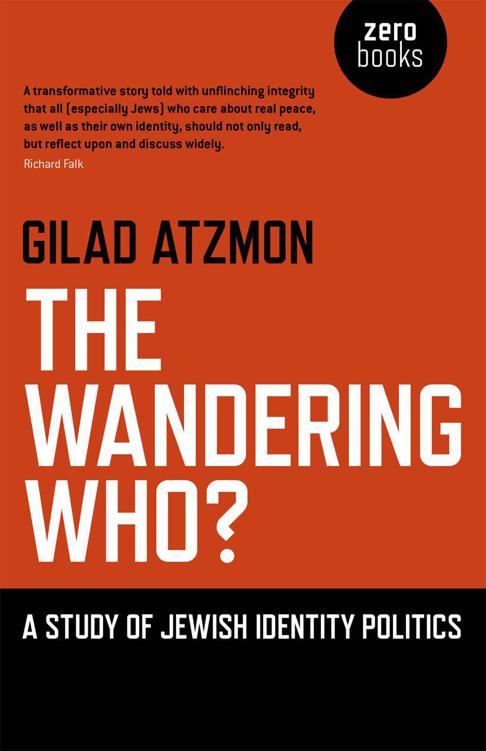

The Wandering Who: A Study of Jewish Identity Politics

Read The Wandering Who: A Study of Jewish Identity Politics Online

Authors: Gilad Atzmon

WHAT PEOPLE ARE SAYING ABOUT

THE WANDERING WHO?

‘Gilad Atzmon has written an absorbing and moving account of his journey from hard core Israeli nationalist to a de-Zionized patriot of humanity and passionate advocate of justice for the Palestinian people. It is a transformative story told with unflinching integrity that all (especially Jews) who care about real peace, as well as their own identity, should not only read, but reflect upon and discuss widely.’

Professor Richard Falk

,

Albert G. Milbank Professor of International Law Emeritus, Princeton University, author of over 20 books, and UN Special Rapporteur for Occupied Palestinian Territories.

‘Gilad Atzmon has written a fascinating and provocative book on Jewish identity in the modern world. He shows how assimilation and liberalism are making it increasingly difficult for Jews in the Diaspora to maintain a powerful sense of their 'Jewishness.' Panicked Jewish leaders, he argues, have turned to Zionism (blind loyalty to Israel) and scaremongering (the threat of another Holocaust) to keep the tribe united and distinct from the surrounding goyim. As Atzmon’s own case demonstrates, this strategy is not working and is causing many Jews great anguish. The Wandering Who? should be widely read by Jews and non-Jews alike.’

John J. Mearsheimer

is the R. Wendell Harrison Distinguished Service Professor of Political Science at the University of Chicago

‘Gilad Atzmon‘s The Wandering Who? is a series of brilliant illuminations and critical reflections on Jewish ethnocentrism and the hypocrisy of those who speak in the name of universal values and act tribal. Relying on autobiographical and existential experiences, as well as intimate observations of everyday life, both

informed by profound psychological insights, Atzmon does what many critics of Israel fail to do; he uncovers the links between Jewish identity politics in the Diaspora with their ardent support for the oppressive policies of the Israeli state.

Atzmon provides deep insights into “neo-ghetto” politics. He has the courage - so profoundly lacking among western intellectuals - to speak truth to the power of highly placed and affluent Zionists who shape the agendas of war and peace in the English-speaking world. With wit and imagination, Atzmon’s passionate confrontation with neo-conservative power grabbers and liberal yea sayers sets this book apart for its original understanding of the dangers of closed minds with hands on the levers of power.

This book is more than a “study of Jewish identity politics” insofar as we are dealing with a matrix of power that affects all who cherish self-determination and personal freedom in the face of imperial and colonial dictates.’

Professor James Petras

,

Bartle Professor of Sociology at Binghamton University, New York, author of more than 62 books including The Power of Israel in the United States.

‘Gilad Atzmon’s book, The Wandering Who? is as witty and thought provoking as its title. But it is also an important book, presenting conclusions about Jews, Jewishness and Judaism which some will find shocking but which are essential to an understanding of Jewish identity politics and the role they play on the world stage.’

Karl Sabbagh

is a journalist, television producer and the author of several books including A Rum Affair, Power Into Art, Dr Riemann’s Zeros and Palestine: A Personal History. He is currently the publisher of Hesperus Press

‘Atzmon’s insight into the organism created by the Zionist movement is explosive. The Wandering Who? tears the veil off of Israel’s apparent civility, its apparent friendship with the United States, and its expressed solicitude for Western powers, exposing beneath the assassin ready to slay any and all that interfere with its tribal focused ends.’

