The Wald

Authors: Jason Born

THE WALD

By

Jason Born

WORKS WRITTEN BY JASON BORN:

THE WALD CHRONICLES: THE WALD

THE NORSEMAN CHRONICLES: THE NORSEMAN

THE NORSEMAN CHRONICLES: PATHS OF THE NORSEMAN

THE NORSEMAN CHRONICLES: NORSEMAN CHIEF

COPYRIGHT

THE WALD. Copyright © 2013 by Jason Born. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission.

DEDICATION

Pete & Deb

Your encouraging words are blessings to me.

Your daughter

ain’t bad either.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

It turns out that telling the story is the fun and easy part. Getting the book from a rough Word document into something that readers may find compelling enough in order to part with a small bit of their hard-won money, is daunting. Thankfully, there are several folks who offered their assistance in the process.

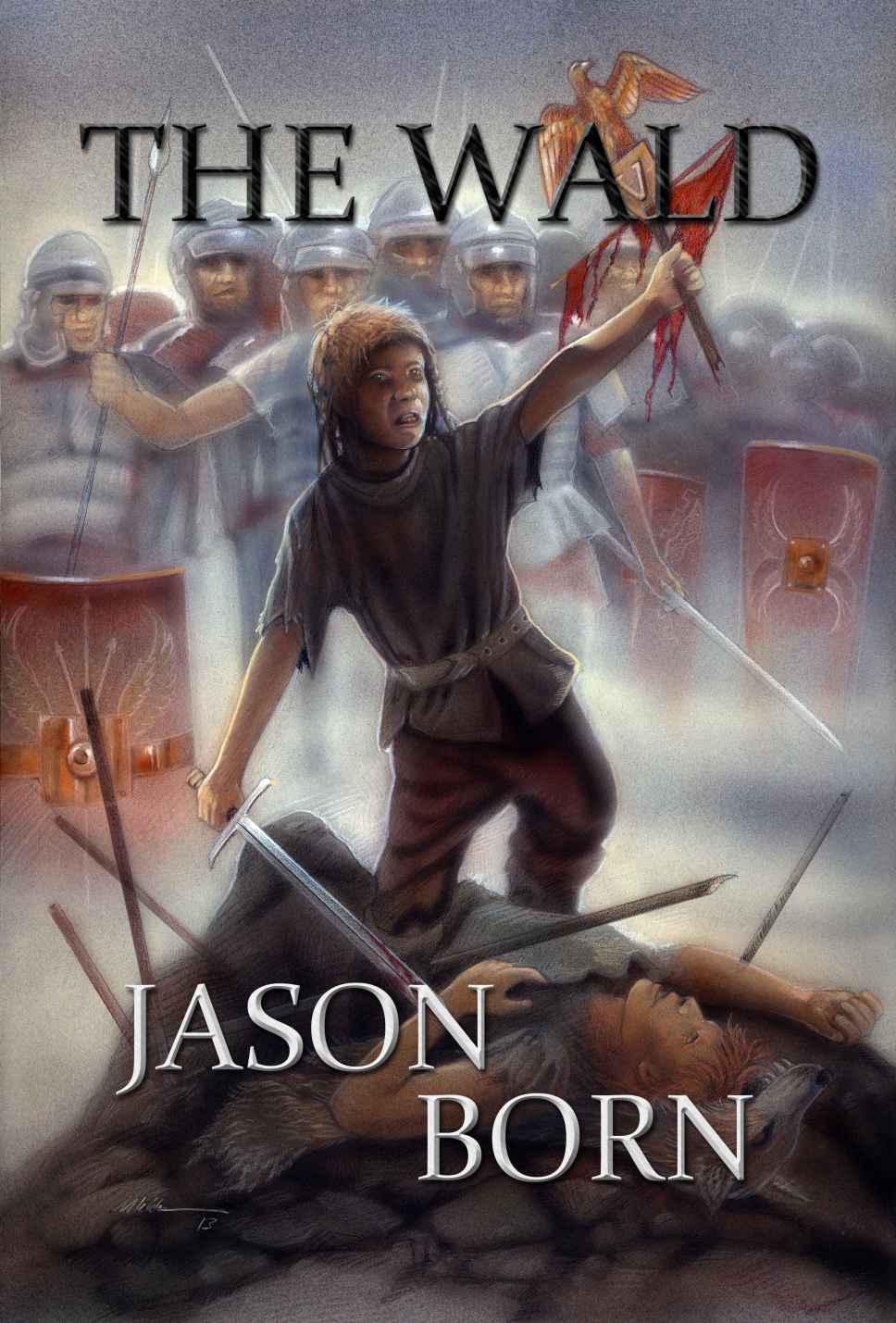

Michael Calandra captured the spirit of this first work in The Wald Chronicles with his pencils and brush. It seems Michael gets busier each time I show up at his door to request another cover, yet he continues to find time to fit me in and complete his task in stellar fashion.

