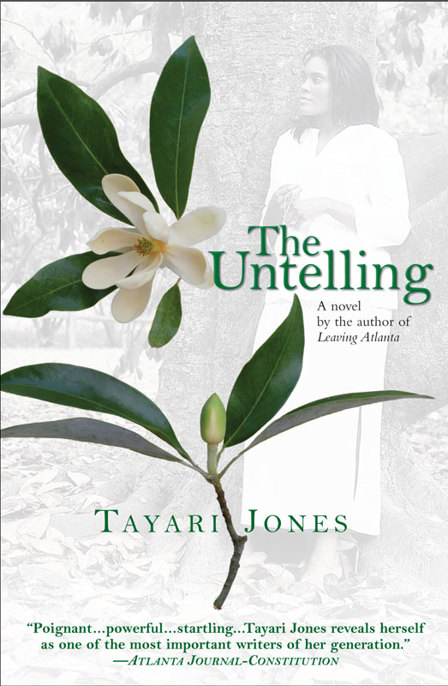

The Untelling

Authors: Tayari Jones

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is coincidental.

Copyright © 2005 by Tayari Jones

All rights reserved.

Warner Books

Hachette Book Group, USA

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our Web site at

www.HachetteBookGroupUSA.com

.

First eBook Edition: April 2005

ISBN: 978-0-446-53399-7

Contents

Leaving Atlanta

this is for doug

My parents and siblings are extremely good people. I am lucky.

Thanks to Sally Keith, who “gets” me, and Bryn “Pie” Chancellor, who scours all drafts. Anne Warner nudges me toward what is right. Camille Dungy is bright as a horn.

Major love to my friends who lent their eyes to any of the six major incarnations of this novel. These folks helped me see what was good but told me how to fix what needed fixing: Barbara Ann Posey Jones, Deanna Bryant, Ginney Fowler, João Costa Vargas, Chad Unrein, Maxine Kennedy, Jafari Allen, David Van Fossen, Kiyana Sakena Horton, John W. Holman, Aisha Moon, June Aldridge, and Eric Beaumont.

Linda Eldridge is everything a bartender should be. Scott Vaughn taught me to relax. Renee Simms helps me understand perspective. Jewell Parker Rhodes, Crystal Wilkinson, Merrill Fietell, Monique Truong, and Suji Kwok Kim are the counterargument to all the snarky things people say about writers. Deirdre McNamer was an inspiration even before we met.

Mr. Ron Carlson helped me at the start of this project; you will find his fingerprints everywhere. Ms. Pearl Cleage is one smart colored woman.

I want to acknowledge the generous assistance of the MacDowell Colony, the Family and Friends of Gerald Freund, the Corporation of Yaddo, John and Joan Jakobson, the LEF Foundation, Arizona Commission on the Arts, the Ledig House International Writers Colony, Le Chateau de Lavigny International Writers Colony, Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, Wesleyan Summer Writers Conference, East Tennessee State University, and the G.E. Foundation.

Jane Dystel is a shrewd agent, loyal advocate, and extremely kind human being. Caryn Karmatz Rudy is my editor and friend.

A

riadne, my given name,

the one that’s on my driver’s license, is the sort of name that you’re supposed to grow into. It was my mother’s idea. Her parents underestimated her when they called her Eloise, a name that had strained at the seams before she was old enough to spell it. Our mother’s gifts to the three of us were lush, extravagant, roomy names. Names that fit us like oversized coats, trimmed in seed pearls, gold braid, and the hides of baby seals. My father had wanted us to have family names, with at least one of us girls named after his mother, Lula. My mother, who indulged my father in many things, could not give him this. Why, she wondered, would someone in this day and age give a child a name that was so

Mississippi

? “That is not what Dr. King died for.”

People shook their heads with each pink birth announcement; teachers squinted at class rolls and said, “Who ever heard of black people with names like that? Those kids are going to be

confused

.”

