The Tea House on Mulberry Street (23 page)

The glass brooches glittered in Beatrice’s hand, a gift from Eliza’s lover. The brooches knew the answer: a German-born man by the name of Leo Frank was their real father, his genes succeeding where William’s had failed. Leo’s Israeli origins were plain to see, in the faces of his twin daughters.

Beatrice put her hand up to her neck, and coughed again. “We are not the children of William Crawley, war hero,” she said softly, and a tear rolled down her cheek.

“You mean, Mother had an affair?” Alice’s face was white.

“It looks that way. Mother always told us she lost the certificate during a house move. We are one year younger than we thought.”

“Oh, Daddy, dear Daddy,” whispered Alice. “I don’t believe it! It’s just a clerical mistake they made in the office, some silly girl with only half her mind on the job.”

Beatrice shook the box and a tiny photograph fell out. It was faded and cracked. The picture showed their mother in her nurse’s uniform, standing on the steps of The Royal Victoria Hospital, beside a tall man wearing round spectacles and a tiny black hat on the back of his head. On the back was written:

Eliza and Leo, 1941

. The man had his arm round their mother’s waist. Eliza’s stomach was slightly swollen. Beatrice and Alice had the same dark eyes and long straight nose as the man in the photograph.

Alice said, “That’s one photograph we won’t be giving to the City Hall.”

Beatrice said, “You know this means our father might have been a man of the Jewish faith? Look at that little hat he is wearing – I think they call it a yarmulka.”

“You mean, he was a Jew?” said Alice, and she put her hands up to her mouth.

“I think we must consider that to be a definite possibility,” said Beatrice, gently.

“But how can this be? Mother was a good woman. Perhaps she was the victim of a savage attack. One reads such awful things in the papers.”

“Alice, look at the photograph. Mother is smiling. Can you not see the resemblance between that man and ourselves? I’d prefer to be the result of a love affair, wouldn’t you? Not something terrible, such as an attack. You have heard of such affairs happening in wartime. People are vulnerable to temptation when their spirits are low,” whispered Beatrice. “For all Mother knew, she would never see her husband again.”

“But that means Mother was a sinner, fallen by the wayside, cast out into darkness.” Alice was beginning to panic.

“Stop it,” said Beatrice, dabbing at her eyes with a tissue. “Stop it, please. Don’t say things like that about Mother. I couldn’t bear it. I really couldn’t.” They went downstairs and sat in the parlour drinking cup after cup of hot, sweet tea.

“I feel different, now. Are we different? Are we Jewish?” Alice asked.

“No. We were raised as Christians and that is what we are.” Beatrice was sure about that. “Although, they do say the Jewish people are a hard-working race, with strong family values. And of course, they put great store by education.”

“Oh! Yes! And we were teachers! Should we tell anyone?” asked Alice.

“Oh, no. Definitely not. I don’t think so. After all, what would be the point? We have no surname, no clue as to his identity,” said Beatrice. “He may not have been the one who – who – he may not be our father.” Beatrice didn’t want to suggest that Eliza might have known other lovers as the bombs fell. Alice missed the point.

“But, there cannot have been too many Jewish people here during the war. Perhaps there is a list somewhere? Of refugees? We may have a family somewhere?”

“No. They didn’t want us to know about this. We will go on as if nothing had happened.”

It was then Beatrice noticed a tightly folded piece of paper on the ground – it must also have fallen out of the box. She opened it up. It was a telegram.

“What does it say?” urged Alice.

Beatrice hesitated. She feared it would confirm what was already too obvious. It did.

“

Congratulations, my darling. We wanted a baby and now we have two. You choose the names and keep our children safe. I want only to come home to you, and hold you in my arms forever.

Your loving husband, William

.”

“He was a true hero,” whispered Beatrice. “Never, not even once, did he make us feel we were not his children.”

“That’s true. Men of that calibre just don’t exist any more!” Beatrice said tearfully. “I miss him so much!”

“We both miss him, sister dear.”

They held each other close and wept for a little while.

Then, Alice almost had a heart attack with delayed shock. “Oh, my God,” she said. “Are we half-

German

, do you think?”

Chapter 28

A

P

RESENT

F

OR

B

RENDA

Mrs Brown stood ringing the doorbell of Brenda’s flat. In one hand, she held a large, brown-paper carrier-bag.

“Surprise!” she called, when Brenda opened the door, blinking repeatedly in the harsh daylight.

“What is it, Mum? I’m busy working on my paintings for Galway.”

“I know you are, sweetheart. And that’s why I’ve bought you a lovely present. I think it may be valuable, though I got it for twenty pounds in a sale.”

“Oh, great! Is that it, in the bag?”

“Of course. Now, let me come in, will you? It’s heavy.”

Brenda was thrilled. Things were definitely looking up in her life, she thought. About time, too. It had taken her hours in the unemployment office to have her benefits re-instated, after her dismissal from the supermarket.

Mrs Brown closed the front door behind her and trotted up the narrow stairs after her daughter. Brenda was hopping from one foot to the other, in the tiny hall, with sheer excitement. But when her mother opened the bag, Brenda wasn’t sure what to think. It was a very ornate frame, gold-coloured, with carved fruit and flowers at the corners.

“Ta-da!” cried her mother. “Now, what do you think of that?”

“Mmmm,” said Brenda. “I don’t usually have my paintings framed, Mum. That’s why I paint the sides of the canvas, you see? It’s my trademark. And I don’t think I have one that would fit those dimensions, either. Mine are all square-shaped.”

