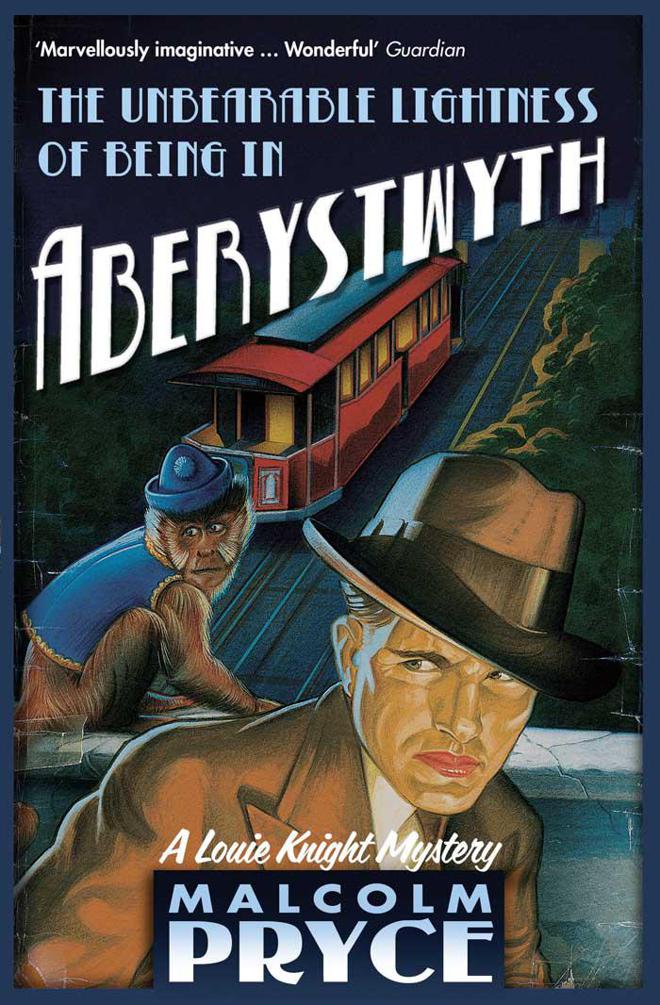

The Unbearable Lightness of Being in Aberystwyth

Read The Unbearable Lightness of Being in Aberystwyth Online

Authors: Malcolm Pryce

To all those who were there during the Jasper House years

Let the lamp affix its beam

The only emperor is the emperor of ice cream.

Wallace Stevens

Praise for

The Unbearable Lightness of Being in Aberystwyth

:

‘This is the third in Pryce’s series of Welsh-set, ironic black comedies packed with witty and original writing … Everyday life takes on extreme and absurd qualities, yet the bit of truth is never far from the surface … The quality of writing is to be relished on every page’

Irish Times

‘A baroque plot sees Knight struggling to find his missing girlfriend, who vanished after eating drugged raspberry ripple, while also trying to solve a 100-year-old mystery for an organ grinder and his monkey. Pryce has a talent for eerie, evocative prose’

Independent on Sunday

‘Welcome to Malcolm Pryce’s Aberystwyth, where the only preparation for reading is to expect the unexpected … this latest novel offers a deeper delve into the devilish imagination of this extraordinary writer. Sharpening the picture with every page, Pryce creates an Aberystwyth in which nothing is what it seems and even the nuns could be out to get you. A master of dry delivery he has an impressive ability to transpose the ordinary with the extraordinary, sweeping you away into a funfair mirror world of grotesque characters and absurd situations which keep you glued to the page at every turn. Inventive, funny and dark, Pryce packs more style into a sentence than most authors could hope for in volumes’

Big Issue

‘Pryce’s Aberystwyth is populated by the same hoods, crooks, heavies, conmen, liars, informers, dealers and bureaucrats that prop up the street corners of Raymond Chandler’s LA, Louie himself possessing the same unshakable idealism and acid tongue as Philip Marlowe. With a droll aphorism or astute observation never more than a sentence away, it’s the vivid characters which make Pryce’s world so intriguing’

Time Out

On the day Dai Brainbocs arrived in Shrewsbury prison, Frankie Mephisto sent for him and explained the situation. He told him they didn’t like bookworms and eggheads in prison and that without protection the frail schoolboy genius would be dead within months. And Frankie was the only man who could provide the necessary protection. That’s when he made the offer. He told Brainbocs he had one dream left in life, and that was to visit Aberystwyth before he died and hear Myfanwy sing at the Bandstand. But, as everyone knew, Myfanwy was dying and would never sing again. You must make her well, he said. You will be put in a cell at the top of the tower overlooking the railway station. You will not be disturbed. But neither, in accordance with a paradigm established by Rumpelstiltskin, will you be allowed to leave the cell until you have found a cure. Whatever books or scientific equipment you require will be made available.

Brainbocs accepted the proposal. He said the offer of scientific equipment would not at that stage be necessary. It was his opinion that in the matter of probing the ineffable mysteries of life, disease and death there existed no finer scientific measuring scope than a gentleman at stool. And so he ordered a new chamber pot – size seven – and went to his tower.

‘HEY MISTER, wanna buy my sister?’

