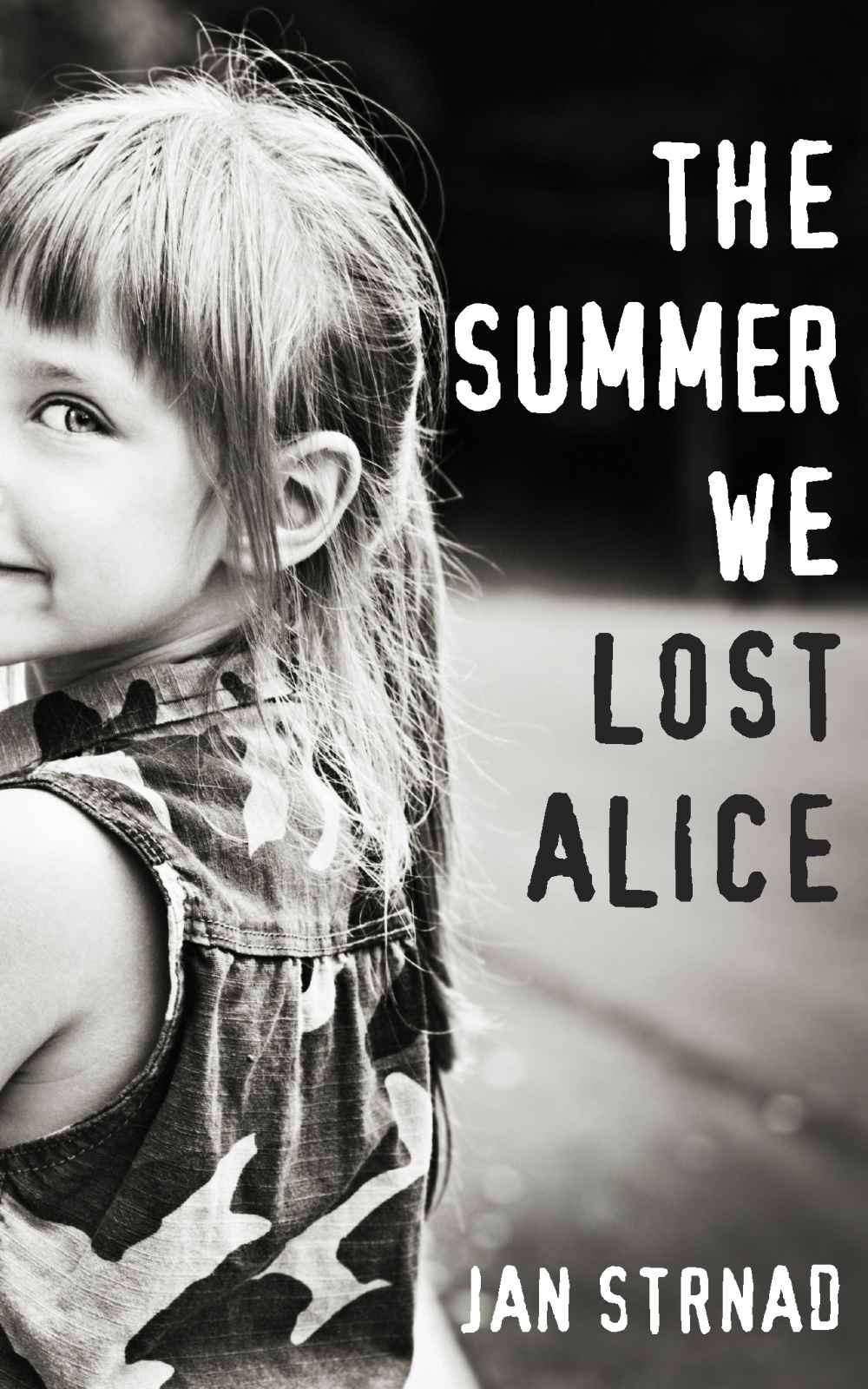

The Summer We Lost Alice

Read The Summer We Lost Alice Online

Authors: Jan Strnad

The Summer We Lost Alice

a

novel

by Jan Strnad

© 2012 by Jan S. Strnad.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright holder. Inquiries should be sent via email to [email protected].

