The Sun and the Moon: The Remarkable True Account of Hoaxers, Showmen, Dueling Journalists, and Lunar Man-Bats in Nineteenth-Century New York (2 page)

Authors: Matthew Goodman

The

Sun’

s astronomical series appeared at the end of an uncomfortable August. For nearly the whole month a hot, heavy dome of air had lain upon New York, materializing in the morning and evening into a peculiar thick fog of a sort no one could remember having seen before. The weather, the

Commercial Advertiser

remarked, was “fitful and cheerless,” and had “scarce deigned to smile upon us.” Men and women alike wore only white for their evening promenades around the Battery (including, for men, the low-crowned, broad-brimmed white hats that had come so much into vogue), seeking out the cool breezes that still drifted across the bay and brought a faint but bracing scent of the ocean. What shade the city offered— a store awning, an alley between buildings, the poplars lining Broadway—

was no match for a heat that seemed to emanate from the air itself.

Even the occasional afternoon thunderstorm brought little relief. The vehicles crowding the city’s streets—coaches, omnibuses, carriages, carts—were pulled by horses, thousands of them, and their manure piled up along the curbsides in great heaps that the summer rain dissolved into malodorous brown rivers that splashed even the most careful pedestrian.

Pigs roamed wild (“ugly brutes,” Charles Dickens called them after his visit to New York, comparing their brown backs to the lids of old horse-hair trunks), and while they were efficient enough scavengers of the garbage that otherwise would have rotted in the streets, they inevitably added their own contributions to those of the horses.

Still, though no one much liked to discuss the fact, it was undeniable that the most upsetting of the waste fouling New York’s streets was, in origin, neither equine nor porcine but human. The city was booming with

– 4 –

0465002573-Goodman.qxd 8/25/08 9:57 AM Page 5

Prologue: The Man on the Moon

new arrivals; New York had long ago surpassed Boston as the most populous city in the United States, and it would shortly surpass Mexico City as the most populous in North America. Incredibly, the city was now home to more than a quarter-million people. New York’s size was a source of real pride among the city’s residents, but it also created numerous problems, not least among them what to do with all of the waste that the population daily produced. For temporary storage, the city depended on what were called privy vaults, holding tubs dug beneath outhouses.

City regulations required the privies to be large, deep, and well constructed, but many of them had not been built to code, and even the ones that had been could not meet the demands made on them by an increasingly numerous and crowded citizenry. Often the privies backed up and overflowed, their contents seeping up from the ground, like nightmarish hot springs, into yards and streets.

Home and shop owners were supposed to regularly sweep the sidewalk in front of their property, depositing accumulated dirt and garbage in the middle of the street, but this was a regulation residents rarely followed; nor, when they did, was the garbage often collected. New York, the largest and most vibrant city in the Union, lived with the constant reek of putre-faction. Even—especially—on the warmest days, shop doors were kept always shut, so as not to admit the smell from outside. “A person coming into the city from the pure air of the country,” noted one New Yorker, “is compelled to hold his breath, or make use of some perfume, to break off the disagreeable smell arising from the streets.”

It felt that month as if the summer would never end, although by the second week of August dispatches were already coming in telling of sharp frosts in Buffalo and parts of Connecticut. This was especially good news for Buffalo, where the cholera had appeared earlier in the summer; similarly distressing reports had arrived from several of the mid-Southern states, and all through the hot months New York’s residents nervously monitored the weather, looking for the unusual conditions—pale and silvery skies, strong winds in the upper atmosphere, rounded cumulus clouds—that seemed to many to have presaged the afflictions of 1832: the “cholera year,” as it would always be remembered by those who had lived through it. In just two months the disease had killed 3,513 New Yorkers; all that summer the sky above the city had been filled with the oily, acrid smoke of clothes and bedding being burned in the houses of the dead.

– 5 –

0465002573-Goodman.qxd 8/25/08 9:57 AM Page 6

the sun and the moon

Those ominous weather patterns had not yet been spotted, but some unfortunates had been struck down in Buffalo, and until the cold weather arrived few New Yorkers could feel entirely confident that the disease would not hop aboard any of a thousand steamboats and make its way down the Erie Canal; thanks to the new canal, the trip would take little more than a week.

