The Story of Rome (38 page)

Now Aristion was a great orator, and he knew that his words would influence the people to do as he wished.

So first he reminded them of all the wrongs that Athens had suffered from the Romans, and if these wrongs were not all real, Aristion made them seem so by his eloquence.

Then he spoke of Mithridates, and of the king he had nothing but good to tell, while the magnificence of his court, Aristion modestly declared, baffled even his powers of description.

Before Aristion had finished his oration, the magistrates of Athens had determined to proclaim their republic restored, and to form an alliance with Mithridates. Aristion was appointed chief minister of war, and you shall hear how sadly he failed to do his duty when trouble befell the city.

Sulla having landed with his army at Epirus, at once marched to Athens, for by this time both the city and the Peiræus were strongly fortified, and held by Archelaus, the general of Mithridates.

The Roman commander determined to besiege the citadel, and to surround Athens with soldiers, to prevent the citizens from escaping, or provisions from being sent to their relief.

As he had neither money nor material for the siege, Sulla robbed the temples of Greece of their treasures.

Timber was brought from far and near in carts drawn by mules, ten thousand, it is said, in number. When even this was found not to be enough, Sulla ordered the sacred groves to be cut down, as well as the trees which surrounded the famous academy of Athens.

But, in spite of the forts he built and the trenches he dug, Sulla could not take the Peiræus.

As they worked, the Roman soldiers were often interrupted by Archelaus, who with his troops would sally out of the citadel to attack them.

At length Sulla was convinced that without a fleet he need not hope to take the citadel, for the harbour was commanded by the ships of Mithridates.

CHAPTER XCVII

Sulla Besieges Athens

T

HE

Peiræus could not, indeed, be starved into submission as long as the king held the harbour, but Athens was already suffering from famine.

Now the Athenians were a gay and careless people, little accustomed to endure hardships, yet no one grumbled at the lack of food, but each bore his hunger manfully, or tried to stay its pangs as best he could.

Some fed on herbs, which they gathered painfully, for they had grown feeble with long fasting. Others hunted for old leather shoes or pieces of oilskin, and when they found them, soaked them in oil, and so made a sorry meal.

But while the inhabitants of Athens starved, Aristion, the orator and minister of war, who was largely responsible for the misery of the people, lived at his ease, and ate and drank as much as he pleased. Nor did he feast in secret, but before the eyes of the famished folk, for he was as careless of their sufferings as of his own responsibilities.

At length the senators and priests went to the tyrant, for such had Aristion proved, and begged him to make terms with Sulla before the citizens died of hunger. But Aristion did not wish his pleasures interrupted by such solemn messengers. He drove them from his presence, bidding his servants to send a flight of arrows after the procession as it turned sadly away.

A little later, however, he appeared to yield to the wishes of the senators, and sent two or three of his gay companions to meet the Roman general.

But they had no serious terms to propose, and were not commissioned to accept any. All they seemed able to do, was to talk eloquently about their ancient towns and games, until at length Sulla grew impatient and said: "My good friends . . . begone. I was sent by the Romans to Athens, not to take lessons, but to reduce rebels to obedience."

Soon after this, Sulla, by chance, found out how the city might be taken.

Two old men were talking to each other of Aristion's follies, and Sulla overheard them blame him for leaving a certain weak part of the city walls unguarded.

The Romans at once set to work to find out the weak spot in the defences, and when it was found an attack was made at that point.

Only a few sentinels were on duty, and they fled at the approach of the enemy, so a breach was soon made, through which Sulla marched into the city at the head of his troops.

In their triumph at having taken the city the soldiers ran wild, plundering and slaying the wretched inhabitants, many of whom killed themselves rather than fall into the hands of their cruel conquerors.

Sulla looked on, heedless of the fate of the citizens, careless, too, of the destruction of the beautiful city. Only when two citizens, who had refused to give up their friendship with Rome, flung themselves at his feet and begged him to spare the city for the sake of her ancient renown and her famous Athenians, did he yield.

