The Story of the Romans (Yesterday's Classics) (23 page)

Because they were honest, these men first of all told Nero that he had better send his mother away from court, where her influence could do no good. Nero followed this advice, and during the first months of his reign he was generous, clement, and humane. We are told that when he was first asked to sign the death warrant of a criminal, he did so regretfully, and exclaimed: "Oh! I wish I did not know how to write!"

Nero was only about seventeen years of age when he began his reign. He was handsome, well educated, and pleasant-mannered, but unfortunately he, too, was a hypocrite. Although he pretended to admire all that was good, he was in reality very wicked.

His mother, Agrippina, had set him on the throne only that she herself might reign; and she was very angry at being sent away from court. However, she did not give up all hopes of ruling, but made several attempts to win her son's confidence once more, and to get back her place at court. Seeing that coaxing had no effect, she soon tried bolder means. One day she entered the hall where Nero was talking with some ambassadors, and tried to take a place by his side.

Nero saw her come in, and guessed what she intended to do. He rushed forward with exaggerated politeness, took her gently by the hand, and solemnly led her,—not to a seat of honor by his side, but to a quiet corner, where she could see all, but where she would hardly be seen.

Agrippina was so angry at being thus set aside that she began to plan to dethrone Nero and give the crown to Britannicus instead. This plot, however, was revealed to the young emperor. As soon as he heard it, he sent for Locusta, and made her prepare a deadly poison, which he tested upon animals to make sure of its effect.

When quite satisfied that the poison would kill any one who took it, Nero invited his stepbrother to his own table, and cleverly poisoned him. Although Britannicus died there, before his eyes, the emperor showed no emotion whatever; but later on he saw that the people mourned the young victim, and then he pretended to weep, too.

His wife, Octavia, the gentle sister of Britannicus, was sent away soon after, and in her place Nero chose Poppæa, a woman who was as wicked as Messalina or Agrippina. This woman gave him nothing but bad advice, which he was now only too glad to follow.

Having killed his brother, Nero next began to plan how he might kill his mother. He did not wish to poison Agrippina, so he had a galley built in such a way that it could suddenly be made to fall apart.

As soon as this ship was ready, he asked his mother to come and visit him. Then, after treating her with pretended affection, he sent her home on the treacherous galley. As soon as it was far enough from the shore, the bolts were loosened, and the ship parted, hurling Agrippina and her attendants into the sea.

One of the queen's women swam ashore, and cried out that she was Agrippina, in order to secure prompt aid from some men who stood there. Instead of helping her, the men thrust her back into the water, and held her under until she was drowned; for they had been sent there by Nero to make sure that no one escaped.

The real Agrippina, seeing this, pretended to be only a waiting maid, and came ashore safely. The young emperor was at table when the news of his mother's escape was brought to him. He flew into a passion on hearing that his plans had failed, and at once sent a slave to finish the work that had been begun.

In obedience to this cruel order, the slave forced his way into Agrippina's room. When she saw him coming with drawn sword, she bared her breast and cried: "Strike here where Nero's head once rested!" The slave obeyed, and Nero was soon told that his mother was dead.

The Christians Persecuted

A

T

first, Nero was rather frightened at his own crimes. The Romans, however, did not resent the murder of Agrippina, but gave public thanks because the emperor's life had been spared; and when Nero heard of this he was quite reassured. Shortly afterwards, the gentle Octavia died too, and then Nero launched forth into a career of extravagance as wild as that of Caligula.

Always fond of gladiatorial combats and games of all kinds, Nero himself took part in the public chariot races. Then, too, although he had a very poor voice, he liked to go on the stage and perform and sing before his courtiers, who told him that he was a great actor and a very fine singer.

Encouraged by these flatterers, Nero grew more conceited and more wild. To win his favor, many great people followed his example; and noble ladies soon appeared on the stage, where they sought the applause of the worst class in Rome.