The cholera had managed to find New York the previous summer as well, although the toll proved not nearly as great as before, with deaths numbering in hundreds rather than thousands. In 1834 the more immediate concern had been not disease but riot: time and again that year armed troops had to be called out to protect New Yorkers from each other. In the cold April rains that accompanied the city’s first direct mayoral election, roving bands of Democrats and Whigs fought in the streets with clubs, hurling paving stones and brickbats plucked from nearby construction sites. Each side raged against the other: to Democrats, Whig politicians were hired lackeys of the city’s bankers and aristocrats, while Whigs denounced Democrats as ignorant roughs and “damned Irishmen” unworthy of political power. On the third day of violence, several hundred Whig supporters looted the gun shops of Broadway, then stormed the state arsenal and began arming themselves with swords and muskets. News of the attack quickly reached the ranks of the Democrats, and soon the arsenal was surrounded by a restless, angry crowd twenty thousand strong. Rumors circulated that the mayor was dead (he had been bloodied in an early skirmish), but he soon arrived at the arsenal, declared New York to be in a state of insurrection, and managed finally to restore order by calling out twelve hundred infantry and cavalry troops who marched down Broadway with bayonets and sabers drawn.

Sailors rioted downtown on Water Street, stonecutters uptown in Washington Square. A storekeeper on Chatham Street accused a woman of stealing a pair of shoes; a crowd gathered to defend her, and within an hour two hundred people lay injured. Every crowd, it seemed, had the makings of a mob. The worst violence came during three nights in July, when rioters, inflamed by lurid stories in some of the city’s merchant newspapers, attacked the homes, stores, and churches of blacks and abolitionists. (The abolitionists, it was rumored, were adopting black children; the abolitionists were asking their own daughters to marry Negroes; one abolitionist minister had even declared that Christ was a colored man.) For hours they roamed the streets in defiance of the local watch-

– 6 –

0465002573-Goodman.qxd 8/25/08 9:57 AM Page 7

Prologue: The Man on the Moon

men, smashing windows, ransacking houses, and hauling furniture outside to be burned. By the final night, when the rioters targeted the poor, racially mixed area of Five Points, the violence had escalated to a disturbing level of organization. During the afternoon, word passed through the neighborhood that, come nightfall, white families should light candles and stand by their windows, so that, in a grim burlesque of Exodus, they might be identified and their houses passed over.

Summers had proven perilous of late, and in the sweltering August of 1835 the city was stalked by the memories of its recent dead and wounded. Menace swirled in the air like the persistent fog, thickening as darkness neared. Feelings were running high against local abolitionists (or

“amalgamators,” as they were routinely called in the merchant papers, since the term “miscegenation” had not attained wide use). On August 21, a group of New York’s leading citizens gathered to plan a mass meeting in the park by City Hall as a way of demonstrating—especially to the city’s trading partners in the South—that New York would no longer tolerate abolitionist attempts to divide the Union by interfering with the rights of the slaveholding states. When the meeting was held on August 27, the mayor himself called it to order. By that time new, more sinister rumors were blooming everywhere. Heavy rewards had already been posted in several Southern cities for the capture of Arthur Tappan, a wealthy dry-goods merchant and New York’s most well-known abolitionist. Tappan had long been receiving threatening letters as a matter of course, but with the sense of danger intensifying, the mayor of Brooklyn, where Tappan lived, ordered nightly patrols of the streets around his house. Another prominent abolitionist, Elizur Wright, had reportedly barricaded his own doors and windows with planks an inch thick. The abolitionist Lydia Maria Child wrote to a friend from her home in Brooklyn, “I have not ventured into the city . . . so great is the excitement here. ’Tis like the times of the French Revolution, when no man dared to trust his neighbors.”

In such times, it was no surprise that New Yorkers sought diversion, and the city’s impresarios were happy to provide it. There were magicians, de-claimers, piano forte players, Italian opera singers. Uptown on Prince Street, Niblo’s Garden, the most fashionable of New York’s nightspots, had vocal and theatrical performances, and, between acts, fireworks.