Mrs Brown was upset that her great surprise had fallen a bit flat. She pursed her lips and dropped the lovely frame back in the bag. “Never mind. I thought you’d love it. You could have painted something to fit in it, and it would have been the main attraction in your exhibition.”

“I don’t know…”

“Sure, aren’t Vincent what’s-his-name’s pictures all framed in gold? Honestly, Brenda! I thought you’d be pleased.”

“I am pleased, Mum. It’s a lovely present.”

“Do you want me to take it away? I suppose I can sell it on.”

“No, no. Not at all. Here, give me it. It’s a lovely treat for me. Very fancy, indeed. Will we have a coffee to celebrate?”

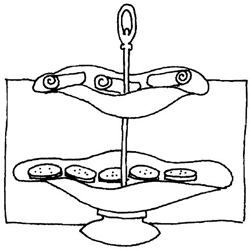

“That would be lovely. I bought you this as well.” And she produced an antique cake-stand from the bottom of the bag.

“Thanks, Mum! This is really smashing.” Brenda wanted to be sure she sounded grateful. She reached out her hands for the gifts.

“Oh, good. I knew you’d be pleased.” Mrs Brown was convinced she had chosen the right gifts. She handed them over.

The two women went into the kitchen and Mrs Brown sat down at the little table while Brenda made the coffee.

“I’m sorry, I haven’t a biscuit in the house,” said Brenda. Mrs Brown pulled a packet of peanut cookies and a box of mini-rolls from the pocket of her anorak.

“When have you, ever?” she smiled. “You’re a true artist, Brenda. You’ve no notion of the real world at all.”

“Well, I think that’s not such a bad thing,” replied Brenda. “I find the real world a bit of a disappointment. So, tell me, have you been busy recently?”

“Oh, yes. I have. I’ve sold seven car-bootfuls of your father’s old junk. I’ve made a fortune.” Mrs Brown opened the box of rolls and the glossy packet of cookies and placed them on the cake-stand.

“Mum, he’ll go berserk.”

“Well, I only sold the stuff he didn’t want any more. Records, out-of-date clothes, books, ashtrays. And since he moved out of the house, and set up home with that harlot from Dublin, nothing I do is his business any more.”

“I suppose so,” Brenda sighed. “I’m still getting over the shock. Are you coping okay on your own, Mum?”

“Not too bad. I’ve been to a Daniel O’Donnell concert with the girls from work. Daniel’s a great tonic for a broken heart.”

“That’s nice.”

“And we’re going to a new line-dancing club at the weekend. You know, we’re thinking of organising a trip to Nashville.”

“Mum! You’re a fast mover!”

“Well, at my age you can’t afford to mope about for ten years when your husband decides he doesn’t love you any more. I refuse to turn into a gibbering wreck.”

“He’ll be back, you know, Mum. This fling won’t last. He’ll be down on his knees at the front door, in less than a month, begging to get back into the house, I promise you. Harlots never make good housewives.”

“We’ll see. Meanwhile, I’m going to get out there and enjoy myself. And if you’d any sense, you’d do the same, instead of being cooped up all day in this poky wee place. Now, will you let me take a couple of these pictures of yours? I’m going to a boot-sale in Lurgan tomorrow. There’s always a few well-heeled people about Lurgan.”

“I won’t even dignify that with an answer.”

“Suit yourself. Well, I’m off.”

“Won’t you stay a while?”

“Can’t. The decorators are coming to paint the lounge at eleven. I’m having the whole place brightened up. Maybe you’d do a nice wee landscape for me, when you get the time?”

“Okay – cheerio, then.”

“Bye, love. Here’s a few quid for you, pet.” She handed Brenda forty pounds. “And don’t spend it all on paint. Do you hear me, now? Get yourself a few square meals next door.”

“Thanks, Mum. I love you.”

“Good job someone does. Right! I’ll be off. Be sure and lock the door behind me. I don’t trust this neighbourhood.”

When her mother had driven off, Brenda knelt down on the floor and examined the picture-frame in more detail. It was hand-carved from real wood. Could that finish be genuine gold-leaf? Covered in thick, sticky dust, it was, with threads of canvas hanging off the back, where the original painting had been torn away. Brenda began to think that her mother was right. This frame might be worth money; it did look like the real thing, not a moulded reproduction. She would clean it up, and use it, after all.

In mounting excitement, she found a ruler and measured the sides. She would make up a canvas to fit this frame, and hang it in a quiet corner of the gallery in Galway. Somewhere, where it would not distract from the other, unframed pieces. A little piece of whimsy, perhaps, that the critics would remember when they were writing their reviews?

She made another cup of coffee, and nibbled her way through the rest of the peanut cookies, wondering what she would paint. It was a good omen, the timely arrival of this golden picture-frame.

Chapter 29

T

HE

C

RAWLEYS

M

EET THE

Q

UEEN

Alice crossed off the days on the calendar until the 26th of September arrived. The Crawleys were due to attend their special lunch at City Hall that afternoon. They got ready in complete silence, and stood side by side before the hall mirror as they pinned on their mother’s brooches. A sudden tooting from outside told them the taxi had arrived.

“Come on,” said Beatrice. “The sooner we get this over with, the better. Now, remember; think twice before you open your trap. If this gets out, we’re finished in the rambling club.”

“Don’t worry. Wild horses wouldn’t drag it out of me. I just hope there aren’t too many snobs about the place. Have you noticed how these special occasions seem to bring out the worst in people?”

They sat in the back of the car as if they were on their way to be executed.

“Where are you off to, the day?” asked the driver. “All done up like you are?”