The poor people were admitted free of charge at these games, provided that they loudly applauded Nero and his favorites. As they could not attend to their work, owing to the many festivities, the emperor ordered that they should be fed at the expense of the state; and he made lavish gifts of grain.

A comet having appeared at this time, some of the superstitious Romans ventured to suggest that it was a sign of a new reign. These words were repeated to Nero, and displeased him greatly; so he ordered that all the people who spoke of it should be put to death, and that their property should be confiscated for his use.

Some of these unfortunate Romans took their own lives in order to escape the tortures which awaited them. There were others whom the emperor did not dare to arrest openly, lest the people should rise up against him; and these received secret orders to open their veins in a bath of hot water, and thus bleed to death.

For the sake of the excitement, Nero used to put on a disguise and go out on the highways to rob and murder travelers. On one occasion he attacked a senator, who, failing to recognize him, struck him a hard blow. The very next day the senator found out who the robber was, and, hoping to disarm Nero's rage, went up to the palace and humbly begged his pardon for striking him.

Nero listened to the apologies in haughty silence, and then exclaimed; "What, wretch, you have struck Nero, and are still alive?" And, although he did not kill the senator then and there, he nevertheless gave the man strict orders to kill himself; and the poor senator did not dare to disobey.

Nero had received a very good education, and so he was familiar with the great poem of Homer which tells about the war of Troy. He wished to enjoy the sight of a fire, such as Homer describes when the Greeks became masters of that city. He therefore, it is said, gave orders that Rome should be set afire, and sat up on his palace tower, watching the destruction, and singing the verses about the fall of Troy, while he accompanied himself on his lyre.

A great part of the city was thus destroyed, many lives were lost, and countless people were made poor; but the sufferings of others did not trouble the monster Nero, who delighted in seeing misery of every kind.

Ever since the crucifixion of our Lord, during the reign of Tiberius, the apostles had been busy preaching the gospel. Peter and Paul had even visited Rome, and talked to so many people that there were by this time a large number of Roman Christians.

The Christians, who had been taught to love one another, and to be good, could not of course approve of the wicked Nero's conduct. They boldly reproved him for his vices, and Nero soon took his revenge by accusing them of having set fire to Rome, and by having them seized and tortured in many ways.

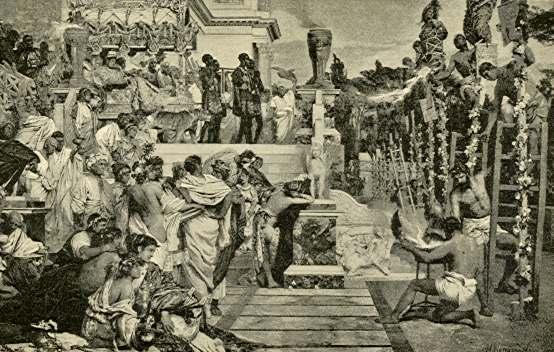

Some of the Christians were beheaded, some were exposed to the wild beasts of the circus, and some were wrapped up in materials which would easily catch fire, set upon poles, and used as living torches for the emperor's games. Others were plunged in kettles of boiling oil or water, or hunted like wild beasts.

Nero's Torches

All of them, however, died with great courage, boldly confessing their faith in Christ; and because they suffered death for their religion, they have ever since been known as Martyrs. During this first Roman persecution, St. Paul was beheaded, and St. Peter was crucified. St. Peter was placed on the cross head downward, at his own request, because he did not consider himself worthy to die as his beloved Master had died.

Nero's Cruelty

A

S

Rome had been partly destroyed, Nero now began to rebuild it with great magnificence. He also built a palace for his own use, which was known as the Golden Palace, because it glittered without and within with this precious metal.

Nero was guilty of many follies, such as worshiping a favorite monkey, fishing with a golden net, and spending large sums in gifts to undeserving courtiers; and he is said never to have worn the same garment twice.