Mama never forgave us for not appreciating our names. When my older sister, Hermione, came home from first grade and announced that she wanted to be called Sonja, Mama had said, “Why do you have to be so ungrateful? Your name is from

Shakespeare.

” My name, Ariadne, is taken from the Greek. Mama explained that I was named for a princess. My tenth-grade English book gave me the rest of the story. Ariadne was a Greek princess; this much is true—my mother is not the type to lie. The princess Ariadne saved her lover’s life with a length of string which he used to wind his way out of a deadly maze. To show his gratitude, he married her. After only a few weeks he dumped her on a rocky island and sailed off. When I confronted my mother with this story, she insisted that there was a happier ending, that Ariadne ended up marrying the god of wine, but for me the story ends when she is sitting on the island watching the black-sailed boat churn away.

My other sister, the baby, Mama’s miracle child, the one who got born despite the tied tubes, her name was Genevieve, for the patron saint of Paris.

Nicknames were forbidden.

I was there when Daddy said Genevieve was too much name for a baby. Couldn’t we at least call her Jenny? Mama sighed and waved her hand, one of her elegant gestures that let everyone know that she was more than just an Eloise.

I was nine, sitting on the floor between Mama’s knees while she threaded clear plastic beads onto my braids. I felt hot prickles of jealousy over my lip. Why hadn’t Daddy stuck up for me and my name? “Ariadne” was obviously the worst of the lot. Genevieve, who had the best name, a name that someone had at least heard of, she lay on a white receiving blanket and chewed on her toes.

I looked up and met my father’s eyes, and turned my face to the orange carpet before they could accuse me of listening to grown folks’ conversations.

Mama said, “Lincoln, maybe it

is

too much name for a baby. But Genevieve will not be a baby forever.”

I looked up again, fast this time. Mama lost her grip on my braid; heart-shaped beads fell on the floor and rolled under the couch. We were all still for the duration of three heartbeats. This had been one of those Greek myth moments, when you could just hear the gods look up from their newspapers and raise their eyebrows.

On the Saturday before Easter 1978, Genevieve was six months old, teething and blowing spit bubbles, when the whole family piled into our burgundy Buick. I liked her. Hermione often told people that I was jealous of the baby because of her soft hair and bleached pine bedroom set. But I wasn’t jealous. Genevieve was a beautiful thing, all curves and folds of flesh, smelling of rose water and drool. This is what I remember and this is the truth.

We were on our way to the spring performance at the YWCA, where I took ballet, tap, and jazz. The recital was to be held in a large gymnasium that smelled of Pine-Sol and feet, but all of us were dressed up and looking good. Daddy wore a white shirt with “creases sharp enough to shave with,” he’d said, running his fingers down his stiff sleeve. According to Mama, Hermione’s pants were too tight, but they looked good; on her the snugness seemed deliberate, a taunt. My mother outdressed us all, but that was her way. She wore a butter-colored suit and matching pumps. Genevieve was just a little brown face in a nest of aquamarine lace and ruffles. I’d put on a green jumper over my pink leotard and white tights. This was my favorite dress, worn at least once a week, pulled hot from the dryer each time. I liked it because it covered the raised outline of my training bra, the first of anyone in beginning tap dance. When I wore it, I seemed to be like any other girl with my tight plaits and heart-shaped beads.

Hermione hadn’t wanted to go. She was almost fifteen and would have rather stayed home alone, staring at the phone and wondering why boys didn’t call her. It was because she was fat. I knew this because I had read her red clothbound diary.

Must lose weight

, she had scrawled.

Orthodontia—expensive. Necessary?

I was glad that she was there, even gladder that she hadn’t wanted to be. Staring sullen out of the window, she was making a “sacrifice,” a word we’d talked about last week in Sunday school.

Why hadn’t we taken a photo of ourselves before piling into the car? Just a Polaroid, or a quick snap with Hermione’s 126 camera, creating something that I could use to compare with the images in my head, so that I could be sure exactly what was remembered and what was invented or just wished for.

