The Way of Wanderlust (15 page)

I hadn't been back there in a decade, and I wondered what tricks memory might have played. But soon we came upon the mysterious rectangular stone foundations that had seemed like ancient ruins to a child's mind. Then the rotting boards and wire mesh of a chicken coop appeared, and I told Jenny how the battered door with the fading skull and crossbonesâ“Look, it's still here!”âhad convinced me pirates once lived there. We stepped over streams and toppled trunks, and I talked about how I used to love to watch the yellow-green buds unfolding like secret messages in spring and how I'd thrash through the crackling leaf-carpets of fall. I told her about bounding rabbits and spindly-legged deer, about the beavers we were convinced were there but never saw and about the dreams that took root in that seemingly endless expanse of rock and tree.

When we got back and told Mom about our journey, her eyes glistened. “When you were little, we used to go for walks in those woods,” she said. “You'd call them adventures and you'd say, âCan we go on an adventure now?' Sometimes we'd see foxes or deer and sometimes we'd just listen to the wind in the trees. I loved that.”

We sat in stillness in the deepening dusk.

In a sense, nothing extraordinary happened that Thanksgiving. But in another sense, something deep and abiding was revealed to me. I understood the fuller meaning of home. Home is a physical structure. It is the people who lived and live in that structure. And it is the memories that were born there and that we carry with us, wherever we go. Home is the house and the woods and the touch football games, the Porters and the picnics and the treacherous pool. Home is my wife and kids and my mom and dad and all the celebrations we sharedâand share still.

And I realized that this is what I'm honoring each Thanksgiving when I make my Connecticut pilgrimage: I'm giving thanks for the home that I carry in my head and in my heart, that roots me when I teeter, lifts me when I tire, connects me to all my earthly adventures past and present and to come, the home that embraces meâand the whole world I cherishâin the bare boughs of love.

![]()

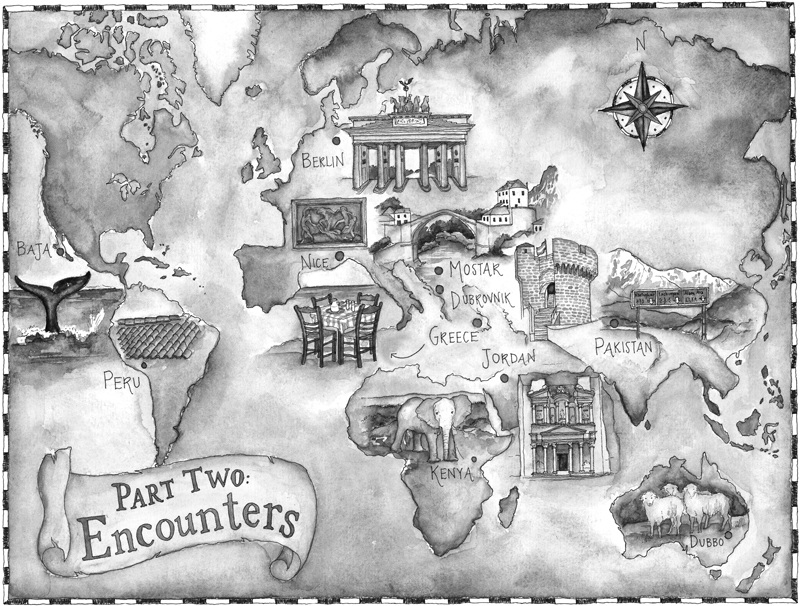

As I mentioned earlier, when I was Travel Editor at the

Examiner

, I tried to make my Sunday column a space where I could talk very personally about people, places, and events from my life. My fervent belief was that if I wrote about these precisely and engagingly enough, they would resonate with readers and trigger connections with similar people, places, events, and lessons in their own lives. “In Love, in Greece, in the Springtime,” about an enigmatic woman who became my confidante and muse when I lived in Athens and who has been a part of my interior life ever since, was one of those columns where I deeply excavated material from my own past, but in a way that I hoped would embrace and not exclude readers. It was also a chance for me to try to articulate the fundamentally life-changing effects that youthful year in Greece had on me. I hoped this piece would kindle readers' memories of similarly life-changing encounters with their muse, wherever and whoever that muse might be.