I’m beginning to think that Mike Brogan will have a new career someday. That is, if we even have cartographers anymore. With his magical electronic pen, he etches out the lands and waters of my stories. For my money, it is always best to read historical fiction with at least one map in order to understand the characters and their relationships to one another.

Mike gives us four in The Wald! Thank you, Mike.

Along the way, I began to refer to my editor, Kate

Frishman, as Wise and Fair. The former certainly captures her abilities and experience. Kate mapped out my scenes and helped me chop where necessary. As we moved through the editing process, I started to question my use of the latter description. She was, of course, fair. However, her brutal honesty left me with more than a few emotional scars and a hint of internal bleeding. I am indebted to her for all her help. I am a better writer as a result of Kate’s guidance.

NOTES FOR

THE CURIOUS READER

Concerning Roman Legions:

8 men in a contubernium

10 contubernia in a century (80 men)

6 centuries in a cohort (480 men)

10 cohorts in a legion (4,800 men plus auxiliary infantry and cavalry)

Concerning Place Names:

Albis River is the Elbe

Amisia River is the Ems

Danuvius River is the Danube

Gaul is more or less modern France

Lugdunum is modern Lyons

Lupia River is the Lippe

Mare Caspium is the Caspian Sea

Mare Germanicum is the North Sea

Mogontiacum is modern Mainz

Oppidum Ubiorum is modern Cologne

Rhenus River is the Rhine

Vetera is modern Xanten

Visurgis River is the Weser

MAP OF THE WORLD ACCORDING TO AGRIPPA

MAP OF NORTHERN ROMAN EMPIRE

MAP OF THE TRIBES

MAP OF BATTLE AT THE NARROW PASS

PROLOGUE

16 B.C.

The Celtic Gaul were fat and the Sugambrians, driven out from their black forests by hunger, were thin. West of the Rhenus, the Gaul, with their rich farmland, had produced a bountiful crop for themselves, and, more importantly, for their powerful overlords, the Romans. These subdued Gaul, with their subdued Gallic towns each had a storehouse that, at harvest’s end, would be stuffed from corner to corner with millet, wheat, or barley, awaiting the Roman tax collectors to come and take away their share to feed the hungry legions that occupied the region.

Berengar was bent on getting to the stores first. He was seven years old that autumn and had convinced himself he was already a man. His

old father, Adalbern, which meant noble bear, had done nothing but confirm Berengar’s budding supposition when he told the boy to come along on the raid for plunder and food. Even now, as the two Sugambrians, father and son, rode horses at the fore of a raiding force of two thousand men, Berengar felt as if it was he alone who commanded these warriors. His army had been assembled from all the tribes’ villages within a three day ride and eagerly marched into the heart of Gaul on spindly legs.

Already a

t his young age, Berengar hated the Gaul. According to stories told over the hearth it had been the same for his father and his father’s father before him. Despising the Gaul was a well-honed pastime among all men who lived east of the Rhenus River. Over his short life he believed he had come to loathe them more with each passing year. But his ever increasing hostility did not stem from anything new the Gaul had done. No. It came from the new manner in which the Gaul chose to speak of his people and all the tribes east of the Rhenus. The Gaul had begun using the same words that the Romans used to describe his people. They called the eastern tribes wild men, or unruly beasts, or untamed, or savage. They acted as if it was not just a generation or two ago that they enjoyed the freedom of calling their various cities home to their own set of tribes.

Adalbern laughed at these derogatory terms and he laughed harder at Berengar’s mountainous contempt coming from such a miniscule, rail-thin body.

“What upsets you so?” Adalbern asked as their force approached the great River Rhenus to cross into enemy territory.

“It’s the way these Romans goad the Gaul into demeaning us.”

Adalbern erupted in uproarious laughter. “Demeaning us?” he stuttered out while spittle sprang from his mouth, falling onto his horse’s mane and into his own long beard. Adalbern was prone to gaining weight easily, but, with poor harvests for two years straight, his large frame was now gaunt, with skin stretched taut over jutting bones. Normally this laughing fit would have led to his ample belly dancing above his trousers. Now, however, the lean man could just barely wiggle his outsized jerkin with his wriggling.

