The United Nations Security Council and War:The Evolution of Thought and Practice since 1945 (12 page)

Authors: Adam Roberts,Vaughan Lowe,Jennifer Welsh,Dominik Zaum

• The control exercised by the General Assembly in making elections to the Council. In many cases this is too tenuous and long-range to amount to much: however, support from their like-minded groups which candidates depend upon in order to get elected carries with it some expectations of future behaviour that might imply a form of control, though whether it would be beneficial is another question entirely.

• The fact that the Council is nowadays called upon to manage and confront crises on a rolling basis, with decision following decision as events develop (i.e. quite different from the Cold War pattern according to which the Council would make an occasional foray, leave behind a resolution, and then retreat). The scope, therefore, is greater for the political reaction to earlier decisions to shape the detail and even direction of later ones. But for that to happen the

Council’s processes have to open themselves to that sort of influence, and its resolutions have to be seen more as policy instruments than tablets of stone.

• The capacity for states to undermine Council resolutions through shoddy compliance and spurious implementation, and through their decisions on the provision or otherwise of contingents for peacekeeping or other forces or bodies. They have also at times illegally withheld payments due to the UN.

Even though the operation of such means of pressure may be chaotic and disruptive, these are critically important constraints on the Council. In formal terms they are not part of a system of accountability, but Council decisions are powerfully influenced by them.

The Security Council has a real, but not great, influence on the development of international law.

82

Its reactions to uses of armed force in situations such as the Middle East wars give it the opportunity to make plain its view of the legality of specificactions and thus to refine the meaning and understanding of concepts such as self-defence. Among the clearest instances were its affirmations in resolutions in September 2001 that it regards ‘any act of international terrorism, as a threat to international peace and security’, and that ‘the inherent right of individual or collective self defence’ exists in relation to terrorist attacks.

83

However, such instances are not the general rule. The Council shows no great enthusiasm for a role as authoritative interpreter of the law, and prefers to concentrate on attempts to agree upon practical steps to address the crisis rather than on pursuit of the delights of debates over doctrine and taxonomy.

Much more significant is the Council’s role in establishing international criminal tribunals, on a variety of models, to deal with allegations of serious crimes committed during the conflicts in the former Yugoslavia, Rwanda, Cambodia, Sierra Leone, and Lebanon.

84

The tribunals do not all have the same form. The Yugoslav and Rwanda tribunals are true international criminal tribunals established by the Council using its

Chapter VII

powers. No state can refuse to recognize these tribunals, and the use of the Council powers gives them as much legitimacy as the international legal system can muster. The other tribunals, in contrast, were not set up by Security Council fiat but by means of agreement negotiated between the UN and the parties.

85

These tribunals, which are hybrid national–international tribunals, may apply

equally high standards of justice, and be equally effective, though they appear to have faced greater challenges to their legitimacy. The move towards the ‘negotiated’ model may signal a desire on the part of the Council to distance itself from the details of conflict management, leaving it with a role focused more on strategy and on support for efforts made by states directly involved.

HANGES IN THE

I

NCIDENCE OF

W

AR SINCE

1945

There have been significant changes in the incidence and character of armed conflict in the UN era, as compared with earlier periods. Arguably, these changes have been influenced by the role of the Security Council; certainly, they have affected its work and even changed its role. In brief summary, four propositions can be advanced about a possible reduction in the incidence and toll of war since 1945:

1. In the period since 1945, and especially since the mid-1970s, the incidence of interstate wars has declined as compared with earlier periods.

2. The death toll from interstate wars is also less than in earlier periods.

3. Colonial wars, as fought by European countries in their overseas possessions, declined dramatically following the demise of the European empires in the period from 1945 to the 1970s.

The decline of international war: Facts and figures4. Since 1945, and especially since the 1970s, a principal form of armed conflict has been civil wars and other conflicts in which at least one of the parties is not, or not yet, a state. In cases where outside powers become directly involved in such wars, they can be described as ‘internationalized civil wars’.

The statistical study of war, on which such propositions depend, is fraught with difficulty. Five problems stand out. First is the notorious difficulty of determining what constitutes a war: whether to include certain forms of political violence that assume a character that is different from interstate war, and whether to view certain distinct campaigns or periods as part of a single war or as separate entities. The second problem is that it is artificial to count each war (however defined) as simply one unit, when wars vary greatly in severity: casualty figures may be a better guide than the mere fact of war. Third is the difficulty of getting accurate information about the number of casualties in a particular conflict. Fourth is the selection of time periods for evaluation:

comparisons between different periods can be misleading. Fifthly, extrapolation from present trends into the future is dangerous. For these and other reasons, various statistical studies of war have come up with some different figures and different conclusions about the incidence, causes, and changing character of war.

However, an impressive number of statistical studies of the incidence of armed conflict support the four propositions that were outlined above.

