The Trial Of The Man Who Said He Was God (12 page)

Read The Trial Of The Man Who Said He Was God Online

Authors: Douglas Harding

Tags: #Douglas Harding, #Headless Way, #Shollond Trust, #Science-3, #Science-1, #enlightenment

Addressing this vital issue of where, I’m much less interested in what you say than in what you do, in your approach to your work as a brain surgeon. I mean

approach

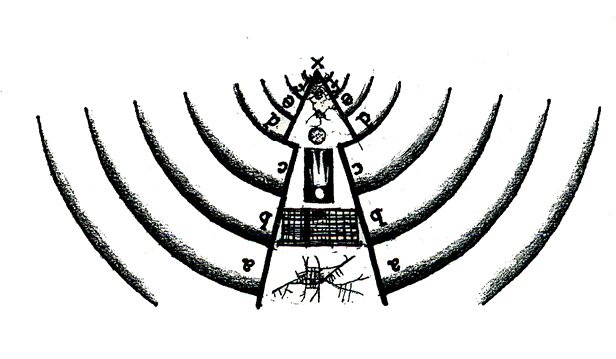

literally, in the most physical sense of the word. By what steps (I’m asking) do you get down to work daily, actually come to the delicate task of (say) excising a tumour on my brain? It will save the court’s time if you will let me outline the successive stages of your inward journey, for you to confirm or correct as needed. These stages I’ve shown on Diagram No. 8 in the booklet, which you and His Honour and the Jury should please refer to throughout.

Diagram No. 8

You drive from the country to the town (a), and through the town to the hospital (b). Having parked, you walk to the neurosurgical department and enter the scrub of the operating theatre that’s been allocated to you. Scrubbed and gloved and gowned, you approach the patient (c) on the table, already heavily sedated and anaesthetized locally. (The brain itself, of course, is insensitive to the scalpel, and needs no anaesthetizing.) You commence surgery, making incisions and trepanning and so on, till the cortical area requiring treatment is exposed and clearly on view (d).

In short, you have approached me by stages, beginning with a landscape and ending with a brainscape.

Is my account of your professional procedure, so far, about right?

WITNESS: I can’t fault it. But why this painstaking detection of the obvious? So what?

MYSELF: Now we’re coming to the really interesting part, the nitty-gritty.

Here, in region (d), which is still several inches short of me, you stick.

You the brain surgeon have arrived at your goal at the place from which my cortex can be viewed. Note how far it is from me, the operand, how far it has to be from the point of contact (x). For if (armed with optical and electron microscopes) you were to venture much nearer, you would be wasting precious time and holding up the operation. Leaving behind you the region where the brain is on display, you would come to regions where it’s replaced by a set of neurones (e), then one neurone (f), then a bunch of molecules, then one molecule . . . And so on until, having come all the way in to our meeting place (x), you would have left all of me behind you. And what good would that do either of us? So it’s essential to the operation that you stop short of these forbidden regions, and remain at just the right distance (around nine inches, say) from where I am. Essential that you don’t stray from the only region where my brain’s on show, the only region where it puts in an appearance, where

qua

brain it manifests.

WITNESS: Are you saying that I make an incision in the brain tissue

at a distance?

I’m no magician.

MYSELF: I was coming to that. Plainly it’s not you the man but your outstretched scalpel-hand that travels that last and all-important stage of the inward journey (d, e, f . . . x), through regions cellular and molecular and atomic and subatomic, to the point of contact (x), the site of the operation itself. It’s not you the surgeon but the keen edge of your knife that traverses these near regions where I’m progressively brainless, then cell-less, then molecule-less, and so on till it arrives

here

where I’m everything-less. Here we really come together. Here at last we two get down to business.

WITNESS: I think you’ve got the pattern all right. But I’m having difficulty with the language.

MYSELF: In that case, let’s go non-verbal and refer again to our picture, showing the main stages of your approach to me, your patient. My point cannot be missed, it’s so obvious. It’s simply that, if you are to keep abreast of the progress of your operation on my brain, you must stay with it where it manifests, where it’s on display — just so many inches short of that busy scalpel.