![]()

IT HAPPENS AT SOME POINT EVERY SPRING:

I will be driving innocently along some rural route, and suddenly a certain slant of sunlight will recall the way the light filtered through the pine trees along the road that wound up the coast from Athens to the little taverna no one seemed to know aboutâno one except Gisela, the beautiful and mysterious woman with whom I had fallen ineluctably in love that spring of 1976.

We would install ourselves in peeling white wooden chairs around a stolid wooden table on the beach, under the pines, and the kindly taverna owner would bring us huge chunks of hard, delicious bread, a salad of feta cheese, tomatoes, cucumbers, and black olives, and glasses of retsina.

We would eat and sip, but mostly we would watch the shimmering sea and listen to the sighing pines, censing the air with their tangy perfume.

I re-create this scene, and suddenly that whole mind-opening, life-transforming Grecian year revives in a sun-flooded succession of images:

I recall the breath-stopping, time-skipping beauty of just-blossomed scarlet poppies against white marble ruins at Olympia.

I recall the Peloponnese mountain family who insisted on sharing their meager Easter feast with my parents and me.

I recall the ethereal geometry and bony patina of the Acropolis at dawn, before the tourists arrived, and the soul-stirring rite of reading Plato, Socrates, and Aristotle as Apollo's first rays illumined the site.

I recall unfathomable connections on the island of Creteâthe magical frescoes and sere splendors of Knossos, and the painter from Chania who showed me the island's harbors and meadows, churches and town squares through his eyes.

I recall the craggy monasteries and worldly monks of sacred Mount Athos, and the sensual abandon of the long, embracing beach at Lindos, on Rhodes, where I communed for a week with a ragtag band of European pilgrims who were all seeking some sort of Aegean answer.

Aegean answers: Hungrily, hesitantly, I would unfold for Gisela my despairs and my dreams, but mostly I would talk about Greece: about the clarity of the rock and the light and how it was teaching me to attend to the present; about the earthy kindness I had encountered everywhere; about the sheer age of the sites and the accumulation of wisdom and sadness and celebration that seemed to hang, poignant, in the Attic air.

Summer came and I leftâfor Africa and then graduate school, a long, winding road. I never wrote to her, never heard from her.

Now, half of my life later, I wonder: Do we craft our memories, or do our memories craft us?

Now, half of my life later, I know: I went to Greece seeking the roots of Western civilization, and returned with a rootlessness I have never lost.

And every spring the owner shuffles toward us, bearing a laden tray. The sea shimmers. The pines cense and sigh.

The Attic sunlight gleams again in Gisela's laughing eyes.

![]()

A year after becoming Travel Editor at the

Examiner

, I went to Australia to attend a travel conference with my wife and two-year-old daughter. This was my first trip to Australia, and while I didn't have time to undertake an ambitious journey throughout the land, I was determined to find some compact way to get outside the cities and experience rural realities. The Outbackâthat vast, mysterious, mostly unpeopled expanseâwas magnetically alluring, its name alone seeming to promise unimaginable adventure. When I researched ways to get there, I discovered the day trip I describe in this story, and the friendly farmer who guided me indelibly into the heart of the country.

![]()

PETER RENDALL SHIELDED HIS EYES

from the midmorning sun and looked out over the green-brown wheat fields and scraggly eucalyptus trees of Dubbo. “Yeah,” he said, “that's about what you get here in Dubbo: sheep, a few cattle, some fields of wheat, oats, and barleyâand lots of wide-open space.”

We had stopped for a “morning tea” of delicious homemade sandwiches, cake, and tea on a dirt road by a dirt field somewhere on the outskirts of Dubbo, a town of 24,000 perched precariously on the edge of Australia's vast and largely uninhabited Outback. After two and a half hours of bumping and bouncing over mostly unpaved roads and along dusty fields, I was taking some time to get used to the stillness.