The Vine Basket (20 page)

Authors: Josanne La Valley

So very long ago.

The sounds Ata made on the

rawap

now were filled with grief. Sounds that told what lay in his heart unsaid.

Then a melody began to emerge from the chords. One Mehrigul knew. A song Memet had heard in the cafés in Hotan, and played and sung for them:

Â

When a tree is covered with ripe fruit it bows down

Don't be proud

Those who stand tall and bear no fruit take the fruit of others

Don't be proud

Â

Ata stopped singing. Only his fingers moved, repeating the chord he had stopped on over and over. Creating sounds that wept for him, and with him. Wept for the oppression of his people.

“No, Ata,” Mehrigul said. “We can't let them take from us what is ours. Our soft hearts must not betray our spirits.” She lowered her eyes. Maybe she'd said more than was her place, but she had no urge to take back her words.

“Let's finish the song,” she said.

Ata stopped strumming. “Don't be proud,” Mehrigul whispered. “Don't be proud.”

Finally, Ata nodded. He took a firmer grip on the

rawap.

A different swell of notes soundedâthe lead into the next line.

Â

We live our lives unequal but in the grave all are the same dust . . .

Â

Mehrigul sang along in a quiet voice. If she was given a chance, here in their own land beside the desert in the shadow of the mountains, she would make herself heard.

Uyghur Service Editor, Radio Free Asia

I read

The Vine Basket

with joy and tears. I loved it.

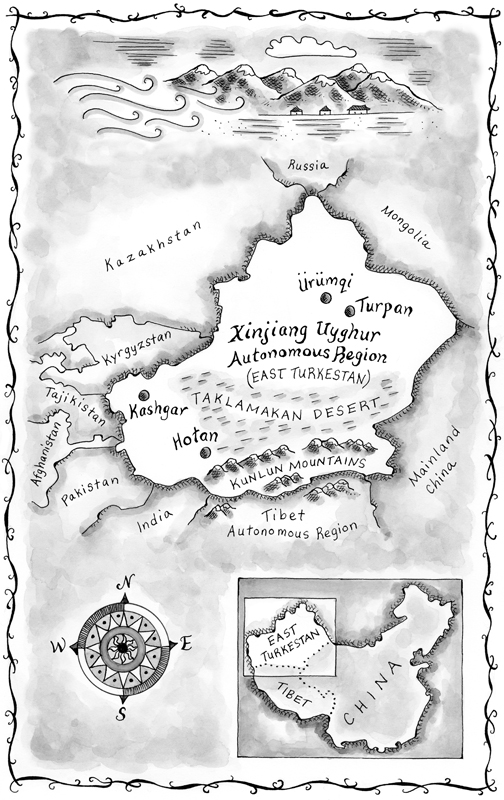

The story takes place in a small community on the edge of the Taklamakan Desert in East Turkestan's (Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region's) Hotan prefecture. I grew up in a similar village. Life was simpler and happier then, when my Uyghur culture was dominant in the region. Still, I was filled with nostalgia when I read this book. I strongly recommend it for those who want to learn about what life is like in the lesser-known parts of China.

The Vine Basket

touches on many aspects of the Uyghur political situation. It describes the experiences of a teenage girl struggling to find her way in a world where Uyghurs trying to live a traditional lifestyle are prohibited from doing so because of the Chinese government's repressive cultural and ethnic policies. Many observers feel that Uyghur identity, culture, language, and religion are in danger of being lost forever. This book could almost be read as a handbook for young Uyghurs dealing with the pressures of modern society in East Turkestan.

The author's care and hard work have given us a story that has never been told before. I am personally indebted to her for telling it so well.

The Uyghur people live in a region of the People's Republic of China called Xinjiang. The Uyghurs call it East Turkestan. I have traveled there, to the ancient city of Hotan, which lies along the path of the old Silk Road at the southern edge of the vast Taklamakan Desert. The wind from that desert blew sand and dirt into my face and pummeled the building where I stayed until, at last, a miraculous rain fell to clear the air and refresh the land. I visited the surrounding countryside and watched corn being ground between two huge stones at the grist mill and walked beside the millstream. I purchased a hard-boiled egg at the local market. What I remember most is a young Uyghur girl who offered me a peach from her family's orchard as I stood with my guide watching her grandfather weave a willow basket in the front yard of their home.

Sometime later I learned that Uyghur girls were being forced to work in Chinese factories far from their homes and families, that local cadres had quotas to fill and that the girls were given no choice. This was a story I wanted to tell. The young peasant girl who had offered me a peach became Mehrigul, and I imagined what her life might be.

The Uyghur people are distinct from the Chinese. Their physical appearance, their language and customs, and their Muslim religion are more like those of the Turkic peoples of Central Asia, in countries such as Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, than those of the Chinese. The Uyghurs established their own country and their own identity two thousand five hundred years ago. Though their Islamic identity can be traced to A.D. 934, when the city of Kashgar became one of the major learning centers of Islam, over the centuries they have been dominated by many different rulersâamong them the Mongol leader Genghis Khan and the imperial powers of China's Qing Dynasty. Their sparsely populated land of great deserts and high mountain ranges is hard to defend. People live in separate oasis towns, more loyal to their own oases than to any national state. Even so, the Uyghurs preserved their own language and culture. They lived as they had from the earliest time of the old Silk Road, managing their limited resources of land and water and continuing their rich tradition as expert craftsmen and traders.

