him why I wouldn’t be able to teach for the next few weeks, and struggling not to cry, I was thinking of friends who had lost parents and children, and I kept asking Rick, again, if I could use his phone.

I have to call them,

I pleaded, clawing at his jacket.

And tell them that I know their hearts, that I know them now.

And then, finally, I slept.

• • •

As news of Ronan’s diagnosis spread, our house on Sol y Luz Street, “street of sun and light,” in Santa Fe became a busy place, its own little planet. Baskets of food arrived at our door. Phone calls poured in. My friend Emily booked a ticket from London to arrive in a matter of days. A constant flurry of e-mails began, which I checked compulsively, as if sending e-mails like a normal, functional person would save me from facing reality. I nibbled at some Danish that my friends Lisa and David had sent from Los Angeles. My friend Tara called me every hour from Phoenix.

I took Ronan for a walk in his front carrier pack, crying behind a pair of diva sunglasses. I stopped wailing, except at night, when I would cry myself into a pit and then sleep there, shallowly. When I woke up, I felt as if I’d spent the night in a cold, skinny ditch by the side of some lonely road. Every morning the sky was bright blue and mocking, the trees along the walking trail outside our house still bare, everything brown. The world blue-brown but black, like a bruise. We felt beat up, pressed down. The world had a wild, new, terrifying clarity. I thought of these lines from “The Elm,” by Sylvia Plath:

Now I break up in pieces that fly about like clubs / A wind of such violence /

Will tolerate no bystanding: I must shriek.

They repeated over and over again in my head like a ticker tape, like a mantra, like a warning from a future haunted version of myself.

In Boston my friend Weber went online and found the National Tay-Sachs and Allied Diseases Association and joined on our family’s behalf. Mothers of children who had died of Tay-Sachs started calling me from phone numbers and area codes I didn’t recognize—moms from Florida, New York, New Jersey, California. I talked with them for hours, in my bed and under the covers with Ronan, sweating, clinging to my son. I learned details of what his care would entail: head supports, bath chairs, seizure medications, suction machines. I clung to one mom’s description that Tay-Sachs would function like a “slow fade” and that Ronan would not be in pain. It felt strange to be sharing, suddenly, such a life-altering experience—the very worst experience—with people I hardly knew. I appreciated that this dynamic meant that all the usual formalities disappeared. Instead it was

what do you want to know

and

you are not alone

and

yes, there’s hope for future children

and

it is the worst thing you will ever experience and you will survive if not ever fully recover

and

you call me anytime and ask me any question and I will tell you the truth and I am here.

No platitudes (“What doesn’t kill you will make you stronger!”), no annoying, schmaltzy pseudo-Christian phrases like “When God closes a door, he opens a window.”

Weber gently asked if I planned to write about Ronan. “Uh . . . I don’t know . . . maybe.” I stuttered. “I’ll set up a blog space,” she said. “You can always decide later.” I didn’t think much about it at the time. I talked to the other moms with terminally ill babies, I took Xanax, I sobbed and bit my lip, my sheets, my hands. And then I got out of bed, and, to my great surprise, I started to write.