The question was: where do I keep my brain? And the answer is: in roughly the same place as I keep my head; namely, upwards of (say) nine inches from here, from my Centre. I stash it away where I stash my head — that little head which I keep over there in my mirror and in people’s cameras and in you people, and never, O never, here. (How ridiculous that Nokesian pinhead — with its even tinier brain — would look on these immensely broad shoulders!) Naturally brain and head go together — and naturally, knowing their place, go to it together. This would be obvious if it happened (as it could well happen in some brave new world) that my scalp and skull were replaced by transparent plastic, and instead of a hairdo I wore a braindo.

Well, I put it to you, the Witness: is this soft British whimsy or is it hard international facts? Isn’t your approach by stages to this operation a telling example of Basic Relativity, of the Law (so fundamental, so neglected) that what a thing

is

is no fixed quantity/quality, but depends on where it’s being viewed from? Of the Law that

distance,

besides lending enchantment, Iends just about everything else, and is the making of things? Of the Law that whatever I go up to I lose, and that what I always go up to (namely, my head and brain) I always lose — lose to you and to the world in general? Which explains why you, in your role of brain surgeon, know your place — as we have seen — and come no nearer. Yours is close work, all right. But not too close.

Not disagreeing, Witness says it all takes a lot of getting used to: it’s so different from the ordinary common-sense way of looking at his job. But he’s not clear about why we should bother with this strange and therefore difficult vision, so long as the ordinary one works as well as it does.

MYSELF: I can think of two good reasons. First, if it’s a true and sensible vision that makes nonsense of our so-called commonsense picture of what’s going on (and by God it does!), then we’d better pay attention. Lies are inefficient, truth works. Lies bind, truth liberates. What’s even more to the point, lies kill but truth cures.

Second, if it proclaims my true Identity (and by God it does, it does!) — assuring me of my oneness with the One Who as the Source of all things is No-thing, and happily as free from brains as from everything else — then it’s the best news imaginable. It’s the good news I’m dying to hear and living to put into practice. It’s the revelation of What I need, not only to survive this Trial and the severest sentence the court can impose, but also to ensure that what survives is worth surviving for. In brief, the more I enjoy this vision the more I find it to be realistic, down-to-earth no less than up-to-heaven, practical, beautiful, and all my heart could desire.

COUNSEL, unable to contain himself any longer: Also it’s flim-flam, a load of wishy-washy willful thinking. [He jabs at me with a bony forefinger.] For you haven’t begun to face the disagreeable fact that, as the Witness brought out, this much-cracked-up consciousness of yours (on the alleged primacy of which your case hangs) arises from and is conditioned by the brain. Airily you ignore the inconvenient fact that it is in all ways dependent upon that organ’s bulk and complexity, and its state of health or sickness. Here the Witness’s testimony implies that this wonderful awareness, this precious consciousness of yours which you presume to deify, is about as Godlike as marsh gas, which also is beautifully at-large and transparent and colourless and tasteless, and sometimes luminous — but which bubbles up from rotting vegetation. Now I ask you: what sort of God is this, who bubbles up from a tangled mishmash of knobbly grey matter, matter which, if not rotting fast, is still suffering from a terminal disease called life, and is tragically subject to tumours, cancer, blood clots, drugging and other horrors? I ask you! [He leans far forward. His voice drops from a roar to a stage whisper.] Listen, Nokes! Listen very carefully. With the utmost seriousness I mean what I’m about to say. If you will assure the court that

this

is the divinity you claim to be — I refer to this will-o’-the-wisp or flibbertigibbet — then you are indeed a fool, and indeed you are guilty of gross abuse of the English language, and probably of behaviour leading to a breach of the peace.

But not of blasphemy.