Of course so cruel and capricious a ruler as Nero could not be loved, and you will not be surprised to hear that many Romans found his rule unbearable, and formed a conspiracy to kill him. A woman named Epicharis took part in the plot; but one of the men whom she asked to help her proved to be a traitor.

Instead of keeping the secret, this man hastened to Nero and told him that Epicharis knew the names of all the conspirators. So the emperor had her seized and cruelly tortured, but she refused to speak a word, although she suffered untold agonies. Then, fearing that she would betray her friends when too long suffering had exhausted her courage, Epicharis strangled herself with her own girdle.

As Nero could not discover the names of the conspirators, he condemned all the Romans whom he suspected of having been in the secret, and forced them to kill themselves. Even his tutor Seneca obeyed when ordered to open his veins in a warm bath; and he died while dictating some of his thoughts to his secretary.

The poet Lucan died in the same way, and as long as his strength lasted he recited some of his own fine poetry. We are told that the wife of one victim of Nero's anger tried to die with her husband, but that Nero forbade her doing so, had her wounds bound up, and forced her to live.

Nero was so brutal that he killed his own wife Poppæa by kicking her, and so inconsistent that he had her buried with great pomp, built temples in her honor, and forced the Romans to worship her.

As Nero's crimes were daily increasing in number, a new conspiracy was soon formed against him. This time, his soldiers revolted. The legions in Spain elected their general, Galba, as emperor, and marched toward Rome to rid the world of the tyrant Nero.

The emperor was feasting when the news of Galba's approach reached him. He was so frightened that he fled in haste, carrying with him a little box which contained some of Locusta's poisonous drugs. He rushed from door to door, seeking an asylum, which was everywhere denied him; but finally one of his freedmen led him to a miserable little hut, where he was soon followed by his pursuers.

When Nero heard his enemies coming, he realized that he could not escape death, and sadly exclaimed: "What a pity that such a fine musician should perish!" Then he made a vain attempt to cut his own throat, and, had not his freedman helped him, he would have fallen alive into Galba's hands.

Nero was only a little over thirty when he died; and he had reigned about fourteen years. He was the last Roman emperor who was related to Augustus, the wise ruler who had done so much to further the prosperity of Rome.

Two Short Reigns

G

ALBA

,

the new emperor, was more than seventy years old at the time of his election; and he soon discovered that he could not do all that he wished. He tried very hard to curb the insolence of the soldiers, to punish vice, and to fill the empty state treasury; but he was not able to accomplish any of these ends.

He had several favorites, and according to their advice he was either too severe or too lenient. His lack of firmness soon gave rise to discontent and revolts. As he had no son to succeed him, Galba wished to adopt a fine young man named Piso Licinianus, but the senate and soldiers did not approve of this choice.

Otho, a favorite of Galba, had hoped to be adopted as heir; but when he saw that another would be selected, he bribed the soldiers to uphold him, with money which he stole from Galba's treasury. The mob believed all that Otho told them, and declared that he should be emperor in Galba's stead.

Rushing off to the Forum, they met the emperor, and struck off his head. This was then placed on a lance, and carried around the camp in triumph, while the deserted body was carried away and buried by a faithful slave.

After a very brief reign, Otho heard that the Roman legions on the Rhine had elected their commander Vitellius as emperor, and were coming to attack him. He bravely hastened northward to meet them, and in the first encounters his army had the advantage.

In the great battle at Bedriacum, however, his troops were completely defeated, and two days later Otho killed himself to avoid falling into the enemy's hands. Soon Vitellius entered Rome as emperor, and as the successor of Galba and Otho, whose combined reigns had not lasted even one year.

The Siege of Jerusalem

T

HE

new emperor, Vitellius, was not cruel like Tiberius, Caligula, and Nero, nor imbecile like Claudius, nor a victim of his favorites like Galba; but he had a fault that was as disastrous as any. This was gluttony. He is said to have been so greedy that even now, over eighteen hundred years after he died, his name is still used as a byword.