The Uncomfortable Dead

Read The Uncomfortable Dead Online

Authors: Ii Paco Ignacio Taibo,Subcomandante Marcos

Tags: #Suspense, #ebook

Critical Praise for

The Uncomfortable Dead

“A chapter or two into this novel, the reader is likely to put it down, in a mix of puzzlement and wonder, and start thinking. And somewhere—perched on a rooftop in Mexico City surveying the sea of antennas, perhaps, or among the bedraggled, chicken-run villages of Chiapas—the novel’s authors will applaud … The novel is cowritten by Zapatista guerrilla leader Subcomandante Marcos, who has been known to travel on a black motorbike in the company of a deformed chicken he calls ‘the penguin’ as mascot and as symbol of the disenfranchised populations he represents; and by Taibo, Mexican literature’s—actually world literature’s—premier wild man. Great writers by definition are outriders, raiders of a sort, sweeping down from wilderness territories to disturb the peace, overrun the status quo and throw into question everything we know to be true. In book after book—literary novels, revisionist history, collections of journalism, fictionalized biographies, political essays and detective stories—Taibo has done just that … On its face, the novel is a murder mystery, and at the book’s heart, always, is a deep love of Mexico and its people.”

—

James Sallis, Los Angeles Times Book Review

“The authors have wildly different styles: Marcos writes like Dashiell Hammett filtered through the Marx Brothers; Taibo, as in his other novels featuring Belascoarán, is linear and elegantly ironic. This lively crime noir presents a very sad picture of present-day Mexico. Recommended for most collections.”

—

Library Journal

“The Uncomfortable Dead

is a fitting metaphysical detective story from an outpost of the world’s first postmodern revolution. Written in alternating chapters by Zapatista spokesman Subcomandante Marcos and crime writer Paco Ignacio Taibo II, this is a surreal and surpassingly sincere noir … Marcos’ surprising literary voice is reminiscent of Richard Brautigan’s, in that Marcos, too, causes us to look with childlike wonder at a world we thought we knew. This is a powerful tool in a novel that places its focus squarely on governmental abuse, greed and persecution … Marcos’ tone is playful, and Taibo plays along … The book is filled with tangential impressionistic sketches and wildly comic characters that often serve to interrupt the narrative. But there is pleasure in the tangents, chiefly because they afford us an empathetic glimpse of Mexico’s unheralded multitudes. Both Marcos and Taibo take pains to demonstrate that good is as pervasive, if elusive, a force as evil.

The Uncomfortable Dead

is unquestionably on the side of good.”

—

El Paso Times

“Original, funny, biting, and sincere,

The Uncomfortable Dead

is

Huckleberry Finn

by Thomas Pynchon.”

—

Tim McLoughlin, editor of

Brooklyn Noir

“This isn’t your ordinary left-wing noir satire cowritten by Mexico’s most famous crime novelist and the world’s best-known revolutionary leader—it’s a singular event in world literature.”

—

Neal Pollack, author of Never Mind

the Pollacks

“It

doesn’t get much more delicious than this: the mythic, surreal Subcomandante Marcos and the wonderfully ironic Paco Taibo playing duet on a most unexpected story—a noir! But their collaboration is not just any noir—this one’s tender, funny, sly, political, smart, and just plain fun!”

—

Achy Obejas, author of Ruins

“Told in alternating chapters, Taibo’s striking collaboration with the charismatic leftist leader known as Subcomandante Marcos is a curious animal, laying forth planks in the Zapatistas’ platform for the rights of indigenous peoples against globalization and privatization with subversive, comic panache. Taibo’s one-eyed detective, Héctor Belascoarán, finds more questions than answers in his ongoing quest to vanquish evil, this time in the shadowy form of one (or more) Morales, who may have killed a ghost now leaving messages on answering machines around Mexico City. The quixotic Marcos’ inspired contribution is Elías Conteras, an ingenuous investigator from Chiapas imbued with the soul of Sancho Panza. Elías’ charming irreverence fits well in the anarchic eclecticism that governs the fictional universe of Taibo, whose fans will hardly be surprised to find a porn actor who looks like Osama Bin Laden tossed in with Pancho Villa, Barney the dinosaur, and Gustav Mahler. As one might expect, the political trumps the personal in this curious mix of crime novel and position paper, but it is just strange enough to attract a cult audience.”

