The True Meaning of Smekday (3 page)

“I can to fixing your car. I seen it is the broken.”

I folded my arms. “What would a Boov know about fixing cars?”

He huffed. “I am Chief Maintenance Officer Boov. I can to fix everything! I can surely to fix primitive humanscar.”

I didn’t like that crack about my car, but it did need fixing.

“How do I know you’ll do anything? You’ll probably just call your friends and cart me off to Florida.”

The Boov furrowed what might have been his forehead. “Do not you

want

to go to Florida? Is where your people is to be.

All

humans decide to move on to Florida.”

“Hey! I don’t think

we

got to decide anything,” I said.

“Yes!” the Boov answered. “Florida!”

I sighed and paced the aisle. When I looked back at the freezer case, I saw the Boov had picked up my cell phone.

“I could talk to them,” he said gravely. “I could call to them right now.”

It was true. He could.

I slid the broom handle free of the door and opened it. The Boov lunged forward, and I instantly regretted everything, except then I realized he wasn’t attacking me. It must have been a hug, because I can’t think of any better word for it.

“See?” he said. “Boov and humanskind can be friend. I always say!”

I patted him gingerly.

It sounds crazy, I know that, but suddenly I was searching the little town for supplies while the Boov worked on my car. I don’t think I have to say at this point that Pig stayed with him.

I hit five abandoned stores and found crackers, diet milk shakes, bottled water, really hard bagels, Honey Frosted Snox, tomato paste, dry pasta, a bucket of something called TUB! that came with its own spoon, and Lite Choconilla Froot Bites, which broke my usual rule against eating anything that was misspelled. The Boov had told me some things he liked, so I also carried a basket of breath mints, cornstarch, yeast, bouillon cubes, mint dental floss, and typing paper.

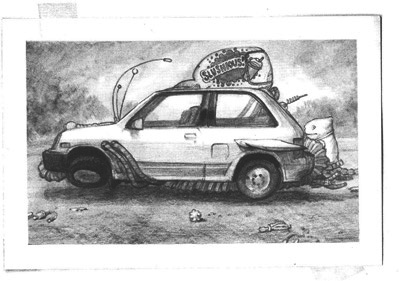

“Hey, Boov!” I shouted on my return. I could see him under the car, banging away. The car, I should mention, now sported three extra antennas. The holes in the windows were somehow not there anymore. There were tubes and hoses connecting certain parts of the car to certain other parts of the car, and a few of what I can only describe as fins. These appeared to be made from metal the Boov had salvaged from the convenience store. One of them showed a picture of a frozen drink and the word “Slushious.”

There was an open toolbox, and the tools were everywhere, all of them strange.

“This seems like an awful lot of trouble for one flat tire,” I said.

The Boov stuck out his head.

“Flat tire?”

I stared back blankly for a second, then walked around to the other side. The tire was still flat.

“The car, it should to hover much better now!” he called happily.

“Hover?” I answered. “Hover

better

? It didn’t hover at

all

before!”

“Hm,” the Boov said, looking down. “So

this

is why the wheels are so dirty.”

“Probably.”

“Sooo, it did to roll?”

“Yes,” I said crisply. “It rolled. On the ground.”

The Boov thought about this for a long few seconds.

“But…how did it to roll with this flat tire?”

I dropped the basket and sat down. “It doesn’t matter,” I said.

“Well,” the Boov replied. “It will to hover wicked good now. I used parts fromto my own vehicle.”

He startled me at this point, the way he said “wicked.” It was slang. Something I didn’t expect him to use. And it wasn’t even popular slang. Nobody said it anymore. Nobody but my mom, and sometimes me. I guess it made me think of Mom, and I guess it made me a little angry.

“Eat your dental floss, Boov,” I said, and kicked him the basket. He seemed to think nothing of it, and did as I said, sucking up strings of floss like spaghetti.

“You do not to say it right,” he said finally.

“Say what?”

“‘Boov.’ The way you says it, it is too short. You must to draw it out, like as a long breath. ‘Bo-o-ov.’”

After a moment I swallowed my anger and gave it a try.

“Booov.”

“No. Bo-o-ov.”

“Bo-o-o-o-ov.”

The Boov frowned. “Now you sound like sheep.”

I shook my head. “Fine. So what’s your name? I’ll call you that.”

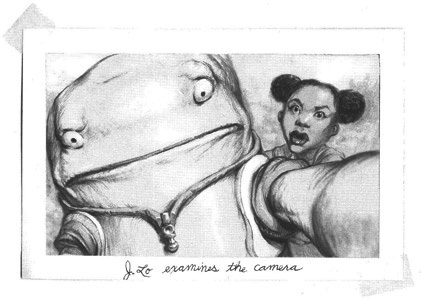

“Ah, no,” the Boov replied. “For humansgirl to correctly be pronouncing my name, you would need two heads. But, as a human name, I have to chosen ‘J.Lo.’”