Then, in 1949, the People's Republic of China discovered that the Uyghur homeland had an abundance of coal, oil, and gas reserves, in addition to gold and precious metals. The Han Chinese, with full support from the Communist regime, rapidly took over. By 2000, census figures showed that the number of Uyghurs in East Turkestan had shrunk from 90 percent of the population to less than half.

The Uyghurs protested the invasion of their homeland. The authorities responded with punishments. Though the Uyghurs practice a moderate form of Islam and are themselves wary of Muslim extremists, the authorities made an even greater effort to suppress them after the attack on the World Trade Center in 2001, with the excuse that all Uyghurs were potential terrorists. Uyghurs who take part in peaceful protests to protect their land and their distinct identity are sent to reeducation camps or prisons; many are tortured or executed. Such things as teaching religion to a minor and having a copy of the book

Dragon Fighter,

written by Rebiya Kadeer, the exiled leader of the Uyghur people, are considered criminal.

Unlike most of East Turkestan, the Hotan area where Mehrigul lives was left alone by the Chinese; it lies between the Taklamakan, one of the world's largest deserts to the north, and the Kunlun, one of the highest mountain ranges to the south. The area long remained a major stronghold of a pure Uyghur culture. In 2000 the population was 96.4 percent Uyghur. That has changed. The government is modernizing the city of Hotan; there is a new covered mall and supermarkets to attract tourists, although the ancient Sunday bazaar is of greater interest. There are discos and nightclubs. As the Han Chinese population in the area grows, land is being taken from the Uyghurs and their careful conservation of the water supply is being ignored. Uyghur teachers who do not speak Mandarin are being replaced; jobs created by the government are offered to the Han Chinese.

Memories of ancestors who have been one with their own land for centuries linger in the minds of the Uyghurs. The Uyghurs understand their bargain with the desert, the windblown sands from the Taklamakan that from time to time sting people's faces and bury their fragile oasis in a layer of sand. There is no escape from this timeless force of nature. The people cover their faces, shut their doors, yet the sand seeps through the weave of the cloth, the cracks in the walls. It passes. They return to their fields, their trades. As long as the spirit of their ancient culture remains true, they can endure.

But a storm has come to which there is no end. There has been no bargain made, no good understanding. The winds of change sweep over the Uyghurs in the name of progress. They struggle to make their voices heard.

A visitor traveling to Hotan and the countryside today would still see donkey carts, women wearing headscarves, men in their traditional four-cornered

dopa

caps, but Mehrigul's farm at the end of the poplar-lined lane might now belong to a family of Han Chinese.

This book about the Uyghur people was made possible by the late Tom Wilson. Tom believed that travel to other countries was about meeting people and gaining an understanding of how they lived, rather than being an onlooker at established sites. Tom's World Craft Tours centered on visiting craftsmen and their families and watching them at work. Over the years he became a welcomed guest in many homes and shared this with a few who were privileged to travel with him, including me. Thank you, Tom, and thanks to Abdul, our Uyghur guide, who gave voice to the people we met in the countryside near the city of Hotan.

I wrote my novel with the help and support of my writers' groupâLaurie Calkhoven, Bethany Hegedus, and Kekla Magoonâwho were with me every Thursday from the first rough draft through to the final revision. Just showing up was important; you gave so much more. I was lucky to have Ellen Howard, Liza Ketchum, the late Norma Fox Mazer, and Tim Wynne-Jones expect, and demand, the best of me while I earned my MFA degree from Vermont College of Fine Arts.

My deepest thanks to my agent, Marietta Zacker, who believed in me and my writing and found the perfect home for my novel. I am forever grateful to my editor, Dinah Stevenson, who cared about my story and helped to make every word in it the right one.

When I questioned my right to author a novel about a Uyghur girl living in Hotan, I sought the counsel of the Uyghur American Association in Washington, D.C. Henryk Szadziewski, manager of the Uyghur Human Rights Project, and Amy Reger, senior researcher, offered encouragement and guidance. They also introduced me to Mamatjan Juma, editor and international broadcaster at Radio Free Asia in Washington, D.C. He undertook the job of reading the manuscript and pointing out where the facts in my story veered too far from the truth. I am eternally grateful to him for keeping the story true to the spirit of the Uyghur people. Any errors or fictional liberties that remain, of course, are mine.

I wish to acknowledge Dr. Rachel Harris, ethnoÂmusicologist at the University of London, for giving permission to use her English translations of the Uyghur songs.

And nothing would have been accomplished without the love and support of Bill.

J

OSANNE

L

A

V

ALLEY

traveled across the Taklamakan Desert to the Hotan region of China, where she spent time among the Uyghur. The recipient of an MFA in writing children's books from Vermont College, Ms. LaValley lives in New York City.

The Vine Basket

is her first novel.