“Who’s demeaned?” Adalbern called to Gundahar, a soldier born

of minor noble birth whose cleft palate made his survival this far into adulthood miraculous. “Out with it, you ugly cur, who is demeaned, us or the Gaul?”

Gundahar marched directly behind father and son, his feet still dry as the autumn rains had yet to begin. The man snorted and snuffled in his terrible lisp, “The Gaul demean themselves by living under the rule of women.” Berengar looked straight ahead to the river waters idling by. He could

never look directly at Gundahar; he found the sight too repulsive. Yet despite his grotesque features, Berengar knew the man was his father’s closest confidant and advisor.

“And why are the Romans women?” asked Adalbern.

“Don’t you know?” asked Gundahar, now having fun. “Have you not seen them? Surely, Master Berengar, you’ve seen them by now?”

He hadn’t

, as far as the elders knew. That was not entirely true, though. Berengar and two friends snuck away from the dark forests earlier that summer to peer across the great river at the new town called Oppidum Ubiorum, named by the Romans to honor the traitorous tribe of Ubians that had allied with those interlopers. While the boys had lain on their bellies in the dirt on the wooded hillside, two Roman cavalrymen came to the opposite shore and let their horses drink. Berengar had seen a soldier wearing chain mail over the shoulders and belted at the waist before, but those men on their mounts that day wore something altogether different. The soldiers looked so frightening in their glittering segmented plate cuirasses, that the three boys imagined them capable of bounding the river with one jump and roasting each of them over a fire at the end of their lances. All three lads raced back home; too ashamed to say anything about their fear to their fathers.

Gundahar went on, “They’re women because they dress and look as such. They are incapable of growing beards as all proper men should. Their faces are as smooth as the finest Cheruscan princess. The Romans even w

ear dresses more fitting of women.” Then he added, “Even though they’re women, I’ll happily kill them and their Gallic chattel to again have a belly full of food.”

“You see there, son? The Gaul lash out with words because of their impotence. Smooth-faced babies rule them.” The men in the nearest ranks laughed.

Berengar looked back at them, hair over their ears, bearded, dirty, thin. His confidence from moments ago vanished. Would any of them even survive if this hungry rabble came across one of the feared Roman legions or their newly-trained Gallic auxiliary forces?

The small army came to the edge of the wood

s where a clear line marked the dying autumn grasses of a clearing covered in white frost from the, as of yet, green bramble under the tree canopy untouched by the icy blanket. Adalbern ordered the men to begin making rafts from the trees around them so they could cross the deep, wide River Rhenus. Berengar scooted a leg over his mount to jump down and stretch, but his father held the boy. “Ride with me.”

Dutifully, Berengar settled back onto his horse, a tame beast, many years older than the boy. He clicked his tongue and soon he was next to his father riding along the river, the sound of iron axes echoing in the distance. Adalbern said nothing for a long time so his son looked across the expanse of water to Gaul. There were hills and thick trees running along the western shore just as there were there on the eastern side. The difference, Berengar had heard, was that further from the river to the west, Gaul opened into rolling land, capable of growing abundant crops for thousands upon thousands of people

. So much food was grown that the Gaul could still get fat after paying off their masters in Rome.

To the east, toward the land of his people, the Sugambrians, the forest

, or wald, seemed to grow thicker, darker. It was a land more beautiful than Berengar could conjure even in his imagination. It was certainly the type of land the gods inhabited, which was why stories abounded about holy and unholy beings living in the forest’s dark glens. There was trouble with his fatherland, though. The gods could reside in its glory without worrying about their bellies consuming themselves. The same was not true of his village, where his father served as an elder, elected to warlord in times of strife – times such as now.

“Will we ever take her?” Berengar asked Adalbern, referring to

the land of the Gaul.

“By Teiwaz, no!

We can’t hope to make war with those people and their allies. If we meet a legion, we strike then flee.”

“Then what are we doing now, if not war?”

“Son, we are feeding our women so that they can produce milk for our young. We need no more land than our own.”

“But won’t the act bring war upon us, father?”

“You ask too many questions.” They rode on in the chilly morning air in full view of the opposite bank. Their army was in a remote region of the Rhenus and Adalbern had little fear of arousing suspicion or any alarm. In fact, long before the Romans came with Julius, the Rhenus was a conduit to spread news, goods, and people. No more. Now it was the boundary between two worlds.

Then the old Sugambrian nobleman pulled his horse to a slow stop. “I suppose we could bring w

ar. If our actions in these coming days do bring the Gaul or, worse yet, the Romans’ wrath, all the peoples – Sugambrians, Cheruscans, Suebians – would be better off if the Muspelheim came to us.”