I stifled a laugh. “J.Lo? Your Earth name is J.Lo?”

“Ah-ah,” J.Lo corrected. “Not ‘Earth.’ ‘Smekland.’”

“What do you mean, ‘Smekland’?”

“That is the thing what we have named this planet. Smekland. As to tribute to our glorious leader, Captain Smek.”

“Wait.” I shook my head. “Whoa. You can’t just rename the planet.”

“Peoples who discover places gets to name it.”

“But it’s

called

Earth. It’s

always

been called Earth.”

J.Lo smiled condescendingly. I wanted to hit him.

“You humans live too much in the pasttime. We did land onto Smekland a long time ago.”

“You landed last Christmas!”

“Ah-ah. Not ‘Christmas.’ ‘Smekday.’”

“Smekday?”

“Smekday.”

So anyway, that was how I learned the true meaning of Smekday. This Boov named J.Lo told me. The Boov didn’t like us celebrating our holidays, so they replaced them all with new ones. Christmas was renamed after Captain Smek, their leader, who had discovered a New World for the Boov, which was Earth. I mean Smekland.

Whatever. The End.

Gratuity—

Interesting style overall, but I’m afraid you didn’t really fulfill the assignment. When the judges from the National Time Capsule Committee read our stories, they’ll be looking for what Smekday means to us, not to the aliens. Remember: the capsule will be dug up a hundred years from now, and the people of the future won’t know what it was like to live during the invasion. If your essay wins the contest, they’ll be reading it to find that out.

Perhaps if you began before the Boov came? There is still some time to rework your composition before the contest entries need to be sent. If you’d like to try again, I’ll consider it for extra credit.

Grade: C+

Gratuity Tucci

Daniel Landry Middle School

8th Grade

THE TRUE MEANING OF SMEKDAY

PART 2:

-or-

How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Boov

Okay. Starting before the Boov came.

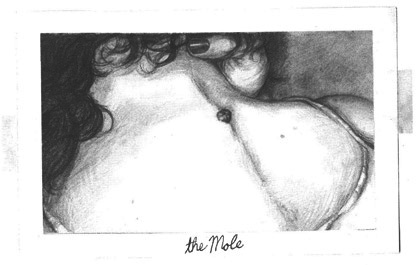

I guess I really need to begin almost two years ago. This was when my mom got the mole on her neck. This was when she was abducted.

I didn’t see it happen, naturally. That’s how it is with these things. Nobody ever gets abducted at a football game, or at church, or right after Kevin Frompky knocks all your books out of your hands between classes and everybody’s looking and laughing and you have no choice but to sock him in the eye.

Or whatever.

No, people always get abducted while they’re driving on empty highways late at night, or from their bedrooms while they’re sleeping, and they’re returned before anyone knows they’re gone. I know this; I’ve checked.

That’s how it was for Mom. She burst into my room one morning, wild-eyed, hair a fright, and told me to look at her neck.

I blinked away sleep and stared where she pointed. I did this without question, because it had only been days since she’d woken me to say that Tom Jones was on the morning show, or that the paper had a “wicked good coupon” for dress shields.

“What am I looking at?” I said blearily.

“The mole,” Mom said. “The

mole

!”

I looked. There was certainly a mole, brown and wrinkly, like a bubble on a pizza. It was right in the middle of the neck, on her backbone.

“’Sfantastic,” I said, yawning. “Good mole.”

“You don’t understand,” Mom said, turning; and the look in her eye made me wake up a little. “It was put there! Last night!”

I blinked a couple of times.

“By the aliens!”

she finished frantically.

I was so awake now. I looked closer. I poked it with my finger.

“I don’t think you’re supposed to touch it,” Mom said quickly, and jerked away. “I feel really veryvery strongly that you shouldn’t touch it.”

There was something strange about Mom’s voice just then. Something kind of flat and dull. “Okay,” I said. “Sorry.

“So…what do you mean ‘aliens’?”

Mom got up and walked around the room. Her voice sounded normal now, if not a little overwrought. She explained that they woke her up last night, two of them, and gave her a shot of something in the arm. She showed me, and there was definitely some kind of red dot on the inside of her right elbow. She knew they’d taken her outside, but she’d drifted off to sleep for a minute, and woke up in a large, shimmering room.

“Wait a minute,” I said. “You fell asleep? How could you fall asleep in the middle of this?”

