The Supremes: A Saga of Motown Dreams, Success, and Betrayal (37 page)

Read The Supremes: A Saga of Motown Dreams, Success, and Betrayal Online

Authors: Mark Ribowsky

Tags: #Supremes (Musical Group), #Women Singers, #History & Criticism, #Soul & R 'N B, #Composers & Musicians, #General, #United States, #Biography & Autobiography, #Pop Vocal, #Music, #Vocal Groups, #Women Singers - United States, #Da Capo Press, #0306818736 9780306818738 0306815869 9780306815867, #Genres & Styles, #Cultural Heritage, #Biography, #Women

At the Cumberland, the Supremes were checked into a penthouse suite down the hall from Gordy’s, accessible by a private elevator that bypassed the rest of the company on lower floors. Most of the interviews set up with the British press were with Ross, with a peep here and there from Wilson and Ballard. It was as if all of Motown had turned out in England as courtiers in the court of Queen Diana.

This was abasing to most, but for Martha Reeves it was humiliating. Reeves, after all, had been the stimulus for the Revue’s first gig on the tour, a March 18 appearance on a BBC-TV show, “The Sound of 0306815867_ribowsky:6.125 x 9.25 4/22/09 11:06 AM Page 198

198

THE SUPREMES

Motown.” This, an hour-long special produced by the weekly program

Ready, Steady, Go

and hosted by Dusty Springfield, had come about because Springfield was enamored with Motown and especially with the Vandellas’ butch but slinky lead singer. When the show was pitched to the BBC, Springfield wanted the Vandellas to be the featured act, an idea that was nixed by the network and by Gordy.

There may have been more to Springfield’s preference than merely her musical tastes. Early on the tour, she was in Martha’s room and fell asleep. Reeves later recalled that “I just let her sleep and I covered her with a comforter as any friend would.” The next morning, Mickey Stevenson came to the door to inform Reeves of a schedule change and when she opened the door, he saw Dusty, “with one of her legs sticking out from under the comforter—fishnet stockings and all.” Stevenson apparently couldn’t wait to spread the news and in no time “all the men kidded and teased me as though something odd had happened.” The story became a spicy staple of Motown lore, reprised when Springfield came out of the closet years later, leading Reeves to finally address that “odd” night in London by saying, absent of a direct denial,

“I was amazed at just how others regarded our friendship, but I couldn’t care less what anyone thought.”

Reeves and the Vandellas were permitted to do a duet with Springfield on the show, but in rehearsals the producers and director fawned on the Supremes. For the finale, when all the acts were onstage as Smokey and the Miracles would perform a wild, extended version of

“Mickey’s Monkey” in stage center, the Vandellas, Temptations, and Stevie Wonder were to line up stage left; the Supremes were placed prominently, alone, just to the right, where they could be seen interact-ing with Smokey—this time, unlike at the Apollo, there’d be no need for Diana to elbow her way to get next to him. They’d also be given three numbers to sing on the show, including the first public unveiling of “Stop! In the Name of Love.”

Even so, Diana, as in the past, grew frantic watching the other acts in rehearsal going through their electric paces. Realizing the Supremes couldn’t get away with their quiescent “little kicks” in this setting, according to a tale in

Call Her Miss Ross

, she charged into the men’s room while the Temptations were in there making a pit stop and, between the urinals and stalls, bellowed, “We need some choreography quick for

‘Stop! In the Name of Love!’” whereupon the guys zipped up and taught her what would become the Supremes’ signature gesticulation: right hand straight out, palm forward, left hand on hip as they jointly 0306815867_ribowsky:6.125 x 9.25 4/22/09 11:06 AM Page 199

“ECSTASY TO THE TENTH POWER”

199

and dramatically emoted “Stop,” then slowly lowering the right arm, with fingers snapping in a cool, circular motion—a freeze-frame of precious, adorable haught, which, when prefaced by the story of a blinkered Ross barging into a men’s room to make it happen, seems a perfect allegory. If only it wasn’t perfect balderdash.

“Nah, it wasn’t in no men’s room,” says Otis Williams, “although Diana was bold enough to do that. It was at the Cumberland. We were all rehearsing in the ballroom and Paul [Williams] saw the Supremes doing the song and had an idea. Paul was a great idea man when it came to moves. It was really Paul, not Cholly [Atkins], who choreographed the Temptations. And he knew he had a killer move for the girls, and that the word ‘stop’ was the crux of the whole thing; everything had to come to a stop with a nice visual effect.”

“Paul told them, ‘Hey, do this here’—and made like a traffic cop.

He worked it out with them in, like, five minutes and they had their move. They loved it, too. ’Cause they always wanted to do more physical stuff than Berry or Cholly let them do.” This, Williams believes, was an indicator of a deeper resentment of how overly processed they had become. He went on: They’d gotten to the point where they were getting to hate the Broadway-Vegas kind of thing. Even Diana. I mean, she’s often blamed for the group going in that direction, but that ain’t so; it was all Berry. Diana wanted to be a blues singer, like Billie Holiday. She was actually very rebellious of doing all that “top hat” stuff. All of them were—hell, we were, too, ’cause they made us do the same thing when the Supremes were such a success with it.