—

Booklist

“Mexican crime writer Taibo and a real-life spokesperson for the Zapatista movement, Subcomandante Marcos, provide alternating chapters for this postmodern comedic mystery about good, evil and modern revolutionary politics … The authors mix mystery with metafiction: characters operate from beyond the grave or chat about the roles they play in the novel, and Marcos writes his fictional self into the story. Literary readers will nod and smile knowingly …”

—

Publishers

Weekly

“A whodunit by … who dat? Apparently, leading a leftist revolution from the jungles of southern Mexico leaves plenty of time for literary pursuits. Zapatista spokesman Subcomandante Marcos has cowritten a noir mystery novel,

The Uncomfortable Dead,

with Spanish crime author Paco Ignacio Taibo II. The story of detectives investigating a government-backed murderer isn’t the masked rebel’s first stab at fiction. In 1999, Marcos, a former professor who travels with a pet rooster, wrote a children’s book,

Story of the Colors.

His new work is an effort to raise awareness of the Zapatistas and cash for charity.”

—

Time Magazine

This is a work of fiction. All names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the authors’ imaginations. Any resemblance to real events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Published by Akashic Books

Originally published in serial form in Spanish in

La Jornada

with the title

Muertos Incomodos (Falta lo que Falta), Novela a Cuatra Manos

©2005, 2010 Paco Ignacio Taibo II

English translation ©2006 Carlos Lopez

Cover design by Pirate Signal International

Author photos by Marina Taibo

ePUB ISBN-13: 978-1-936-07075-6

ISBN-13: 978-1-933354-89-7

Library of Congress Control Number: 2009923184

All rights reserved

Grateful acknowledgment for permission to include the following at the back of this volume: “¡Zapatista! The Phoenix Rises” by Paco I. Taibo II, originally published in

The Nation

magazine on March 28, 1994; and “The Punchcard and the Hourglass,” an interview with Subcomandante Marcos by Gabriel García Márquez and Roberto Pombo, originally published in English translation in the

New Left Review,

New York, May/June 2001.

Akashic Books

PO Box 1456

New York, NY 10009

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter 1: Sometimes It Takes More Than 500 Years

Chapter 3: Which Is a Little Long

Chapter 4: Sheer Forgetfulness Dwells

Chapter 5: Some Pieces of the Puzzle

Chapter 6: Once You’ve Given Up Your Soul…

Chapter 7: And Pancho Villa Was Not a Witness

Chapter 8: A Night with Morales

Chapter 9: The Bad and the Evil

Chapter 10: The Present Disappears

Chapter 11: The Time of Nobody

Chapter 12: And I Live in the Past

Bonus Materials for the 2010 Edition

An Interview with Paco Ignacio Taibo II

The Punch Card and the Hourglass

An Interview with Subcomandante Marcos

The odd-numbered chapters (1, 3, 5, etc.) in this novel were written by Insurgent Subcomandante Marcos and the even-numbered chapters by Paco Ignacio Taibo II.

The authors’ share of the proceeds from this book will be donated to the Mexico-U.S. Solidarity Network, a nongovernmental agency that works to improve relations between Mexico and the United States.

SOMETIMES IT TAKES MORE THAN 500 YEARS

A

nything that takes more than six months is either a pregnancy or not worth the trouble.

That there’s what El Sup told me, and I just looked at him to see if he was joking or what. Cause the thing is, El Sup sometimes mixes things up and jokes with the city folk like he’s talking to us, or he jokes with us like he’s talking to the city folk. And then nobody much understands him, but he don’t really care a whole lot. He just laughs to himself.

But wasn’t that way this time. El Sup wasn’t joking. You could tell from the way he just stared at that pipe while he was trying to get it to catch. He was just staring at that pipe like he was expecting

it

to answer him instead of me.

He told me he was going to send me into the city; that I had to do a couple a things for the struggle and I had to hang around picking up city ways, and then I could do the job. That there was when I asked him how long I had to hang around picking up city ways and he told me six months. So I ask him if he thought six months was enough, and that’s when he said what he said.