Barbie, Ken, and Skipper are trademarks (TM) and © Mattel, Inc.

Cover design by Thinkmodern.com. Photograph by Imgorthand.

Proofreading by Diana Cox of novelproofreading.com

.

Encouragement and editorial assistance by Julie Strnad.

Part Two: Return to Meddersville

One: Ethan and Alice

I'M RIDING

on the bus with my mother. She's packing me off to Meddersville.

The air is hot and the seat is sticky

. My mother smiles when she catches me looking at her, but it's a tired smile that even a kid can tell is bogus.

I'm nine years old

. She, in her late thirties, seems old to me, maybe because she's dressed so plain. She has brighter dresses than the brown and yellow one with flowers she's wearing now, but Mom doesn't want to seem to be putting on airs in front of our small town relatives. We come from the big city, Wichita, Kansas, which has two hundred thousand people, but Meddersville only has four thousand, and most of them are farm folk or they're in businesses that cater to farm folk. Dad says that they're a different breed. Dad isn't with us. It's just Mom and me.

I'm going to spend the summer with my Aunt Flo, my Uncle Billy, and Flo's two kids, Catherine and Alice. Alice is just about my age, a year younger than me. Catherine is older, a teenager who is boy-crazy. I know from reading a letter that Aunt Flo wrote to my mother that Flo and Billy are worried that Catherine will get into

trouble, but they don't say what kind. When I ask Mom about it, she says it's none of my business and that I wouldn't understand anyway.

Before, Dad always drove us to visit Aunt Flo and Uncle Billy, but not this time. We have to take the bus because Dad needs the car to drive to work. I'm going to be staying in

Meddersville by myself for a while. Mom and Dad want me gone for some reason and I'm afraid that when I return, things will have changed. Maybe we'll be living in a different house or maybe Dad won't be there. I hear bits and pieces of conversations.

"Lower your voice. Ethan will hear." I hear that a lot lately.

I've never stayed away from home for more than a night, at a sleepover with a friend, and I don't like the idea of wasting what could be the whole summer in Meddersville. But something is going on—these are not ordinary times—and if I haven't been able to whine my way out of it by now I never will. I'm worried that if I'm too obnoxious about it, Mom and Dad will leave me with Aunt Flo and Uncle Billy forever. I'm trying to summon up my best behavior. It isn't easy, but I'm trying.

Gazing out the window at the barbed wire

flowing by, I sit up suddenly and whip my head around at something I've just seen—a turtle straddling a fence post. Its legs flail at the air but can't find anything to grab onto.

"Did you see that?" I say.

Mom says, "Uhm-hum."

"How'd it get up there?"

"Some fool put it there. Some fool who thinks he's clever, but instead he's just mean." She sees the look on my face and can tell that I'm worried about the turtle. "It'll fall off pretty soon," she says. "It'll be okay."

"How do you know?"

"Because I've never seen a turtle skeleton on a fence post," she says.

I look at the expanse of wheat outside the window and the endless sky looming overhead. A dust devil swirls, kicking up wheat chaff and dust. I don't like it out here. I remember seeing a movie where an airplane comes out of nowhere in a place like this and chases a man across the field, where there's nowhere to hide.

"What if a hawk gets the turtle before it falls off?"

"That won't happen."

"But it could."

"Lots of things could happen, but they don't."

She tells me to quit worrying about the turtle, but I can't. Things like this bother me.

Mom points out the grain silos that say "

Meddersville" on the side. She says we're almost there. She says it like it's a good thing. I'd rather ride on this bus with her for the rest of the summer than be left alone in Meddersville.

I have to find some way to kick myself off this post.