“I don’t know,” Mom answered, shaking her head. “I wasn’t afraid, Turtlebear. I just wasn’t. I was full of calm.”

I had my own ideas about what she was full of, but I kept them to myself.

Mom went on to explain that the aliens, a lot of them now, had brought her aboard their ship to fold some laundry. They related, not with words but with complicated hand gestures, that they were really impressed with her laundry folding skills. She was guided to a table piled with bright, rubbery suits with tiny sleeves and too many legs. So she got to work. As she folded, she happened to notice another human, a Hispanic man, she said, far off at the other end of the room. They had him opening pickle jars. She thought she ought to say something, say hello, but there was so much folding to do, and then suddenly she felt a hot pain on the back of her neck, and she blacked out. When she woke it was morning.

“They put it on my neck. With some kind of mole gun,” Mom said, nodding to herself.

“But…why?” I asked. “Why would a race of…of intelligent beings travel across the galaxy just to give people moles?”

Mom looked a little hurt. “

I

don’t know. How should

I

know? But it wasn’t there yesterday! You have to admit it wasn’t there yesterday.”

I looked at it, trying to remember. But who remembers a mole?

“Oh, Turtlebear, you believe me, don’t you?”

Let me tell you what I didn’t say. I didn’t say it was all a bad dream. I didn’t say she’s been working too hard and eating too much cheese right before bed. I didn’t tell her for the fiftieth time that I wished she didn’t take those pills to help her sleep.

What I did say was I believed her, because that was how things worked in our house. When she’d return from the grocer’s where she worked with a bundle of spoiled meat she’d saved from the Dumpster, I’d tell her it looked delicious. Then I’d throw it away. When I’d get home from school and find she’d blown our savings on an eight-hundred-dollar vacuum she’d bought from a door-to-door salesman, I’d tell her how great it was. Then I’d get on the phone and get our money back. I said I believed her about the aliens.

“Thank you, Turtlebear. Sweet girl,” she said, hugging me tight. “I knew you would.”

Maybe I should explain about the whole “Turtlebear” thing. It’s a family nickname, apparently, going way back. My birth certificate says “Gratuity Tucci,” but Mom’s called me Turtlebear ever since she learned that “gratuity” didn’t mean what she thought it did. My friends call me Tip.

I guess I’m telling you all this as a way of explaining about my mom. When people ask me about her, I say she’s very pretty. When they ask if she’s smart like me, I say she’s very pretty.

“Sweet girl,” Mom whispered, rocking back and forth. I hugged her back, my face inches from that mole.

There are companies that claim to make a greeting card for every occasion. If any of them are reading this, I couldn’t find a “Sorry all your friends deserted you after your alien abduction” card when I needed one.

And poor Mom, she just couldn’t keep her mouth shut. She told everyone at the grocery store about the whole thing. Even the laundry folding.

Especially

the laundry folding, like it was a really important detail. I wonder now if the aliens didn’t do things like that on purpose, to make abductees sound more crazy.

I was kidnapped by aliens and they made me fold laundry.

I was abducted and the aliens made me clean their rain gutters.

You see what I mean?

So people stopped talking to her. Mom and the other ladies at the store usually went out together on Wednesdays for enormous margaritas served in ceramic sombreros. But one by one they made their excuses, and Mom suddenly had her Wednesdays free. One week she made me her spy, and I crept outside the Wall Street Taco Exchange and peeped through the windows. Sure enough, the grocery store ladies were there, swilling out of Mexican hats and laughing together. And I swear I could tell they were laughing about Mom.

“Were they there?” she asked when I returned to the car. “You didn’t see them, right?”

I slumped in my seat. “Right,” I said.

It was another Wednesday, actually, when I noticed that the mole had changed. I know it was a Wednesday because it was Brownies-and-Movies-Wherein-Guys-Take-Their-Shirts-Off Night, which had replaced Margarita Night when it became clear that the grocery ladies would either have evening dentist appointments or unexplained family emergencies every Wednesday from now until the End of the World.

The End of the World, of course, was only a few months away at this point. Even so that’s still a lot of dentist appointments.

Anyway.

So the brownies were made, and the leading man had just removed his shirt to go swimming, and I was playing with Mom’s hair when I saw it. The mole. It was easily twice as large, and a weird sort of purply color.

I held my breath. “When…did this happen?” I asked.

“Hmm?”

“When did it get…like this?”

Mom turned her head to look at me. “When did what get like what, Turtlebear?”

“Your mole. It’s bigger,” I said, and I pressed my fingertip into it.

Mom shot up from the floor, her face all tight and pinched.

“You shouldn’t touch it,” she said flatly. “It’s not a toy.”

