The Story of Rome (30 page)

From the Forum, three narrow streets led up to the Byrsa or Castle of Carthage. The houses on either side of these streets were six storeys high, and to these the inhabitants of the city rushed.

As the Romans pushed their way along the narrow streets, the Carthaginians flung down upon them from windows and roofs every missile or weapon on which they could lay their hands.

At length Scipio ordered his men to storm the houses. Then a terrible hand-to-hand fight began with the starving citizens.

Clambering on to the roofs, which were flat, the soldiers stretched boards or beams across from one house to another, and hurled out of the way those citizens who still tried to hinder their progress.

For six days and nights the desperate townsfolk continued to baffle the efforts of the Romans to reach their last stronghold, the Byrsa.

During this awful struggle, Scipio himself sent forward continually new companies of men, and in his anxiety he scarcely found time to sleep or to eat.

At length, however, the foot of the citadel was reached, and Scipio ordered the narrow streets to be set on fire.

Then the Carthaginians knew that they could do no more, and those who had taken refuge in the Byrsa surrendered, on being promised that their lives should be safe.

Fifty thousand men, women, and children, pale and haggard with all that they had gone through during the long drawn out siege, left the castle and were carried off as prisoners.

Hasdrubal, who had defended the city so bravely, was still untaken. He, with his wife and children, as well as about nine hundred Romans who had deserted their own camp, now took refuge in the temple of Æsculapius, and set fire to it themselves.

But Hasdrubal, feeling, it may be, that he could not help his country by his death, resolved to save his life.

He escaped from the burning temple, and, with an olive branch in his hand, threw himself at the feet of Scipio, begging for life. And the Roman commander granted his request.

It is told that the wife of Hasdrubal stood on the roof of the temple and cursed her husband as she saw him crouching at the feet of the conqueror.

Calling aloud to him that he was a traitor and a coward, she flung first her two sons and then herself into the flames before the eyes of her horror-stricken husband.

Meanwhile, with all speed a ship was sent to Rome, laden with the spoils of Carthage.

Great was the rejoicing in the city when it was known that her ancient rival was in ruins. Orders were at once sent to Scipio, bidding him complete his work by destroying the town.

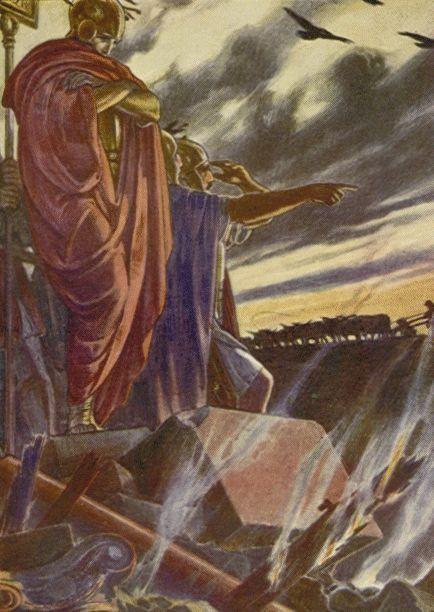

So Carthage was given to the flames, and for seventeen days the fire blazed untiringly. Scipio, as he watched the doomed city, thought of other great countries that had been destroyed by their enemies—Assyria, Persia, Macedonia. In the unknown future would Rome fall even as these?

The city was given to the flames.

Thinking thus, Scipio murmured the lines of Homer:

"The day shall come when holy Troy shall fall,

And Priam, lord of spears and Priam's folk."

When the flames had at last died out, a plough, drawn by oxen, was driven over the site of the town, and Scipio uttered a solemn curse against any one who should venture to build a new city on the ancient site of Carthage.

CHAPTER LXXIX

Cornelia, the Mother of the Gracchi

C

ORNELIA

and her two sons, Tiberius and Gaius, are famous in the annals of Roman history.

The mother of the Gracchi was the daughter of the first Scipio Africanus. With her father's consent, Cornelia married a young plebeian, named Tiberius Gracchus.

Her husband died while her children were still young, and from that time Cornelia lived to train and educate her boys.

Princes in foreign countries heard of the wisdom and goodness of the noble matron, and journeyed to Rome to beseech her to bestow her hand upon them. Even King Ptolemy of Egypt wished to make her his queen.

But Cornelia steadfastly refused each suitor, that she might be free to watch over her sons. From their childhood she taught them to love their country, telling them tales of those who had served Rome well, and had even given their lives for love of her.

And so the lads grew up longing that they too, like the heroes of old, might live and die for their country. But their mother taught them lessons the heroes of old had never learned, and one of these lessons was to care for the poor and oppressed.

One day, while her children were still young, a lady came to visit Cornelia. She was a rich lady, and proud of her jewels and her wealth.

Cornelia listened quietly as her guest told her of the precious stones and ornaments she possessed. When at length she grew tired of talking of her own beautiful things, she said she would like to see the treasures of her hostess.

So Cornelia led the lady to another room. There, in bed, fast asleep, lay her children. Pointing to the little ones, she said to the bewildered visitor, "These are my jewels; the only ones of which I am proud."

Tiberius was nine years older than his brother Gaius. The elder boy was gentle and deliberate, both in his ways and in his speech, the younger was vehement and impetuous. As they grew up, the differences between them grew more marked.

Both were great orators, but Tiberius spoke without gestures, and seldom stirred from one spot while he addressed his audience.

Gaius, on the other hand, was never still for a moment. His quick, passionate words were emphasised by his gestures, and as he talked he would walk up and down, sometimes in his excitement throwing his gown off his shoulders.