Even then it was with ungracious voice and sullen face that he bade his soldiers desist from further plunder. Then, turning to those who had pleaded with him to save the city, he said: "I forgive the many for the sake of the few, the living for the dead."

Soon after this the Peiræus also fell, and Sulla ordered it to be destroyed, and the docks and magazines to be burnt.

In the same year as Athens and the Peiræus fell, Sulla met the troops of Mithridates at Chæronea, where a great battle was fought. Archelaus was defeated, although he had nearly four times as large a force as Sulla.

Greece now began to repent of her folly in having rebelled against Rome. Mithridates seemed unable to help them as much as Aristion and their own hopes had led them to expect. So, many of the Greek cities in Asia Minor left the king and submitted to the Romans.

But Mithridates determined to make one more great effort to regain his power. He met the Romans at Orchomenus, and here another great battle was fought in the autumn of 86

B

.

C

.

At first the Romans began to give way before the fierce attack of the king's troops. But Sulla saw the danger, and leaping from his horse he seized a standard and rushed into the thick of the fight, shouting: "To me, O Romans, it will be glorious to fall here. As for you, when they ask you where you betrayed your general, remember to say at Orchomenus."

Stung by their general's words his men rallied, and after a desperate struggle the battle was won, and the power of Mithridates broken.

In 84

B

.

C

.

the king was forced to make terms with the Romans, while those cities which had fought by his side had to pay enormous sums of money to Sulla.

The victorious general was now anxious to go back to Rome, to punish those who had declared him a public enemy. So, in the spring of 83

B

.

C

.

, he set out for Italy with his army.

CHAPTER XCVIII

Sulla Saves Rome from the Samnites

S

ULLA

returned to Italy three years after the death of Marius. During that time the popular party had been in power. But now it feared that its reign was nearly at an end, for Sulla was in Italy, and was coming to Rome, and coming not alone, but with his army.

Carbo was the leader of Sulla's enemies. He had gathered together a large army, but it was scattered over Italy, under his lieutenants. Pompey, who was soon to be known as Pompey the Great, was fighting for Sulla, and he, with three legions, kept Carbo's forces from uniting. This made Sulla's victory the easier.

But while Romans fought with Romans, a new danger threatened the city. An army of Samnites, under a leader named Pontius, slipped past both the army of Sulla and the scattered troops of Carbo, and marched straight toward Rome.

The citizens were in despair. They remembered the Samnites who long ago had entrapped their army at the pass of the Caudine Forks, and their leader Pontius, who had made Roman officers and soldiers pass beneath the yoke, and they trembled. What if the enemy proved as powerful as of old?

Private quarrels were forgotten, while all those of military age in the city armed for her defence.

In their walls the people had no confidence, for here and there they were broken down and unfit to stand a siege.

So out of the city to meet the terrible foe marched the valiant band of Romans, only to find the enemy too strong for it.

When it was known in the city that the army so hastily enrolled had been defeated, the despair was profound. Women ran about the streets crying aloud to their gods and shrieking in terror. At any moment, they believed, the Samnites might enter their city.

Then, just when hope of relief was faintest, a large company of cavalry was seen approaching the gates. It was the vanguard of Sulla's army, and he himself was close behind with the main body of his troops.

For the time a feeling of immense relief was felt in the city. At least the Samnites would not enter Rome now unopposed.

Sulla's officers begged him to allow his troops to rest before attacking the enemy. But he refused, ordering the trumpets at once to sound for battle.

Crassus commanded Sulla's right wing, and, unknown to the general, beat the enemy. The left wing of the Romans was all but repulsed, when Sulla rode to its help, mounted on a swift white steed.

He was recognised by the Samnites, and two of them prepared to fling their darts at the great Roman general. They thought that if he were slain the battle would soon be at an end.

But Sulla's servant saw his master's danger, and gave his steed a touch that made him start suddenly forward. The darts fell harmless to the ground close to the horse's tail, so that the servant had just succeeded in saving his master's life.