I was a little offended. “I

know

it’s not a toy. Of course it isn’t. It’s gross. Who would want a gross toy? Well, maybe boys would, but that’s none of

my

business—”

“Just don’t touch it,” Mom snapped, and tore off into the kitchen. And this is when, as she was walking away, I saw the mole

glow.

Just for a second. It was bright red, like a Christmas light.

“Whoa!” I shouted after her. “Wait a minute!” I ran into the kitchen, and Mom turned to meet me.

“It’s okay, baby,” she said. “I’m not really mad, I just—”

“Shut up!” I said. “I have to tell you—”

“Don’t you tell me to shut up. YOU shut up.”

“Mom—”

“I don’t like this behavior. You’re acting very weird…ly. Weirdly. Is it weird or weirdly?”

“Mom, you have got to get that mole removed,” I said.

“What? Why?” she said, looking confused. “What?”

“It’s bigger than before, and it’s changed color,” I said. “Moles that change size and color, that’s like, a sure sign of cancer.”

Mom began vigorously shaking her head. “I’m not going to let some quack hack me to pieces,” she said.

“But a second ago

I

saw it glow

!”

There was a heavy silence in the kitchen. Mom looked at me like I had feet growing out of my head.

“Glowing moles are definitely cancerous,” I added. I was pretty sure this was a lie, but I hate losing arguments.

Mom hesitated. Then she reached up to her spine and touched the mole gingerly. She didn’t like what she found, I guess, because her hand snapped back and she began to shake her head again, violently, like she had swimmer’s ear. Like she was trying to shake a thought right out of her.

“I’m the grown-up, and you’re the baby,” she said finally, and left the kitchen. It was how a lot of our fights ended. Not this time.

“We can’t just ignore this,” I said slowly, sweetly. “We have to be brave and go to the doctor. Do you remember Dr. Phillips? You thought he was going to be scary, but everything turned out all—”

“Jesus, Gratuity, stop talking to me like that,” said Mom, shooing me away. “This’ll work itself out.”

I huffed. “Oh,

yeah.

What, like everything else does around here? Yeah, everything else works out, and you never have to worry or think about it or do a thing. But you know why this is different? Because

I can’t fix it this time

!”

“Oh, Gra—Turtlebear, don’t—”

“I need you to cooperate because

I’m

not a doctor yet, and I can’t take

your

mole to have it looked at without

you

attached to it, so I need you to just do as I say!”

Mom just stood there in a door frame for a really long time looking angry, then something like sad, then angry again.

“We’ll talk in the morning!” she said, and slammed the door. Only, our doors were cheap and lightweight and about as good to slam as a Wiffle ball is to hit.

“Mom…” I sighed. “Mom, you’re—”

The door opened again, and she brushed past me to the other end of the hall.

“I knew it was your room,” she mumbled.

The Shirtless Man Movie had clearly been ruined, so we both went to bed early. But I awoke three hours later on account of the twelve glasses of water I’d had before bed. After a few minutes I was seated at the computer.

I turned it on. I forgot that ours was one of those computers that makes a sound like a choir saying “Ahh” when you turn it on.

“Shh,” I hissed, pressing my hands over the speakers. “Stupid computer.”

I peeked out into the hall. Lights off, no sounds. I settled back into my chair and started the web browser, and went to Doc.Com, one of those medical websites. It loaded a cover story about whooping cough, and a banner ad that suggested I ask my doctor if Chubusil was right for me, and then finally the part where I could enter Mom’s symptoms. I typed:

mole changes size color

After a moment, I added:

glows

and hit

RETURN

.

The search turned up something like 140 articles, with names like “Do I Have Cancer?” and “Oh, No! Cancer?” and “Okay, So It’s Cancer, Now What?”

Excited, I clicked on the best match and began to read. Maybe moles

do

glow, I thought. But the first item didn’t mention it. Neither did the second. I read five articles before realizing my search had only turned up results for the words mole, changes, size, and color, except for one that mentioned getting a “healthy glow” in an essay about tanning salons. No mention of glowing moles.

You know that part in the story where the character thinks,

I bet I didn’t really see a ghost after all. I bet it was just a sheet. Wearing chains. Floating through our pantry. Shrieking. I bet it was just my imagination.

You know how you always kind of hate characters who think that? You hate them, and you know you’d never be so stupid not to know a ghost when you saw one, especially when the title of your story is

The Shrieking Specter,

for God’s sake, pardon my language.

This is that part of the story.

You see, the problem is, you don’t

know

you’re in a story. You think you’re just some kid. And you don’t want to believe in the mole, or the ghost, or whatever it is when it’s your turn.