El Sup said this after he spent some time talking to a certain Pepe Carvalho, who’d just got into La Realidad with a message from Don Manolo Vázquez Montalbán and asked to see El Sup. Well, that’s what I heard from Max, the guy who got the message first. Now me, I knew Don Manolo well. It was just a few days ago he’d come up to interview El Sup. He’d brought with him a bunch of sausages, which is some kinda meat, in his knapsack. Now, I didn’t rightly know what in hell sausages was, but when I rode out to meet him, I saw how the dogs was all around him going wild and I asked him if he had meat in that there bag and he said he had sausages, but “they’re for Insurgent Subcomandante Marcos,” that’s what he said. And right then I knew he really respected El Sup, cause that was the way he was called by city people who really respected him and liked him a lot. But like I was saying, that’s how I found out what sausages was, cause I asked if he had meat and he said he had sausages, so sausages must be a way they fix meat in the country where Don Manolo’s from.

Don Manolo don’t like to be called “Manolo,” but “Manuel.” That’s what he said when we was on the way to Headquarters. It took us awhile to get there. First, cause Don Manolo didn’t take to horses really well and he was awhile getting into the saddle. And second, cause the horse they got him was a little skittish and didn’t really take to being rode and all, so he kept making for the pasture instead of heading along the road. Since we spent some time getting the horse to go where we wanted him to go, Don Manolo and me got to talking and I think we even became friends. That’s how I found out he don’t like to be called Manolo, but me, you know, all you gotta do is tell me something is “no” for me to go “yes,” and I don’t do it outta being ornery or nothing, no sir, it’s just the way they made me, or that’s the way I am, you know, contrary: Contreras. That’s what El Sup calls me, “Elías Contreras,” but not cause that’s my name. “Elías” is my fighting name, and “Contreras,” well, that’s what El Sup named me cause he said I had to have a fighting last name too, and seeing as how I was so contrary, a last name like Contreras was just right for me.

Now, all of that happened some time before I went to Guadalajara to pick up a mail pouch in the public baths at La Mutualista and met the Chinese guy Fuang Chu. And it was also a long time before I ran into the Investigation Commission guy called Belascoarán over by the Monument to the Revolution, down in Mexico City. Now, I say

Investigation Commission,

but this Belascoarán feller says

detective.

In our Zapatista territories there ain’t no

detectives,

only

Investigation Commissions.

But this Belascoarán says that in Mexico City there ain’t no

Investigation Commissions,

only

detectives.

So I says to each his own. But like I was saying, all this was a lot after El Sup said what he said about the six months. And it was even later that he ran into Magdalena in Mexico City. Oh, that Magdalena honey! But I’ll tell you more about that later … or maybe I won’t, because some wounds just don’t heal even if you talk them out. On the contrary, the more you dress them up in words, the more they bleed.

Anyway, a long time before El Sup told me about the six months, I’d already investigated some things in the Zapatista autonomous rebel municipalities. You have to say

cases,

not

things,

this Belascoarán told me later, and the thing is, he kept riding me because according to him I talk very different, and whenever he felt like it he would go on correcting the way I talked. But me, instead of changing the way I talked, I just went right on … Contreras, you know? And it was from one of them

cases

that we got the name of this chapter in this here book, which, you’re gonna see, is very different.

But let me tell you a little about who I was. Yeah,

was,

cause I’m deceased now. I was in the militia when we went up in arms back in 1994 and I fought with the troops of the First Zapatista Infantry Regiment, under the command of Sup Pedro, when we took Las Margaritas. Hell, I’d be sixty-one now, but I ain’t, cause I’m dead, which means I’m deceased. I first met Sup Marcos back in 1992, when we voted to go to war. Then later I ran into him in 1994 and we were together when the federal troops chased us out in February of 1995. I was with him and Major Moses when they came at us with war tanks and helicopters and special forces and all, and yeah, it was tough, but as you can see, they didn’t get us. We hightailed it, as they say … although we spent a bunch of days hearing the

thwack-thwack-thwack

of them helicopter blades.

