The Story of the Romans (Yesterday's Classics) (5 page)

When Tullus Hostilius heard this pitiful request, he promised to forgive Horatius upon condition that he would lead the Roman army to Alba, and raze the walls of that ancient city, as had been agreed. The Albans were then brought to Rome, and settled at the foot of the Cælian hill, one of the seven heights of the city.

By other conquests, Tullus increased the number of his people still more. But as the streets were not yet paved, and there were no drains, the town soon became very unhealthful. A plague broke out among the people, many sickened and died, and among them perished Tullus Hostilius.

Tarquin and the Eagle

A

S

Tullus Hostilius was dead, the Romans wished to elect a new king; and they soon chose Ancus Martius, a grandson of the good and pious Numa Pompilius who had governed them so well. The new ruler was very wise and good. Although he could not keep peace with all his neighbors, as his grandfather had done, he never went to war except when compelled to do so.

There were now so many people in Rome that it was not easy to govern them as before. In fact, there were so many wrongdoers that Ancus was soon forced to build a prison, in which the criminals could be put while awaiting judgment. The prison was made as solid as possible, with thick stone walls. It was so strong that it still exists, and one can even now visit the deep and dark dungeons where the prisoners used to be kept more than six hundred years before Christ.

During the reign of Ancus Martius, as in those of the kings before him, many strangers came to settle in Rome. They were attracted thither by the rapid growth of the city, by the freedom which the citizens enjoyed, and by the chances offered to grow rich and powerful.

Among these strangers was a very wealthy Greek, who had lived for some time in a neighboring town called Tarquinii. This man is known in history as Tarquinius Priscus, or simply Tarquin, a name given him to remind people where he had lived before he came to Rome.

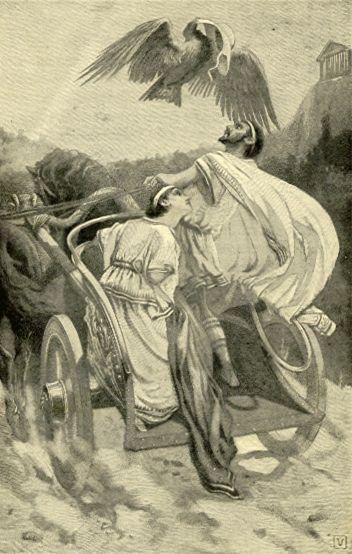

As Tarquin was rich, he did not come to Rome on foot, but rode in a chariot with his wife Tanaquil. As they were driving along, an eagle came into view, and, after circling for a while above them, suddenly swooped down and snatched Tarquin's cap off his head. A moment later it flew down again, and replaced the cap on Tarquin's head, without doing him any harm.

Tarquin and the Eagle

This was a very strange thing for an eagle to do, as you can see, and Tarquin wondered what it could mean. After thinking the matter over for a while, he asked his wife, Tanaquil, who knew a great deal about signs; and she said it meant that he would sometime be king of Rome. This prophecy pleased Tarquin very much, because he was ambitious and fond of ruling.

Tarquin and his wife were so rich and powerful that they were warmly welcomed by the Romans. They took up their abode in the city, spent their money freely, tried to make themselves as agreeable as possible, and soon made a number of friends among the patricians.

Ancus Martius became acquainted with Tarquin, and, finding him a good adviser, often sent for him to talk about the affairs of state. Little by little, the man grew more and more intimate with the king; and when Ancus died, after a reign of about twenty-four years, no one was surprised to hear that he had left his two young sons in Tarquin's care.

The Roman Youths

A

S

you have seen, the Romans were generally victorious in the wars which they waged against their neighbors. They were so successful, however, only because they were remarkably well trained.

Not very far from the citadel there was a broad plain, bordered on one side by the Tiber. This space had been set aside, from the very beginning, as an exercising ground for the youths of Rome, who were taught to develop their muscles in every way. The young men met there every day, to drill, run races, wrestle, box, and swim in the Tiber.

These daily exercises on the Field of Mars, as this plain was called, soon made them brave, hardy, and expert; and, as a true Roman considered it beneath him to do anything but fight, the king thus had plenty of soldiers at his disposal.

Ancus Martius had greatly encouraged the young men in all these athletic exercises, and often went out to watch them as they went through their daily drill. He also took great interest in the army, and divided the soldiers into regiments, or legions as they were called in Rome.

As the city was on a river, about fifteen miles from the sea, Ancus thought it would be a very good thing to have a seaport connected with it; so he built a harbor at Ostia, a town at the mouth of the Tiber. Between the city and the port there was a long, straight road, which was built with the greatest care, and made so solidly that it is still in use to-day.

To last so long, a road had to be made in a different way from those which are built to-day. The Romans used to dig a deep trench, as long and as wide as the road they intended to make. Then the trench was nearly filled with stones of different sizes, packed tightly together. On top of this thick layer they laid great blocks of stone, forming a strong and even pavement. A road like this, with a solid bed several feet deep, could not be washed out by the spring rains, but was smooth and hard in all seasons.

Little by little the Romans built many other roads, which ran out of Rome in all directions. From this arose the saying, which is still very popular in Europe, and which you will often hear, "All roads lead to Rome."