I scooted closer to Hermione, breathing big gulps of her honeysuckle perfume. I lifted the red velvet cake from her lap. It was a big one, three layers, and dusted on top with chopped pecans. This lovely cake, slightly extravagant, was our family’s contribution to the recital reception.

I was happy. I do remember this.

I had been telling the story of the dogwood trees, raising my voice over Hermione, who sang along with the staticky car radio.

“I’m trying to talk,” I said.

“I’m trying to sing.”

Daddy turned down the radio. Mama bounced Genevieve on her lap and said, “Shh, sweetie,” to the baby and “Go on, honey,” to me.

“Before Jesus,” I told them, projecting from my diaphragm, like my Sunday school teacher had taught me, “the dogwood was as tall and mighty as the oak and pine.”

“Please tell me that’s not your Easter speech,” Hermione said. “You know that’s just a myth, don’t you?”

“You don’t even know what I was going to say. You didn’t let me finish.”

Hermione shrugged her heavy shoulders. “You were about to say that they used the dogwood to make the cross and now the tree is so shamed that it grows all little and hunched up.”

“That’s a good story,” Daddy said. His eyes smiled at me in the rearview mirror.

“And,” I said, “there’s the part about the flowers. On every one of the petals is a little red spot. That’s the blood so nobody could forget about Jesus.”

“Daddy,” Hermione said, “can you turn the radio back up? Did they even

have

dogwood trees where Jesus grew up, in Bethlehem or wherever?”

I know what happened next, although I didn’t see it. My eyes were on the nut-crusted sides of the red velvet cake when a blue El Dorado barreled down the left side of Hunter Street, just after Mosely Park. I’d snuck my finger under the cellophane for a taste of icing and was trying to silently work my thumb to my mouth when Daddy said, “Jesus,” and I thought we were still talking about dogwoods. Then the car lunged to the right, to the left, and back again.

I ruined the cake when our car crumpled against the bark of a hundred-year-old magnolia. I hugged it to me, grinding the white icing and red meat of the cake into the bib of my jumper. When the car stopped moving, I didn’t look up right away. I stared at my lap and the mess I’d made, dark red like watermelon, busted and overripe. Then, Mama wailed and Genevieve stayed quiet. Daddy barked, “Wait!” and Hermione cursed softly, enunciating each filthy word while I stuffed a handful of cake into my mouth, choking on its buttery sweetness.

Then the women came, some streaming, some tumbling, from frame houses built among the dogwoods. They ducked under blooming branches, using the flats of their hands to keep sheer scarves on their heads. They hurried toward me and my family, screaming at children to call the ambulance. These were the sort of women who could stop cars by placing their bodies in the roads. They hustled across the street without looking and the cars did stop. They ran to help us while speaking the name of God.

I watched all of this through the lined rear windshield of the Buick. On the radio the Commodores sang, “I’m easy like Sunday morning.” I wasn’t hurt. Later I bit my finger until it bled, but when the metal bumper connected with the hundred-year-old bark, I was fine. I regarded it all with slight disbelief, like I was watching a movie with bad actors. My mother bolted from the car, holding Genevieve, who was silent and impossibly bent. When Mama sprang from the car, Hermione clambered out behind her. I scooted toward the open car door, but my sister turned. “You stay here with Daddy,” she said, pushing me down onto the ruined cake. I said, “Okay,” mashing the metal plates of my tap shoes into red velvet sludge.

Daddy was slumped but not silent against the leather-covered steering wheel, taking in the stinking air with jagged breaths. I dug old french fries from crevices in the car seat and ate them.

A light-skinned lady wearing pink hair rollers tapped on the window. I cranked it open, letting in a sweet whiff of magnolia and daffodil. She pushed her face into the car, blocking my breeze.

“You all right in there?”

“Yes, ma’am,” I said.

“What about everybody else?”