Darkness fell, and the battle was still undecided. But during the night messengers from Crassus stole into Sulla's camp for provisions, and the general heard that the enemy had been driven to Antemnæ, three miles away, and that Pontius, the Samnite leader, had been slain. He at once resolved to join Crassus. In the morning the Samnites were surprised to find a large army ready to attack them. But their leader was dead, so they were afraid to fight, and three thousand offered to submit to Sulla.

The general promised these their lives on one condition—that they should attack their own comrades. This the Samnites actually agreed to do, and a large number were killed in the unnatural struggle.

Six thousand who survived were taken to Rome, and by Sulla's orders cut to pieces. The cruelty of the Roman commander seemed to increase the nearer he drew to Rome.

CHAPTER XCIX

The Proscriptions of Sulla

A

FTER

his victory over the Samnites, Sulla met the Senate in the temple of Bellona, without the walls of the city.

Ominous thoughts stole into the minds of the senators and distracted them, as the general's speech was suddenly interrupted by terrible shrieks as of those in agony.

Sulla alone remained undisturbed. But seeing that the senators were not listening to his speech, he sternly bade them "not to busy themselves with what was doing out of doors."

The cries were those of the six thousand Samnite prisoners, who were being ruthlessly slain by Sulla's orders.

At this time, too, young Marius, who had fought against Sulla, killed himself rather than fall into the hands of his father's enemy.

His head was brought to Sulla at Rome. "One should be rower before one takes the helm," said the tyrant, looking with unconcern at the hideous trophy. For he was angry that young Marius had been chosen Consul when he was only twenty-seven years of age.

The forebodings of many were now justified, for Rome became as a city of the dead. Sulla had determined to kill all who had been his enemies while he was absent in Greece.

Day after day the cruel slaughter went on. Forty senators and sixteen hundred of the citizens were condemned, and to add to the consternation among those who had escaped, there were others yet to be punished. Sulla said that he could not remember their names. The suspense in the city was terrible.

One senator, bolder than the others, said to Sulla: "We do not ask you to pardon any whom you have resolved to destroy, but to free from doubt those whom you are pleased to spare."

"I know not as yet whom I will spare," grimly answered the general.

"Why, then," persisted the senator, "tell us whom you will punish."

Sulla promised to do this, and henceforth lists of those who were doomed were hung up in the Forum. These lists were called the "Proscriptions of Sulla."

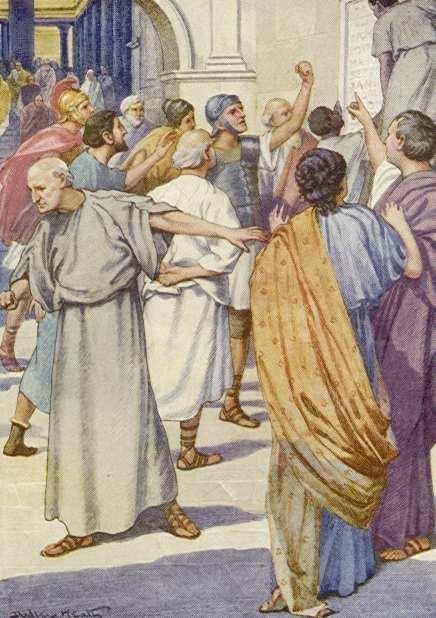

Lists of those who were doomed were hung up in the Forum.

In the first list eighty persons were proscribed, and for a moment Rome dreamed that there would be no more dread uncertainty, that the end of the death sentences had at least come in sight.

But the horror in the city was but heightened by the proscriptions, when the first list was followed by another, and yet another.

Moreover, an edict was published, saying that if any one dared to give shelter or food to a proscribed person he would be punished with death. While, if any one killed a person whose name was on the list of the condemned, he would be rewarded. The property of those who perished was forfeited, and in this way Sulla and his friends soon grew rich. These cruel proscriptions remain for ever a blot on Sulla's fame.