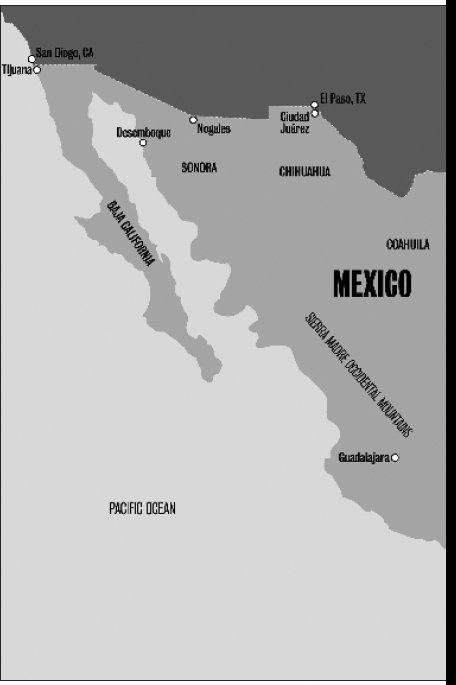

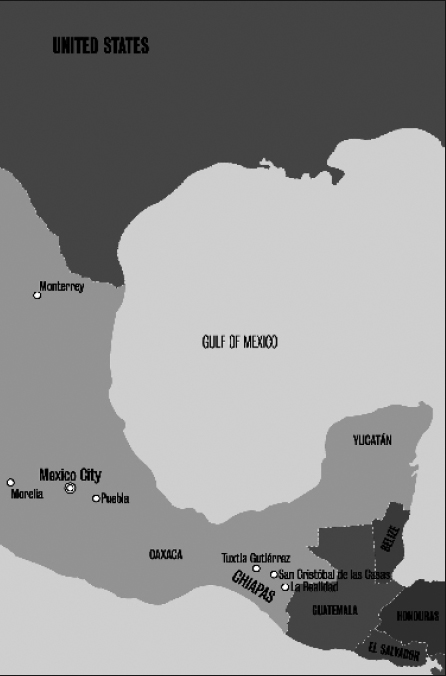

Okay, that’s enough talking. All I wanted to do was introduce myself. I am Elías Contreras and I’m Investigation Commission. But I didn’t used to be Investigation Commission; before I was just a supporter of the Zapatista National Liberation Army over here in Chiapas, which is in our country that’s called Mexico. You wanna know where that is? Well, you can take a look at a map and you’ll find it right over by the …

EZLN General Headquarters

High up on the trunk of a bayalte tree, a lonely toucan polishing his beak. Below, Lieutenant Hilario is checking to see if the horses have finished off the little corn patch, and Insurgent Martina is reviewing the list of state capitals. The guard detail is sitting in front of the little shack cleaning their weapons. On one side, tacked to a pole, the old black flag with the five-pointed star and the letters, EZLN. The star and the letters are a faded red. El Sup steps out of the door. The guards spring to attention.

“Call Lieutenant Colonel José,” says El Sup. José arrives. El Sup hands him some papers. “This just came in.”

After reading the papers, the lieutenant colonel asks, “What are you going to do?”

“I don’t know,” answers El Sup, both of them standing there thinking, as the toucan takes off in a flurry of flapping wings that draws their attention.

After a moment, they look at each other and say in a single voice: “Elías.”

The last rays of sunlight are just fading away when the silhouetted figure of the lieutenant appears riding over the hilltop. He skirts the town, avoiding mud holes and stray glances, until he gets to where Adolfo has his post.

“The major?”

“He’s in a meeting with the municipal authorities.”

The lieutenant goes in to see him.

The major takes the papers and reads.

“Get hold of Elías,” the lieutenant says, “and tell him to drop around he-knows-where to have a chat with the old man, tomorrow, if he can make it; if not, when he gets a chance. That’s all.”

Grabbing the radio, the major barks, “Lama gama. If you copy, tell the big eye to buy his telescope tomorrow, or whenever he can.”

High up on a hill, the operator receives the message and relays, “Lovebird, Lovebird, if you copy, there’s a forty for Elías, and Cloud says he’s to go tomorrow.”

In the town, the man in charge of the post relays to the CO, “They want you to get Elías and have him go to La Realidad tomorrow.”

The sun has long since taken cover behind the rolling hills when Elías shows up at the door of his shack, a bundle of pumpkins hanging from his head sling. In one hand he holds his

chimba,

and in the other …

The Machete

Yeah, El Sup didn’t actually show me the paper, but he told me what it was all about. There was a disappearance. The message said that one of the women had disappeared and that El Sup should write up a paper blaming it on the bad government. Which is actually what El Sup is sposed to do, the problem being that the citizens, that is, the city folk, are already used to the Zapatistas telling them the truth, that is, that we don’t lie to them. So like I said, the problem is that if El Sup writes his communiqué accusing the government and then it turns out that the woman ain’t disappeared at all and the bad government didn’t harm her, what happens is our word begins to look weak, and what happens is people stop believing us. So then, my job was to investigate to see if she really was disappeared or what, and then I was to report to El Sup what it was that happened so he could decide what to do.