“I’m stuck,” Daddy grunted. “I’m hurt some.”

“Don’t move, then,” the lady said. “You’re not supposed to move when you’re hurt.”

“I want to get out and see my mama. I got icing on my shoe. The cake got mashed.” I reached down for a handful of oily red cake and held it out to her.

The lady looked at my hands and then turned to where Mama was. “Jesus,” she said. “Go on and stay where you are, sweetheart. Help be here in a minute. Everybody’s tending to your mama. She got your sister there with her. Holler if you need something.”

In the backseat I wiped my hands on my tights and then twisted the button on the pocket of my jumper until it came loose. Then I popped the pearlized plastic in my mouth, chewing with the stale french fries until a pain in my jaw reached my ears and I could almost cry. I wanted to leave the car and escape my father’s groaning, but that would have been the sort of cruelty that could never be forgiven.

“You hurt, Daddy?”

“Yes.”

“Want me to climb up there?”

“No. Stay where you are.”

“But I’m by myself.”

“No, you’re not. I’m here.”

“It’s hot in here.”

“Spring,” he said.

Daddy smelled bad, like sweat and something hotter and thicker. “What about the cake?” he said with words that were more air than voice. I felt something swelling inside me, like what was supposed to happen if you swallowed watermelon seeds. The fruit would grow, crushing you to death from the inside.

“I think I’m going to die,” I told him.

“No, baby. You’re not going to die. Tell me about the cake.”

I looked down at the chunks of moist red cake and off-white icing on the rubber floor mats. “It’s ruined.” I felt my face collapsing. I opened my mouth, but there was no air to cry with.

“Ariadne, baby,” he said. “I’m so sorry.”

He started to sob in gasps and coughs. I stuck my fingers in my ears and sang nursery rhymes. I sang about Georgie Porgie, Mary and her lamb, even nasty rhymes I had heard boys sing at school. With my hands tight over my ears I ignored my father, my good kind father with the space between his front teeth. My sweet daddy who gave me two-dollar bills for every A on my report card. To the only man who had ever loved me I said, “I’m not listening. I can’t hear you.”

Since we had no relatives, the police called Mr. Phinazee, my father’s best friend. He was out of town, so his daughter, Colette, came to pick me up. She was only about nineteen, but she seemed like a woman to me. She wore the white barber’s coat she wore to work at her father’s shop.

“Come out,” she said to me, opening the door.

I scooted to the other side of the car, pressing against the door. My hands were still sweet from cake and I pressed them to my mouth, nicking my skin on the edges of my teeth.

“Come on,” she said, crawling in. A heart-shaped locket bounced at her throat.

She was close to me now. Colette’s face was young, as smooth as cardboard and the same color. Hands around my waist, she tugged me from the canal of the backseat into the spring day.

When the paramedics came to remove my father from the car, she held me to her and used one rough hand to press my face into her collarbone. “Don’t look up,” she said. Her other hand rubbed my back in slow, easy circles. I stiffened, worried that she would feel my bra through the armor of my jumper. But she just rocked me like an infant and hummed a quiet tune.

Many times since then, I’ve tried to identify the song that was on her lips that afternoon. Sometimes I am convinced that she hummed “Amazing Grace” while they strapped my father to the stretcher and hurried him away. But every now and again I will hear a scrap of music that pierces my heart and I will think that maybe this is the song she played in my ear, the song that separated me from my pain for a few moments on the worst day of my life.

“Aria,” she said softly into my hair. “Shh, Aria.”

I knew that she was talking to me, although no one had ever shortened my name.

“I like it when you call me that.”

Aria wasn’t a name that I needed to grow into, something I could appreciate later. It was a name I could use right then, leaning against a police sedan on the side of the road near a hundred-year-old magnolia. I slid into this new name, pulling it close around me like a donated blanket.

“Are my daddy and Genevieve going to die?” I asked Colette.

“That’s up to God,” she said, laying me down on the backseat of her father’s Brougham.