Flo hated it the most. Flo just wanted to go out and sing and not have to smile like a Barbie doll. That wasn’t Flo. And, I’ll tell you, I think she held back a little on those numbers. You can see it in the old videos. She’d be a little off, a little stiff. She was a good dancer so she could pull it off not giving her all, and she’d give you that little look, that gleam in her eye, that all this was bull. That was Flo, man. She was the most real, funniest person I knew. She was really good-natured and down to earth, not like what they wanted the Supremes to be. People loved that in her. But I think as time went on, Berry didn’t like it.

0306815867_ribowsky:6.125 x 9.25 4/22/09 11:06 AM Page 200

200

THE SUPREMES

The tour proper began on March 20 at the Astoria Theatre in Finsbury Park. From there, it ran nearly nonstop until the April 13 finale in Paris at the Olympia Music Hall, with only two days idle in between. Along the way, the Revue would come through country towns and working-class ports, including Hammersmith, Bristol, Bournemouth, Leicester, Sheffield, Luton, Cardiff, Wolverhampton, Liverpool, Manchester, Portsmouth, and Leeds. On April Fool’s Day, it hopped across the border to Glasgow’s Odeon Theatre.

The whole time, no one had to guess where Gordy’s allegiance was.

As Mary Wilson recalled, “Berry never let us out of his sight, and I began to think of him as the fourth Supreme.” Separating frequently from the troupe, the “four Supremes” headed off for private receptions at cas-tles and palaces, having tea and crumpets with the likes of Lord and Lady Londonderry, in whose grand estate they all stayed for a week between shows (though for some reason Gordy didn’t take them when he was called to meet the Beatles at the Pinewood movie studio where they were filming

Help!

).

It was, said Wilson, astutely, “like living in a fairy tale, not only for us but for Berry, too. We [all] realized that we were going to make it—

and bigger than we ever imagined.”

Nor did it seem to matter to Gordy that there were three other big Motown acts somewhere in England, as well, who might have wanted to tell him, “Hey, Berry, remember us?” Or that the tour turned into what Wilson calls a financial “flop.” The first two weeks, it became evident that the Brits weren’t overly interested. Some shows were sold out, some embarrassingly undersold. Plainly, Gordy had read too much into the record sales racked up by Mary Wells and the Supremes across the pond. That, and all the testimonials in the world from the Beatles weren’t enough to sell seats in a land where Motown was still a hazy entity, its artists not regularly heard on the airwaves until recently.

Things picked up in the third week when the BBC-TV show was broadcast, but even so the most warmly received act on the bill each night was the middling British singer Georgie Fame and his band the Blue Flames, whom Gordy had contracted to warm up the audiences.

In the end, Motown lost several hundred thousand dollars on Gordy’s ambitious idea, though it did help establish the Tamla-Motown brand in Europe.

Gordy, though, seemed for once not to be thinking primarily of the bottom line (never mentioning that aspect of the tour in his memoirs), too focused was he on getting Diana’s bottom line into one of those an-

insert:Layout 1 4/22/09 11:08 AM Page 1

Milt Jenkins, the hustler who

created the Primettes, flashing

a million-dollar smile, poses

in one of his quieter suits in

his “office” at the Flame Show

The Primettes, circa 1959. In the beginning, there were four.

Bar, where a fist hole in the

But Betty McGlown, at far left, decided to get a real job.

From

wall was just part of the decor.

the author’s collection

Courtesy of Maxine Ballard

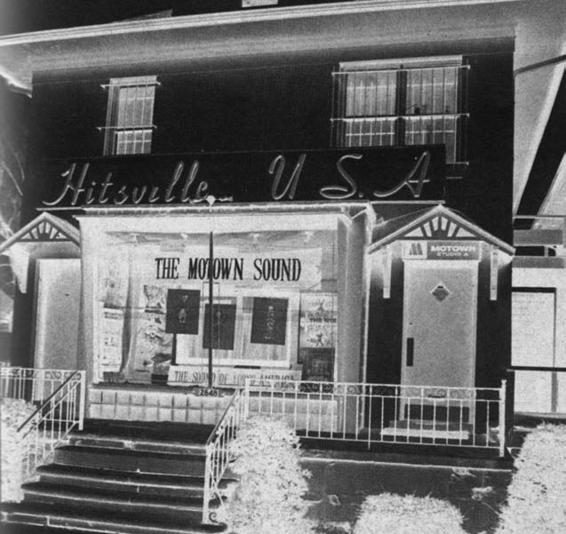

Hitsville, U.S.A. was the hub for young Detroit soul singers, and where the Primettes hung out trying to get noticed by Motown president Berry Gordy.

From the author’s collection