I stopped and turned. The kid was about twelve or thirteen years old and standing next to a discarded lobster pot, a tray of postcards slung from his neck. There were no shoes on his feet and his patched-up trousers stopped four inches below his knee in a comic zigzag hem. The sort of zigzag that never arises from wear and tear and must have been put there by his mum to elicit pity from the bank holiday tourists. Fat chance of that. He could have been standing there on fire and they wouldn’t have cared.

‘I’ll give you a special price. Wanna buy? She’s pretty.’

‘How do you get the boot polish off your cheeks when you go home at night?’

‘Who says it’s boot polish?’

‘It sure isn’t the sort of grime you get from honest toil. Or are they shooting a Dickens movie in Aberystwyth today?’

‘Never mock a man for being poor, mister. What are you looking for anyway? Maybe I can supply it.’

‘What makes you think I’m looking for something?’

‘In my experience there are only two reasons a man comes down the harbour wearing a face like yours. To throw himself in or because he’s looking for something he shouldn’t be looking for.’

‘I could do with a few clients.’

‘Me too. The time is out of joint, Jack. Here, take my card.’

It said, ‘Dewi Poxcrop. Facilitator. Reasonable rates. Discretion assured.’

I put a fifty-pence piece on top of the card tray and moved away. He placed his grimy hand on the cuff of my coat.

‘Are you sure I can’t interest you in my sister?’

‘Sorry, son,’ I said as I pulled free, ‘there’s nothing lonelier than the bought smile of a harlot.’

He stood still for a while and stared at me as I trudged down the avenue of lobster pots drying in the sun. And then he shouted just as I reached the main road, ‘Wash your mouth out, Mac, that’s my sister you’re talking about.’

During my years as Aberystwyth’s only private eye the client’s chair had seen just about every type of backside there was. Fat ones and bony ones; proud ones and pious; some clenched tightly in fear and others trembling with anger; some hot with indignation and some cold with hate. But only one had a tail.

She was a small monkey, and very old, with fur turning white around the muzzle and deep sad dark eyes, like two wishing wells that hadn’t seen a penny in years. She wore an airmail-blue waistcoat and a collarless grandpa shirt with dark rims of grime around the collar and cuffs – the sort of ill-kempt appearance that you get when you have been sleeping rough for a few days, and these are the first days. Inside the collar, loosely knotted into the fur of her throat, was an Ardwyn school tie. She jumped nervously as I walked in the room and flinched a few more times at the banging sounds coming from the kitchenette. I was no zoologist, but she looked like one scared old monkey to me.

I said good morning but she didn’t answer, just watched me closely and followed me round the room with her eyes. I took off my hat and coat and placed them with more than the usual amount of care on the hat stand. Entertaining monkeys was a new one on me but in one respect, at least, I was pretty sure they didn’t differ greatly from the other women of Aberystwyth and so I walked into the kitchen to put the kettle on. My partner, Calamity Jane, was already there, packing my belongings with

an exuberance that accounted for the bangs I’d heard as I arrived. The noises made me flinch in sympathy with the ape who I sensed was still being spooked in the room next door.

I tousled Calamity’s hair in a good morning sort of greeting and said with as little surprise as I could muster, ‘We’ve got a monkey sitting on the client’s chair.’

‘Yeah, I saw that.’ She carried on packing. Normally, you are supposed to wrap the crockery in newspaper but Calamity was putting it straight into a box.

‘It’s quite unusual, isn’t it?’ I said.

‘Uh-huh.’

‘You don’t have to be so cool about it,’ I said.

When the kettle boiled I put teapot, cups, sugar and milk on to a tray and walked back into the office.

When she saw me walking in with the tray, the monkey curled the fingers of her right hand as if holding an invisible mug and then moved it up and down in front of her mouth. I nodded in encouragement. I wouldn’t go so far as to say she smiled – she was a capuchin monkey and they generally keep their cards close to their chest – but a look of heightened interest was evident. She changed position and made a squeaking sound because she was sitting on top of a pile of bubblewrap that had been left on the chair. The few other sticks of furniture I possessed were due to be wrapped in newspaper but the client’s chair, as source of all our income, was a totem that demanded a special reverence. We didn’t have any Gainsboroughs but we had the client’s chair. Although you could say that since we were moving because it had failed to perform the duties of a client’s chair it was a moot point whether it deserved to be propitiated like that.

I poured the tea. The phone rang and I sat down in the chair facing our visitor. Lying on the desk in front of me was the application form for the private detective’s provisional licence from the Bureau in Swansea. Calamity would soon be eighteen and was keen to get her badge: a big bright metal buzzer that she

could stick in her wallet and flick out under the noses of the Aberystwyth villains. If that didn’t frighten them she could always go and buy one of those plastic pin-on sheriff stars from Woolworths. They were equally effective.

I pushed the papers aside, drew the phone over and picked up the receiver.

The voice on the other end had that Chicago-Welsh hybrid that the small-time hoodlums had perfected in this town: ‘What did the monkey say?’

‘What monkey?’

‘Don’t get cute. What did she say?’

‘That information is protected by client privilege.’

‘That’s good, that’s very good, just tell that to Frankie and see where it gets you. When Eli arrives tell him Frankie Mephisto says don’t forget about the book, the one Frankie Mephisto read from cover to cover and threw away because it was bollocks.’