Professor William A. Cook

,

Professor of English at the University of La Verne in southern California, and author of The Rape Of Palestine.

‘The Wandering Who? features Gilad Atzmon at his delightful and insightful best: engaging, provocative and persuasive.’

Jeff Gates

,

author of Guilt By Association: How Deception and Self-Deceit Took America to War

‘The Wandering Who? is a pioneering work that deserves to be read and Gilad Atzmon is brave to write this book!’

Dr. Samir Abed-Rabbo

,

author and Professor Emeritus in the field of international law. He is director of the Center for Arabic and Islamic Studies in Brattleboro, Vermont and the former Dean of The Jerusalem School for Law and Diplomacy.

The Wandering Who?

A Study of Jewish Identity Politics

The Wandering Who?

A Study of Jewish Identity Politics

Gilad Atzmon

Winchester, UK

Washington, USA

First published by Zero Books, 2011

Zero Books is an imprint of John Hunt Publishing Ltd., Laurel House, Station Approach,Alresford, Hants, SO24 9JH, UK

[email protected]

www.o-books.com

For distributor details and how to order please visit the ‘Ordering’ section on our website.

Text copyright: Gilad Atzmon 2011

ISBN: 978 1 84694 875 6

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publishers.

The rights of Gilad Atzmon as author have been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Design: Lee Nash

Printed in the UK by CPI Antony Rowe

Printed in the USA by Offset Paperback Mfrs, Inc

We operate a distinctive and ethical publishing philosophy in all areas of our business, from our global network of authors to production and worldwide distribution.

‘The Nazis made me afraid to be a Jew, and the Israelis make me ashamed to be a Jew.’

Israel Shahak

Foreword

My grandfather was a charismatic, poetic, veteran Zionist terrorist. A former prominent commander in the right-wing Irgun terror organisation, he had, I must admit, a tremendous influence on me in my early days. He displayed unrelenting hatred toward anything not Jewish. He hated Germans; consequently, he would not allow my dad to buy a German car. He also despised the British for colonising his ‘promised land’. I can only assume that he didn’t detest the Brits as much as the Germans, however, as he did allow my father to drive an old Vauxhall Viva.

He was also pretty cross with the Palestinians for dwelling on the land he was sure belonged to him and his people. Often, he would wonder: ‘These Arabs have so many countries, why do they have to live on the exact same land that was ‘given’ to us by our God?’ More than anything, though, my grandfather hated Jewish leftists. Here it is important to mention that as Jewish leftists have never produced any recognised model of automobile, this specific loathing didn’t mature into a conflict of interests between him and my dad.

As a follower of right wing revisionist Zionist Zeev Jabotinsky,

1

my Grandfather obviously realised that Leftist philosophy together with any form of Jewish value system is a contradiction in terms. Being a veteran right-wing terrorist as well a proud Jewish hawk, he knew very well that tribalism can never live in peace with humanism and universalism. Following his mentor Jabotinsky, he believed in the ‘Iron Wall’ philosophy. Like Jabotinsky, my grandfather respected Arab people, he had high opinions of their culture and religion, yet he believed that Arabs in general, and Palestinians in particular, should be confronted fearlessly and fiercely.

Quoting the anthem of Jabotinsky’s political movement my grandpa would often repeat:

From the pit of decay and dust

Through blood and sweat

A race will arise to us,

Proud, generous and fierce.

My Grandfather believed in the revival of the pride of the ‘Jewish race’, and so did I in my very early days. Like my peers, I didn’t see the Palestinians around me. They were undoubtedly there – they fixed my father’s car for half the price, they built our houses, they cleaned the mess we left behind, they

schlepped

boxes in the local food store, but they always disappeared just before sunset and appeared again before dawn. We never socialised with them. We didn’t really understand who they were and what they stood for. Supremacy was brewed into our souls, we gazed at the world through racist, chauvinistic binoculars. And we felt no shame about it either.

At seventeen, I was getting ready for my compulsory IDF service. Being a well-built teenager fuelled with militant enthusiasm, I was due to join an air force special rescue unit. But then the unexpected happened. On a very late night jazz programme, I heard Bird (Charlie Parker) with Strings.