Redefine your deity as a pseudo-gaseous by-product of matter, or, if you like, as its finest production to date, and a lovely quasi-spiritual phosphorescence playing above the stuff (rotting or daisy-fresh, I don’t care) — go on to apologize to the court for wasting all this time — and I will see that the charge against you is dropped … Mind you, I’m not saying that a lesser one, to be tried in a lower court, won’t be preferred against you. But at least your life won’t be at stake … Well, what about it?

The Judge nods vigorously. Counsel sits himself down with the insufferably complacent air of a parent who magnanimously pardons a rebellious and rather idiotic child, in the expectation of tearful gratitude. The Jury are all ears.

MYSELF, treating this peace-feeler with the contempt it deserves, and taking the war into the enemy’s territory: Do I gather that Counsel is gassing away in this court? Am I to understand that the forensic fireworks we’ve just witnessed are a kind of ignis fatuus arising from a kind of bog? Well, he’s the final authority on what it’s like being that bog, and I’m in no position to pull him out of it. All I can say is that he’s reduced his arguments throughout this Trial to wind, to hot air, to miasmic hot air at that. Happily my awareness isn’t a bit like that. Sure, it can’t be pinned down (much less bogged down), baffles all description, is quite indefinable. But it’s indefinable because it’s the Definer, the Fountainhead of all definition. The reason why I can’t tell the court what it’s like is that it isn’t

like

anything, that it differs absolutely from everything it’s conscious of. The reason I’m tongue-tied on this subject (which is

the

Subject) isn’t that I don’t know what it is, but that it’s the only thing I do know — know through and through

ad infinitum,

know absolutely because I am it absolutely. All other entities (yes, including brains and heads) are the

contents

of this Container which never changes, while they change all the time, come and go continually. Moreover, in razor-sharp contrast to their Container (which stands forever perfectly revealed, yet perfectly mysterious) they are painfully shy and retiring, never exposing all sides of themselves, let alone their insides. In fact they are cagey by nature, essentially lacking, never all there, never quite real. To see them at all is to see them distorted. Such reality as they can boast (and this goes for brains of course) isn’t theirs at all, but on loan from the One Reality that is Consciousness, the Awakeness from which they arise and to which they return. Ladies and gentlemen of the Jury, to make this Primary Producer a by-product of one of its products is like attributing Walt Disney to Mickey Mouse, Edison to his lamp, and Sir Gerald to his brief. It is to derive the Real from the unreal, the True from the false, the Known from the guessed-at. And it’s just plain dotty!

COUNSEL, stamping and finger-wagging: But you can’t wriggle out of the fact that, in the course of your own evolution, so swiftly recapitulated in the womb, more and better-organized brain has gone with more and better-organized consciousness. Nor can you get over the fact that when (as a result, it may well be, of the Jury’s verdict) your brainwaves flatten out and cease, so will the consciousness they are giving rise to.

MYSELF: Counsel will never get the hang of what I’m saying as long as he confuses and lumps together Consciousness and what it’s conscious of, Container and its contents, Subject and its objects. Why can’t he understand that he’s taking awareness of things, and making another thing it?

I assure the court that I

don’t

want to wriggle out of the fact that the contents of this Container-which-I-am vary all the way from the subatomic, through the human to the supergalactic, and are in flux all the time. Oh, no, I want to wriggle into it. I revel in all this delightful mutability. But even more do I revel in the fact that the Container Consciousness itself stays forever the same throughout all these developments and deteriorations, all the comings and goings of its contents. Take my own case, and refer again to our Diagram No.8. When I was (in your reckoning) minus nine months old and a single cell in the womb, I was What I am now: to wit, the same Consciousness (x), viewed from region (f), from the place where I then read (and still read, if you come near enough) as cellular. Also, when I shall (again in your reckoning) die and revert to inorganic matter, I shall still be this same Consciousness (x), viewed from region (g), from the place where I shall then read (and already read if you come that near) as molecular. Throughout these and all the other countless views of Me near and far, I remain the unvarying Container, the Viewing and the Viewed One, the Central Reality of which all creatures are at once contents and regional appearances. Theophanies, every one. Appearances of God. Myself, heavily disguised.