* * *

We drive past the little store and gas station on the edge of town and almost instantly we're pulling into "downtown." There aren't any tall buildings

. The tallest is maybe four stories high. It feels like a ghost town. There's hardly any traffic to speak of, and the few people on the sidewalk seem lost somehow, like they've found themselves here and they aren't sure where they're supposed to go next. They don't walk purposefully down the sidewalk like people in Wichita. They stop and talk with one another as if they have all the time in the world.

The bus circles a small park with a statue and a cannon and a six-sided building with no walls, then it stops in front of a drugstore. There's no station like the one in Wichita where we got on the bus, no depot. The bus lets us off at the curb and the driver takes our luggage out of the compartment and drives away. It feels as if we've been kicked off the bus and deposited any old place. It's hot and muggy.

It's cool, though, inside the drugstore and there's something friendly about it. It's air-conditioned, but old wooden ceiling fans turn slowly overhead, just for fun I guess.

In Wichita the drugstores are called "convenience stores" and they have anything you want to eat but no place to sit and eat it, which doesn't seem very "convenient" to me. The drugstore in

Meddersville has a counter with round seats that spin on ball bearings.

"When I was a girl," Mom says, "I would go to a drugstore like this one, with a counter like this one, and if no one was sitting there, I would run up and down and spin all the seats. There was a man on television named Ed Sullivan, and he used to show acts on his television show, and one of the acts was a man who spun plates on sticks. I used to pretend that each seat was a plate and I had to keep it spinning or the plate would fall off."

I ask if I can spin the seats.

"No. It's something you do when your mother isn't with you."

We sit at the counter, luggage at our feet, and drink Cokes, waiting for Uncle Billy to pick us up. I like this store with its counter and round seats that rumble as I swivel back and forth. I like the racks of cheap toys in blister packs, things you could just buy without having to save up your allowance. The shelves have everything you're likely to need, but not twenty different kinds so that you're overwhelmed with choices and come home with the wrong thing. "Just enough of everything you need." If I owned this store, I would write that on a sign out front.

I see a dusty station wagon pull up in front of the store and Mom says, "Here's Billy. Drink up."

She gathers our suitcases and is paying for our Cokes when Uncle Billy walks in. He smiles like a man who is used to smiling, like someone who would have to work on frowning about anything. He looks at me and greets me as if I'm the best person he could possibly want to see right now. He sells insurance for The Hartford, whatever that is.

He gives my mother a hug and smiles at her, but the smile he gives her is different from the one he gave me. There's something sad about it, something grown up

that I don't understand. Uncle Billy takes our bags and puts them in the back of the station wagon. Mom sits in the front seat and I sit in the back. The car smells like dogs. It has carried Uncle Billy down many a dusty back road and through many a farmer's field, sometimes in search of quail and pheasant, sometimes to survey the damage from a recent storm.

He reaches over the seat and hands me a pad of paper and a pencil. The paper says "Weaver Insurance Agency" and has a picture of a stag on the top, the company's emblem. While Uncle Billy drives and he and my

mom talk, I try to draw a stag like the one on top of the paper. My drawing sucks.

Uncle Billy and Mom talk about the weather and the bus ride and how everybody is doing, all the way to the house. Uncle Billy doesn't ask about Dad. I know it's because I'm there.

We arrive at Aunt Flo and Uncle Billy's house. It looks old but it has a large front porch with a wooden swing that appeals to me instantly. Our porch in Wichita is a concrete slab barely big enough for two people to stand on. The trees surrounding this house are bigger than ours, too.

Maybe it's just the trees and that's all there is to it, but Aunt Flo and Uncle Billy's house seems very different from ours. It looks like a house with a purpose, like something that belongs where it is, as if it grew out of the earth. Our house in Wichita looks like a green plastic

Monopoly house that was set down by a careless giant who never bothered to pick it up. I don't know any better way to explain it.

As Uncle Billy's station wagon pulls up the driveway, I see a huge black dog running toward the car. He gallops like a horse on long, strong legs. His name is Boo.

Boo thuds against the car door and pounds the window with his enormous paws. He mists the glass with his breath, slobbering a torrent as if he had a spit-hose up his behind.

Uncle Billy places one arm on the back of the seat as he turns around to face me. He smiles, as he always does.