I was knocked down. The music was more organic, poetic, sentimental and

wilder

than anything I had ever heard before. My father used to listen to Bennie Goodman and Artie Shaw, and those two were entertaining – they could certainly play the clarinet – but Bird was a different story altogether. Here was an intense, libidinal extravaganza of wit and energy. The following morning I skipped school and rushed to Piccadilly Records, Jerusalem’s number one music shop. I found the jazz section and bought every bebop recording they had on the shelves, which probably amounted to two albums. On the bus home, I realised that Parker was actually a black man. It didn’t take me by complete surprise, but it was kind of a revelation. In my world, it was only Jews who were associated with anything good. Bird was the beginning of a journey.

At the time, my peers and I were convinced that Jews were indeed the Chosen People. My generation was raised on the magical victory of the Six-Day War. We were totally sure of ourselves. As we were secular, we associated every success with our omnipotent qualities. We didn’t believe in divine intervention, we believed in ourselves. We believed that our might originated in our resurrected Hebraic souls and flesh. The Palestinians, for their part, served us obediently, and it didn’t seem at the time that this situation was ever going to change. They displayed no real signs of collective resistance. The sporadic so-called ‘terror’ attacks made us feel righteous, and filled us with eagerness for revenge. But somehow, amidst this orgy of omnipotence, and to my great surprise, I came to realise that the people who excited me most were actually a bunch of black Americans – people who had nothing to do with the Zionist miracle or with my own chauvinist, exclusivist tribe.

Two days later I acquired my first saxophone. It’s a very easy instrument to get started on – ask Bill Clinton – but learning to play like Bird or Cannonball Adderley seemed an impossible mission. I began to practise day and night, and the more I did, the more I was overwhelmed by the tremendous achievement of that great family of black American musicians I was beginning to know closely. Within a month I learned about Sonny Rollins, Joe Henderson, Hank Mobley, Thelonious Monk, Oscar Peterson and Duke Ellington, and the more I listened the more I realised that my Judeo-centric upbringing was, somehow, totally misleading.

After one month with a saxophone shoved in my mouth, my military combatant’s enthusiasm disappeared completely. Instead of flying choppers behind enemy lines, I started to fantasise about living in New York, London or Paris. All I wanted was a chance to listen to the jazz greats play live, for it was the late 1970s and many of them were still around.

Nowadays, youngsters who want to play jazz tend to enrol in a music college. It was very different when I was coming up. Those who wanted to play classical music would join a conservatory, but those who wanted to play for the sake of the music itself would stay at home and swing around the clock. There was no jazz education in Israel at that time, and my hometown, Jerusalem, had just a single, tiny jazz club, housed in an old, converted picturesque Turkish bath. Every Friday afternoon it ran a jam session, and for my first two years in jazz, these jams were the essence of my life. I stopped everything else. I just practised day and night, even while sleeping, and prepared myself for the next ‘Friday Jam’. I listened to the music and transcribed some great solos. I practiced in my sleep imagining the chord changes and flying over them. I decided to dedicate my life to jazz, accepting the fact that, as a white Israeli, my chances of making it to the top were rather slim.

I did not yet realise that my emerging devotion to jazz had overwhelmed my Jewish nationalist tendencies; that it was probably then and there that I left Chosen-ness behind to become an ordinary human being. Years later, I would indeed come to see that jazz had been my escape route.

Within months, though, I began to feel less and less connected to my surrounding reality. I saw myself as part of a far broader and greater family, a family of music lovers, admirable people concerned with beauty and spirit rather than land, mammon and occupation.

However, I still had to join the IDF. Though later generations of young Israeli jazz musicians simply escaped the army and fled to the Mecca of jazz, New York, such an option wasn’t available for me, a young lad of Zionist origins in Jerusalem. The possibility didn’t even occur to me.

In July 1981 I joined the Israeli army, but from my first day of service I did my very best to avoid the call of duty – not because I was a pacifist, nor did I care that much about the Palestinians. I just preferred to be alone with my saxophone.

In June 1982, when the first Israel–Lebanon war broke, I had been a soldier for a year. It didn’t take a genius to figure out the truth. I knew our leaders were lying, in fact, every Israeli soldier understood that this was a war of Israeli aggression. Personally, I no longer felt any attachment to the Zionist cause, Israel or the Jewish people. Dying on the Jewish altar didn’t appeal to me anymore. Yet, it still wasn’t politics or ethics that moved me, but rather my craving to be alone with my new

Selmer Paris Mark IV

saxophone. Playing scales at the speed of light seemed to me far more important than killing Arabs in the name of Jewish suffering. Thus, instead of becoming a qualified killer I spent every possible effort trying to join one of the military bands. It took a few months, but I eventually landed safely in the Israeli Air Force Orchestra (IAFO).