I asked El Sup how much time I had and he said I had to do it in three days. I didn’t ask why it was three days and not one, ten, or fifteen. That was for him to know. So I went to saddle up a mule, and that same afternoon I headed out for Entre Cerros, which is what they call the town where they had the disappearance of María—or the former María, cause what if she’s deceased?—who is/was the wife of the local Zapatista rep in that town.

Soon as I got to the town I talked to the rep, whose name is Genaro and who is or was the husband of the deceased María. Well, she ain’t deceased, not yet anyway. That’s what we had to find out. So Genaro told me that she went out for firewood and that later, well, she didn’t come back again. Didya look for her? Yes! Ya didn’t find her? No! He said how if he’d found her he wouldn’t’ve called Headquarters. That was three weeks ago. So why didn’t he call then? Cause there was still a chance she’d turn up. So, did he know which way she headed? No! Maybe she was taken by the Army or the paramilitaries and she was already deceased. Who was going to make his

pozol

and his tortillas? And who was going to take care of the kids?

So I says goodbye to Genaro, thinking how he was more worried about who was going to do his cooking than about the deceased, or not, María, and thinking that what he was remembering was not that he loved her or nothing like that, but all the work she did around the house and all. Then I went down to the stream where the women did the washing and I ran into cousin Eulogia. She was with Heriberto, my godson, and she was washing something. I decided to talk to her cause she was naturally real nosey, and she told me that just before she disappeared, the deceased María, who wasn’t really deceased yet, had quit going to the meetings of the Women for Dignity Cooperative just when they were fixing to name her to the bureau, and that she, Eulogia, had gone to see her, the alleged deceased, to ask why it was that she wasn’t going to the meetings, and that she, María, answered, “Who’s gonna make me?” and didn’t say no more cause just then Genaro showed up and María shut up and just went on grinding corn. I asked if María could have got lost in the woods, and Eulogia went, “How’s she gonna get lost when she knows every path and every trail?”

“So she didn’t get lost,” I says.

“No!” she says.

“So then what?” I says.

“You ask me, I think it was that demon with the hat—

El Sombrerón

—who hauled her away,” she says.

“Shit, cousin, you’re old enough to not be believing those stories about

El Sombrerón.”

“All I know is that things happen, cousin, like what happened to Ruperto’s wife,” Eulogia insisted.

“Ah, c’mon, cousin, that wasn’t no

Sombrerón.

Don’t you remember how they finally found her all cuddled up naked behind the fireplace?”

“That may be,” Eulogia said, “but there’s a whole lot of other

Sombrerón

stories I figure are true enough.”

Well, right then I didn’t have time to explain to cousin Eulogia how those stories about

El Sombrerón

were just that, stories, so I headed for the trail that lead up to where they go for firewood. I was just about leaving the town when I heard a voice behind me: “Is that Elías Contreras?”

And I turned to see who it was, and it was Comandante Tacho, who was just getting into town—to talk up the citizens, I think.

“So how’re you, Tacho?” I said.

I wanted to hang around and chat with him about neoliberalism and globalization and all, but I remembered I only had three days to clear up the matter of the deceased María, so I bid him goodbye.

“I’ll be moving along now,” I said.

“Oh, so you’re on a mission?”

“That’s about it,” I said.

“Go with God then, Don Elías” he said.

“And you, Don Tacho,” I added and hit the trail.

As I was getting to the sunflower fields it started raining. I wasn’t carrying nothing to keep the rain off, so I started hollering and cussing, which don’t keep you dry, but it does warm you up a bit. I followed the firewood trail every which way and back again, cause the thing spreads out like the branches of a tree, but no matter how far I went up any one of them branches, I didn’t find nothing to tell me what could have happened to the alleged deceased María. I went over by the stream and had my

pozol

sitting on a rock. Night falls hard and fast in the woods and although there was a big old moon, I had to use a light to get back to the trail.

So now what?

I asked myself, just staring like a dummy at the branches cut by a machete … machete …

Machete! That’s it! There was no sign of the machete the alleged deceased María had used to cut firewood. And then I remembered that back at Genaro’s I’d seen a machete by one of the piles of firewood stacked up against the side of the shack. There was a goodly amount of wood there, so why would the right now not-so-deceased María have gone out to chop more, seeing as how she already had plenty? And that was when I got to thinking that María had not been disappeared, but had disappeared herself. What I mean is that, like folks around here say, she just up and left.