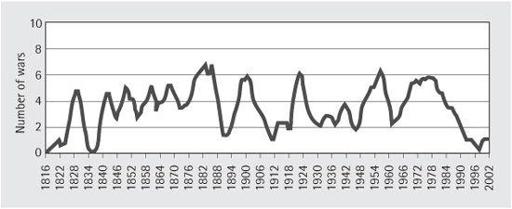

Figures 1.1

and

1.2

, based in part on databases maintained by the Oslo Peace Research Institute and the Uppsala Conflict Data Program, illustrate the decline in the incidence of international wars.

Figure 1.1

, based on statistics indicating that between 1816 and 2002 there were 199 international wars (including wars of colonial conquest and liberation), shows a considerable decline in such wars, which is particularly marked for the period since around 1980.

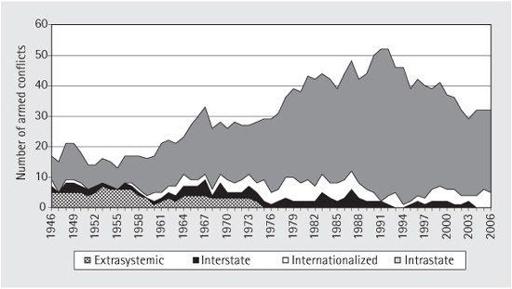

Figure 1.2

shows a decline within the period since 1945 in more detail. It shows four types of armed conflict, as follows:

1.

Extra-systemic armed conflict.

Colonial war between an external army and an indigenous force.

2.

Interstate armed conflict.

War between sovereign states.

3.

Internationalized internal armed conflict.

Civil war in which one side or both receive external support, including the participation of foreign troops.

4.

Internal armed conflict.

Civil war within a state.

As the two figures show, any diminution of war that there has been is far from amounting to its elimination. It may or may not continue: there have been periods before of relatively low levels of interstate war. In any case, there have still been numerous wars since 1945, including many with an international dimension. Nonetheless, as regards the category of interstate armed conflict since the mid-1970s, the diminution appears to be enough of a reality for its causes to be worth investigation. This diminution is especially noteworthy as the number of states has been at an unusually high level in this very period – as indicated by the increase in UN membership from 51 in October 1945 to 192 at the end of 2006.

What are the possible explanations for this claimed decline? The

Human Security Report

for 2005 sets out a series of factors that may account for the diminution in the incidence of war since the 1980s:

• A dramatic increase in the number of democracies. In 1946, there were 20 democracies in the world; in 2005, there were 88. Many scholars argue that this trend has reduced the likelihood of international war because democratic states almost never fight each other.

Fig.1.1 Incidence of international wars 1816–2002 (expressed as a five-year moving average)

Source: Data in Kristian Skrede Gleditsch, ‘A Revised List of Wars Between and Within Independent States, 1816–2002’,

International Interactions

30 (2004), 231–62. This version is based on the table as published in the annual publication of the Human Security Centre of the University of British Columbia,

Human Security Report: War and Peace in the 21st Century

(New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 148.

• An increase in economic interdependence. Greater global economic interdependence has increased the costs of cross-border aggression while significantly reducing its benefits.

• A decline in the economic utility of war. The most effective path to prosperity in modern economies is through increasing productivity and international trade, not through seizing land and raw materials. In addition, the existence of an open global trading regime means it is nearly always cheaper to buy resources from overseas than to use force to acquire them.

Only the very end of the extract mentions the growth in international institutions as a possible explanation for the declining trend: ‘The greatly increased involvement by governments in international institutions can help reduce the incidence of conflict. Such institutions play an important direct role in building global norms that encourage the peaceful settlement of disputes. They can also benefit security indirectly by helping promote democratisation and interdependence.’

86

In addition to the explanations for the decline in interstate war considered by the

Human Security Report

, there are other important possibilities:

• Nuclear weapons. The UN era has coincided with the nuclear age. On 16 July 1945, just three weeks after the signing of the UN Charter, the first test of an atomic bomb took place, at Alamogordo, New Mexico. In 1949 the Soviet Union followed suit. While it involved terrible risks, the incorporation of nuclear weapons into their armouries undoubtedly induced an element of caution in relations between major powers – and also in the policies of some of their allies.

This critically important development overlapped with the role of the UN Security Council – not least because, from 1971 onwards, the five recognized nuclear powers were also the five Permanent Members of the Council. Subsequently, the development of nuclear weapons by Israel, India, Pakistan, North Korea, and others indicated that the vision of the Security Council Permanent Members as forming the club of nuclear responsibles and maintaining a system of nuclear non-proliferation was not working. It appeared that a number of states outside the P5 had little confidence in the UN security system, and preferred to rely on their own means of deterrence.

87

Fig.1.2 Incidence of four types of armed conflicts 1945–2006

Source: data assembled jointly by the International Peace Research Institute in Oslo and the Uppsala Conflict Database. Obtainable at

www.pcr.uu.se/database/index.php

. This graph was published in Lotta Harbom and Peter Wallensteen, ‘Armed Conflict, 1989–2006’,

Journal of Peace Research

, 44, no. 5 (Sep. 2007), 623–34.