The IAFO was uniquely constituted. You could be accepted for being an excellent musician or promising talent, or for being a son of a dead pilot. The fact that I was accepted knowing that my dad was still amongst the living reassured me: for the first time, I considered the possibility that I might possess musical talent.

To my great surprise, none of the orchestra members took the army seriously. We were all concerned with just one thing: our personal musical development. We hated the army, and it didn’t take long before I began to hate the very state that required an Air Force that required a band for it, that stopped me from practising 24/7. When we were called to play for a military event, we would try and play as poorly as we could just to make sure we would never get invited again. Sometimes we even gathered in the afternoon just to

practise

playing badly. We realised that the worse we performed as a collective, the more personal freedom we would gain. In the military orchestra I learned for the first time how to be subversive, how to sabotage the system in order to strive for a personal ideal.

In the summer of 1984, just three weeks before I shed my military uniform, we were sent to Lebanon for a concert tour. At the time it was a very dangerous place to be. The Israeli army was dug deep in bunkers and trenches, avoiding any confrontations with the local population. On the second day we set out for Ansar, a notorious Israeli internment camp in South Lebanon. This experience was to change my life completely.

At the end of a dusty dirt track, on a boiling hot day in early July, we arrived at hell on earth. The huge detention centre was enclosed with barbed wire. As we drove to the camp headquarters, we had a view of thousands of inmates in the open air being scorched by the sun.

As difficult as it might be to believe, military bands are always treated as VIPs, and once we landed at the officers’ barracks we were taken on a guided tour of the camp. We walked along the endless barbed wire and guard towers. I couldn’t believe my eyes.

‘Who are these people?’ I asked the officer.

‘Palestinians,’ he said. ‘On the left are PLO [Palestine Liberation Organisation], and on the right are Ahmed Jibril’s boys [Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine – General Command] – they are far more dangerous, so we keep them isolated.’

I studied the detainees. They looked very different to the Palestinians in Jerusalem. The ones I saw in Ansar were angry. They were not defeated, they were freedom fighters and they were numerous. As we continued past the barbed wire I continued gazing at the inmates, and arrived at an unbearable truth: I was walking on the other side, in Israeli military uniform. The place was a concentration camp. The inmates were the ‘Jews’, and I was nothing but a ‘Nazi’. It took me years to admit to myself that even the binary opposition Jew/Nazi was in itself a result of my Judeo-centric indoctrination.

While I contemplated the resonance of my uniform, trying to deal with the great sense of shame growing in me, we came to a large, flat ground at the centre of the camp. The officer guiding us offered more platitudes about the current war to defend our Jewish haven. While he was boring us to death with these irrelevant

Hasbara

(propaganda) lies, I noticed that we were surrounded by two dozen concrete blocks each around 1m

2

in area and 1.3m high, with small metal doors as entrances. I was horrified at the thought that my army was locking guard dogs into these boxes for the night. Putting my Israeli

chutzpah

into action, I confronted the officer about these horrible concrete dog cubes. He was quick to reply: ‘These are our solitary confinement blocks; after two days in one of these, you become a devoted Zionist!’

This was enough for me. I realised that my affair with the Israeli state and with Zionism was over. Yet I still knew very little about Palestine, about the

Nakba

or even about Judaism and Jewish-ness, for that matter. I only saw then that, as far as I was concerned, Israel was bad news, and I didn’t want to have anything further to do with it. Two weeks later I returned my uniform, grabbed my alto sax, took the bus to Ben-Gurion Airport and left for Europe for a few months, to busk in the street. At the age of twenty-one, I was free for the first time. However, December proved too cold for me, and I returned home – but with the clear intention to make it back to Europe. I somehow already yearned to become a

Goy

or at least to be surrounded by

Goyim

.

***

It took another ten years before I could leave Israel for good. During that time, however, I began to learn about the Israel–Palestine conflict, and to accept that I was actually living on someone else’s land. I took in the devastating fact that in 1948 the Palestinians hadn’t abandoned their homes willingly – as we were told in school – but had been brutally ethnically cleansed by my grandfather and his ilk. I began to realise that ethnic cleansing has never stopped in Israel, but has instead just taken on different forms, and to acknowledge the fact that the Israeli legal system was not impartial but racially-orientated (for example, the ‘Law of Return’ welcomes Jews ‘home’ from any country supposedly after 2,000 years, but prevents Palestinians from returning to their villages after two years abroad). All the while, I had also been developing as a musician, becoming a major session player and a musical producer. I wasn’t really involved in any political activity, and though I scrutinised the Israeli leftist discourse I soon realised that it was largely a social club rather than an ideological force motivated by ethical awareness.