Shakespeare, melodrama, and light comedy could be found at the city’s

– 7 –

0465002573-Goodman.qxd 8/25/08 9:57 AM Page 8

the sun and the moon

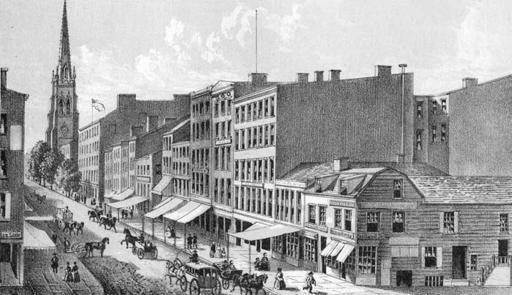

Looking south on lower Broadway in the year 1834. Trinity Church is in the background.

(Courtesy of the New York Public Library.)

many theaters, premier among them the Bowery Theater, the first American playhouse to have its stage illuminated by gas lights. By the end of September the Bowery would be presenting a new comic extravaganza,

Moonshine, or Lunar Discoveries,

inspired by the series of astronomical articles now being introduced in the

Sun.

Across from St. Paul’s Church, the City Saloon featured the local artist Henry Hanington’s peristrephic diorama “The Deluge,” an ingenious pairing of art and mechanical effects that transported the audience from the creation of the world through the Great Flood and the salvation by Noah’s ark. Within weeks Hanington’s most popular attraction would be “Lunar Discoveries,” carefully painted renderings of the moon’s waters, woods, and wildlife stretching across more than one thousand feet of canvas.

At night, Broadway gave itself over to spectacle. The low, grave hymns that seeped through the doors of Trinity Church and St. Paul’s in the mornings gave way to the high-pitched calls of the ticket takers, beckon-ing the crowds that surged along the boulevard. In just a few blocks, New Yorkers could sample what seemed to be all the exotica the world had to offer: stuffed birds and reptiles, tropical fish, fossils, shells, corals, miner-als, wax figures, Egyptian mummies, Indian utensils, Indian dresses, and sometimes the Indians themselves. Peale’s Museum, across from City Hall, was now featuring a “living ourang outang, or wild man of the woods”

– 8 –

0465002573-Goodman.qxd 8/25/08 9:57 AM Page 9

Prologue: The Man on the Moon

named Joe; the creature—as the newspaper advertisements did not fail to mention—had been wrenched from his mother’s breast (“which required considerable violence”) after she had been shot by hunters near the River Gabon in West Africa. Appearing with Joe was a fourteen-foot-long ana-conda from Bengal that every Monday noon was fed a living chicken; to the surprise of its handlers, on June 30 the snake had swallowed a woolen blanket whole. Around the corner, Scudder’s American Museum was exhibiting the “living Ai, or Sloth,” which captivated audiences with its woebegone expression and apparently indomitable apathy. The more compelling attractions, though, were always the human ones, such as Emily and Margaret Martin, known theatrically as the Canadian Dwarfs, who were playing a limited engagement at Scudder’s. One of the Martin sisters was said to measure just twenty-two inches from the ground; the other, though slightly taller, could converse with onlookers in both English and French.

Even that, however, could not compare with the attraction on view that summer in the Diorama Room upstairs at Niblo’s. Her name was Joice Heth, and she had been born a slave in Virginia—reportedly in the year 1674, which made her 161 years old at the time of the exhibition. More extraordinary still, Joice Heth claimed to have been George Washington’s nursemaid, and though blind and toothless and paralyzed on one side, she regaled her audiences with anecdotes of her young charge, whom she called “my dear little George.” Day after day the

Sun

and the city’s other newspapers brought fresh reports of “the old one,” as she quickly came to be known around town. Her wizened appearance was compared to an Egyptian mummy, a bird of prey, and the shank end of a piece of smoked beef.

“The dear old lady,” editorialized the

Spirit of the Times,

“after carrying on a desperate flirtation with Death, has finally jilted him.” That summer the city was flooded with handbills, pamphlets, and posters illustrated with Joice Heth’s portrait, and the newspapers regularly received large advertisements, all of this publicity having been organized by her new promoter, who was already displaying a flair for the uses of the public press.