"Don't worry about him, Ethan," Uncle Billy tells me. "That's just old Boo, remember?"

Oh, yes. I remember Boo.

MY AUNT FLO'S kitchen smells of old linoleum. At least that's what I think it is. I'm nine years old—what do I know? But the floor crackles under my feet, I know that much. The doors on the cabinets are made out of little boards a few inches wide. Our cabinet doors in Wichita are made out of a single piece of something that looks like wood but isn't. Aunt Flo's countertop is linoleum, like the floor, and there's a metal strip along the edge. Our counters in Wichita are smooth and hard and the edges curve up and then down, and I don't know what it's made of.

The water in

Meddersville tastes funny. When I complain about it to my mother she tells me to hush. Aunt Flo says, "The boy's used to city water, all full of chlorine. He doesn't know what it tastes like fresh from the well. I'll make some lemonade."

I think that means she's going to make Kool-Aid from an envelope, but instead she opens a large cupboard and pulls out a paper sack and inside are lemons. She cuts them in half one by one and squeezes the halves on a little pitcher-like bowl with a bump in the middle. After every few lemons she pours the juice and the pulp into a pitcher. It takes forever, and I think this must be how cavemen made lemonade.

"Don't you have Kool-Aid?" I ask. She smiles and gives my mother a look, then she pours the juice into a big pitcher and adds ice and sugar and water and stirs it with a wooden spoon. She pours some into a glass for me.

"Try this," she says, "lemonade from real lemons." I drink a little while my mother watches. It's too sour but I know I'm supposed to like it, so I say that it's good and plot how to add more sugar when no one's looking.

Aunt Flo says she'll make popcorn, too, for me and my cousin, Alice. She lights the burner with a match. Our burners in Wichita are electric and all you do is turn them on. She pours oil into a pan and gets out a package of corn. In Wichita, popcorn comes in little aluminum pans and the top swells with popcorn when you heat it.

Everything is different here. Everything smells funny, even the air, which is dusty and full of scents I don't recognize.

I remember the last time we came to visit. It was two years ago, I think. There were grasshoppers everywhere. Dad drove us up the highway and big, fat grasshoppers peppered the windshield like hailstones. Soon the windshield was so gooey with grasshopper guts that you could hardly see out of it and we pulled into a gas station even though we didn't need any gas. The grille was splattered with grasshoppers, some of them still stuck in the radiator and others that just left a yellow-green smear of guts behind. Dad scratched at the grasshoppers on the windshield and used about a hundred gallons of water to wash the front of the car off, including the headlights. He topped up the gas tank even though we had half a tank. He made a point of telling me why.

"It wouldn't be right, Ethan, to just use up the station's water and paper towels and not buy gas. We'll top up the tank so at least they don't lose money on us."

Five minutes after we left the gas station the windshield was as dirty as ever. Dad squirted the windshield with the squirter and ran the windshield wipers, but that only smeared the grasshopper guts out like paint. When we pulled up to Uncle Billy and Aunt Flo's house, they came out to greet us as if nothing was wrong at all, but the front yard was solid with grasshoppers. Their bodies crackled and popped as we walked on top of them to the house. You couldn't walk around them. They were like a writhing, fluttering grasshopper carpet everywhere you had to step. All you could do was crunch them underfoot.

Uncle Billy shook his head when my father mentioned it. "Happens every few years," he said. "I'll be out for the next three weeks solid, looking at fields and trying to figure the damage. We plan for it, though.

Hartford's rock solid. We'll make good. Always do."

I'm glad there are no grasshoppers this time.

They creeped me out. It was too easy for me to imagine them swarming over me, covering me from head to foot and eating me alive. I would try to scream but grasshoppers would fill my nose and mouth until I couldn't breathe. I fall to the ground and I hear people calling my name, looking for me, and I can't answer because of the grasshoppers clogging my throat. When someone does find my body, all they find is my bones, stripped clean in a matter of minutes like piranha fish do when you throw a cow into the Amazon River.