The two brothers were known as "The Gracchi." They had a sister who was named Sempronia, and she had married the younger Scipio. Tiberius served under his brother-in-law in Africa, and he was the first to mount the wall when the suburb of Megara was attacked.

In 137

B

.

C

.

, soon after he returned to Italy, he was sent to Spain to serve with the army there.

On his way he passed through Etruria, where the land was divided into large estates. These estates belonged to rich people, who employed gangs of slaves to cultivate their fields.

Tiberius saw the slaves at work as he journeyed through the country. He noticed that they were loaded with chains and bent with the hard tasks that their masters forced them to do.

The young man looked at these poor creatures with pity, for Cornelia had taught her boys that slaves were human beings, and should be treated justly and kindly.

Why should the land belong only to the rich? Tiberius wondered. Had these very fields and estates not been won for Rome by her citizen soldiers? Yet many of the soldiers were now struggling with poverty, instead of owning part of the soil for which they had fought.

As he thought of the slaves, and of the unfair division of land, Tiberius remembered that the old Licinian laws forbade any one man to own large tracts of land.

So he determined that when he went back to Rome he would plead with the Senate to enforce these old laws, that the poor might share the land with the rich.

After he had made this resolution, Gracchus went on his way with happy thoughts.

Soon no chained slaves would be seen toiling in the fields, but citizen farmers, like Cincinnatus of old, would live on their own land and till their own fields. And he, Tiberius Gracchus, would have freed his country from a great evil.

The dreams of the young Roman that night were happy dreams.

When the time came for Tiberius to return to Rome, his mind was still full of reform. No sooner did he reach home, than he told to his noble mother his plans for helping the slaves and the poorer citizens of Rome, and begged for her advice.

Cornelia was full of interest in all that her son had to tell. She was pleased that he should wish to help the oppressed, and she knew that it was she herself who had taught him to be thus pitiful.

"I have been called the daughter of Scipio, but in days to come I shall be known as the mother of the Gracchi," she told Tiberius, for Cornelia believed that both her boys would be honoured by the country they sought to serve.

So in 133

B

.

C

.

Tiberius offered himself as one of the people's tribunes. He was young, it was true, but already the citizens knew that he was their friend, and he was elected without difficulty.

CHAPTER LXXX

Tiberius and His Friend Octavius

T

HE

Senate and the wealthy landowners were displeased that Gracchus had been chosen as one of the tribunes. They knew that he was eager for reforms, which they had no wish to see carried out.

But Tiberius was too wise not to try to please those in authority. So his first measure was not so sweeping as his opponents had expected it to be. The young reformer even said, that those who would lose great estates, if the old Licinian laws were enforced, should have compensation.

But although the landowners had not expected this concession, they were very angry with Tiberius, and they did all that they could to make the people misunderstand him. If his wishes were made laws, the lot of the poor would only become more difficult, they told the plebeians, who did not know what to believe.

Then, lest the people should begin to think that the landowners knew better than he what was for their good, about their struggles and their poverty.

In the Assembly of the people his fervent words rang out.

"The wild beasts of Italy," he said, "have their caves and lairs, but to the men who fought and bled for Italy nothing remains except the open air and the light of heaven. Bereft of home and shelter, they wander about with their wives and families. It is a mere mockery and a delusion in a general to exhort his warriors before a battle by bidding them fight for the graves of their ancestors and for their household altars, for not one of them owns an altar bequeathed him by his father, nor the ground where his fathers are laid. They fight and fall that others may enjoy affluence and luxury; they are called lords of the earth, and have not a single clod which is their own."

These words, so full of pity for the treatment that they suffered, touched the hearts of the people, and they would no longer listen to a word against their tribune.

Among his fellow-tribunes, Tiberius scarcely looked for support, save, perhaps, from his friend Octavius.

At first, indeed, Octavius refused to oppose the bill Gracchus now brought forward, but in the end he yielded to the enemies of Gracchus, and promised to do so.

This was fatal to the success of the bill, for it was the rule that if one tribune disapproved of a measure, the others were powerless to do any more in the matter. It was allowed to drop out of sight. Tiberius was too much in earnest to be willing that this should happen. He met his friend and begged him not to persist in opposing the bill.

Octavius himself was a landowner, and Gracchus, careless, as it seemed, of his friend's feelings, even offered to compensate him for what he would lose if the law was passed.

But Octavius was neither to be persuaded nor bribed. He refused to do as Tiberius wished, and so it was still impossible to pass the bill.

Then Tiberius, who as tribune had exactly the same power as his friend, resolved to use it.

He opposed every measure brought before the State, just as Octavius had opposed his bill. He also put his seal on the treasury, so that no money could be obtained, and thus it was soon impossible to carry on public business.

The landowners knew that Tiberius would not rest until he had gained his end. To show their distress they put on mourning, and walked up and down the streets with a melancholy mien, for their estates were dear to them.

But they did more than parade their grief; they called together their followers that they might be ready to resist Gracchus by force, if it became necessary. Plots, too, were laid against his life, but Tiberius heard of these, and from that time he carried a dagger beneath his robe.

The landowners were right in believing that Gracchus would never be content until his bill had been voted either for or against by the people.

Not only did the tribune intend to have the vote taken, but he was resolved that it should be taken without delay. For the people had crowded into the city from all parts of the country to support him, and he feared lest they should have to go back to their homes before their vote had been given.

So he made another attempt to bring his bill before the popular Assembly, but again Octavius interfered, while some haughty nobles led their followers into the Assembly and overturned the urns in which the votes were placed.

Again Gracchus appealed to his friend, this time in the presence of the Senate, but once again his friend refused to yield to his entreaty.