The most famous of all the Roman roads was the Appian Way, leading from Rome southeast to Brundusium, a distance of three hundred miles. This road, although built about two thousand years ago, is still in good condition, showing how careful the Romans were in their work.

The King Outwitted

T

ARQUIN

was the guardian of the sons of Ancus Martius; but as he was anxious to be king of Rome himself, he said that these lads were far too young to reign wisely, and soon persuaded the people to give him the crown instead.

Although Tarquin thus gained his power wrongfully, he proved to be a very good king, and did all he could to improve and beautify the city of Rome. To make the place more healthful, and to prevent another plague like the one which had killed Tullus Hostilius, he built a great drain, or sewer, all across the city.

This drain, which is called the Cloaca Maxima, also served to carry off the water from the swampy places between the hills on which Rome was built. As Tarquin knew that work properly done will last a long while, he was very particular about the building of this sewer. He had it made so large that several teams of oxen could pass in it abreast, and the work was so well done that the drain is still perfect to-day, although the men who planned and built it have been dead more than twenty-four hundred years. Strangers who visit Rome are anxious to see this ancient piece of masonry, and all of them praise the builders who did their work so carefully.

One place which this great sewer drained was the Forum,—an open space which was used as a market place, and which Tarquin surrounded with covered walks. Here the Romans were in the habit of coming to buy and sell, and to talk over the news of the day. In later times, they came here also to discuss public affairs, and near the center of the Forum was erected a stand from which men could make speeches to the people.

Tarquin also built a huge open-air circus for the Romans, who loved to see all sorts of games and shows. In order to make the city safer, he began to build a new and solid fortress in place of the old citadel. This fortress was sometimes called the Capitol, and hence the hill on which it stood was named the Capitoline. The king also gave orders that a great wall should be built all around the whole city of Rome.

As this wall was not finished when Tarquin died, it had to be completed by the next king. The city was then so large that it covered all seven of the hills of Rome,—the Palatine, Capitoline, Quirinal, Cælian, Aventine, Viminal, and Esquiline.

Soon after Tarquin came to the throne, he increased the size of the army. He also decided that he would always be escorted by twelve men called Lictors, each of whom carried a bundle of rods, in the center of which there was a sharp ax. The rods meant that those who disobeyed would be punished by a severe whipping; and the axes, that criminals would have their heads cut off.

Roman Lictors

During the reign of Tarquin, the augurs became bolder and bolder, and often said that the signs were against the things which the king wanted to do. This made Tarquin angry, and he was very anxious to get rid of the stubborn priests; for, by pretending that they knew the will of the gods, they were really more powerful than he.

The chief of these augurs, Attus Navius, was one of the most clever men of his time; and Tarquin knew that if he could only once prove him wrong, he would be able to disregard what any of them said. The king therefore sent for the augur one day, and asked him to decide whether the thing he was thinking about could be done or not.

The augur consulted the usual signs, and after due thought answered that the thing could be done.

"But," said Tarquin, drawing a razor and a pebble out from under the wide folds of his mantle, "I was wondering whether I could cut this pebble in two with this razor."

"Cut!" said the augur boldly.

We are told that Tarquin obeyed, and that, to his intense surprise, the razor divided the pebble as neatly and easily as if it had been a mere lump of clay. After this test of the augurs' power, Tarquin no longer dared to oppose their decisions; and although he was king, he did nothing without the sanction of the priests.

The Murder of Tarquin

T

ARQUIN

was called upon to wage many wars during his reign. He once brought home a female prisoner, whom he gave to his wife as a servant. This was nothing unusual, for Romans were in the habit of making slaves of their war prisoners, who were forced to spend the rest of their lives in serving their conquerors.

Shortly after her arrival in Tarquin's house, this woman gave birth to a little boy; and Tanaquil, watching the babe one day, was surprised to see a flame hover over its head without doing it any harm. Now Tanaquil was very superstitious, and fancied that she could tell the meaning of every sign that she saw. She at once exclaimed that she knew the child was born to greatness; and she adopted him as her own son, calling him Servius Tullius.

The child of a slave thus grew up in the king's house, and when he had reached manhood he married Tanaquil's daughter. This marriage greatly displeased the sons of Ancus Martius. The young princes had hoped that they would be chosen kings as soon as Tarquin died; but they saw that Servius Tullius was always preferred to them. They now began to fear that he would inherit the throne, and they soon learned to hate him.

To prevent Servius from ever being king, they resolved to get rid of Tarquin and to take possession of the crown before their rival had any chance to get ahead of them. A murderer was hired to kill the king; and as soon as he had a good chance, he stole into the palace and struck Tarquin with a hatchet.

As the murderer fled, Tarquin sank to the ground; but in spite of this sudden attempt to murder her husband, Tanaquil did not lose her presence of mind. She promptly had him placed upon a couch, where he died a few moments later. Then she sent word to the senate that Tarquin was only dangerously ill, and wished Servius to govern in his stead until he was better.

She managed so cleverly, that no one suspected that the king was dead. The sons of Ancus Martius fled from Rome when they heard that Tarquin was only wounded, and during their absence Servius Tullius ruled the Romans for more than a month.

He was so wise and careful in all his dealings with the people that they elected him as the sixth king of Rome, when they finally learned that Tarquin was dead. It was thus that the two wicked princes lost all right to the kingdom which they had tried to obtain by such a base crime as murder.