The boy looked worried as his father mentioned the fiery end to the world which

had been foretold since the beginning when the gods created man. Berengar’s eyes filled with water as he sat there on the folded blanket he used as a saddle. “You may cry all you wish here and now, but you’ll never shed tears in front of our people. Our family is populated by men who lead. We don’t weep like children. I brought you out here to tell you how to stay alive when we raid the Gallic towns. Are you listening?”

“Yes

, father,” answered the boy, wishing he was among the women and children tossing discs of frozen cow dung with his neighbors.

“I will lead

these raids from the front of our columns. A nobleman of the Sugambrians must inspire and so should his son if he is to lead men one day. But that does not mean I’ll throw my boy onto the hapless spear of a lucky Gaul as a sacrifice. You’ll dismount before the raids and follow close behind Gundahar. He’ll tell you what to do. You won’t stray to the right or left. You’ll stay on the harelip’s ass.” Berengar, nodding, stared wide-eyed at the most powerful man in the world, his father. Adalbern asked, “Now what will you do when we raid?”

“I’ll stay behind Gundahar.”

“Yes. Will you ask him asinine questions?”

Berengar shook his head.

“Correct. Come back to the men once you’ve dried your eyes.”

Adalbern twitched his horse’s reins and the beast reacted instantly with a skip to the left, back the way they had ambled only moments ago. His boy, ragged and hungry, sat alone on his motionless old horse

worrying that he would disappoint his people and his father when the attacks began. Berengar gave a great sniff while trying to wipe the drainage from his nose that now sat on his lip. Soon he jumped to the ground and stuck a hand in the river, letting the old nag stand idly by. Berengar splashed his face with the cold water to wipe away the remnants of redness and snot. Then, after leading his horse to a fallen log that he could use as a step ladder, the boy climbed on and trotted off to join his father’s army, his confidence slowly returning, his chin held high.

. . .

After three more days and what seemed to Berengar a very circuitous route, his army – the boy was back to thinking of it as his army – ascended a hillside to hide itself among a copse of trees. Moments earlier, his father’s runners had come back on their lean legs saying there was a prosperous village ahead unaware of their presence. The wheat and barley harvest had been brought in, they reported. All was quiet.

Only once since they entered Caesar Augustus’ Gaul had they seen anyone and that had only been an old couple living in an isolated hovel in the crook of a tiny stream. The man had been relieving himself when Berengar and his father had crested a hill and come into the old peasant’s line of sight. After taking in the image of scores of filthy Sugambrians marching toward him, the man shouted inside to his wife while cinching his trousers. Soon, both were running fast

with their aged feeble gaits to the perceived protection of a nearby wood. Adalbern had let them go, not wanting to waste time on prey with such limited chance for spoils.

Today

was to be different. Down in the prosperous village would be Berengar’s first encounter of any real proximity with the Gaul.

“Sugambrians,” his father called, just loud enough to be heard by the heads of families who had huddled around him for final instructions. “We will take this town and their goods. We will plunder them. Kill who you must. I hope most of them flee. If they do run, do not pursue. We are here for booty, not to conquer. Once we’ve taken the village, I want everything brought out and taken. We cannot waste precious time meeting or planning once we’ve begun this thing. When we are laden with goods, we move to the next village and the next and the next, until we are so heavy burdened or enough time has passed that we must flee a

head of a counterattack that may come from the Roman governor’s legions.”

The men nodded. They would not spend any time planning maneu

vers, intricate or simple. The way of war among the peoples east of the Rhenus was blunt and savage. It was massing, shouting, and killing. It was drawing enough blood so the other side fled.

So it was that Berengar scrambled down his horse, tying the reins off on the nearest tree.

Gundahar grabbed the boy’s arm roughly and dragged him in place behind him. “Keep up,” was all the ugly man said until he heard the near silent whisper of Berengar drawing his small blade. “Don’t hurt yourself,” the older man added without turning to look.

Berengar’s father

sat mounted on his horse. The animal sensed the pending excitement, snorting, shaking his massive head so that his dirt-matted mane slapped against his neck, stamping his hooves into the fallen leaves, still wet from a morning rain. Other than Adalbern and Gundahar’s back, the boy could see very little. He was in the second rank of what seemed, to him, an unending line of men. Some of the men urinated at their feet while they waited for the order to move, making the most of their last moments of peace. Berengar swallowed hard before realizing he, too, had to relieve himself.