The White Goddess (50 page)

Authors: Robert Graves

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Mythology, #Literature, #20th Century, #Britain, #Literary Studies, #Amazon.com, #Mysticism, #Retail

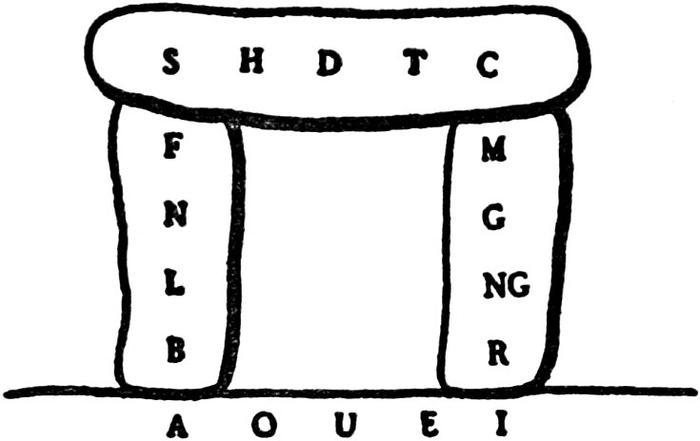

The clue to the arrangement of this alphabet is found in Amergin’s reference to the dolmen; it is an alphabet that best explains itself when built up as a dolmen of consonants with a threshold of vowels. Dolmens are closely connected with the calendar in the legend of the flight of Grainne and Diarmuid from Finn Mac Cool. The flight lasted for a year and a day, and the lovers bedded together beside a fresh dolmen every night. Numerous ‘Beds of Diarmuid and Grainne’ are shown in Cork, Kerry, Limerick, Tipperary and the West, each of them marked by a dolmen. So this alphabet dolmen will also serve as a calendar, with one post for Spring, the other for Autumn, the lintel for Summer, the threshold for New Year’s Day. Thus:

At once one sees the reference to S as a hawk, or griffon, on the cliff; and to M as the hill of poetry or inspiration – a hill rooted in the death letters R and I and surmounted by the C of wisdom. So the text of the first part of Amergin’s song may be expanded as follows:

God

speaks

and

says:I

am

a

stag

of

seven

tines.Over

the

flooded

worldI

am

borne

by

the

wind.I

descend

in

tears

like

dew,

I

lie

glittering,I

fly

aloft

like

a

griffon

to

my

nest

on

the

cliff,I

bloom

among

the

loveliest

flowers,I

am

both

the

oak

and

the

lightning

that

blasts

it.I

embolden

the

spearman,I

teach

the

councillors

their

wisdom,I

inspire

the

poets,I

rove

the

hills

like

a

conquering

boar,I

roar

like

the

winter

sea,I

return

like

the

receding

wave.Who

but

I

can

unfold

the

secrets

of

the

unhewn

dolmen?

For if the poem really consists of two stanzas, each of two triads, ending with a single authoritative statement, then the first ‘Who but I?’ (which does not match the other five) is the conclusion of the second stanza, and is uttered by the New Year God. This Child is represented by the sacred threshold of the dolmen, the central triad of vowels, namely O.U.E. But one must read O.U.E. backwards, the way of the sun, to make sense of it. It is the sacred name of Dionysus, EUO, which in English is usually written ‘EVOE’.

It is clear that ‘God’ is Celestial Hercules again, and that the child-poet Taliesin is a more appropriate person to utter the song than Amergin, the leader of the Milesians, unless Amergin is speaking as a mouth-piece of Hercules.

There is a mystery connected with the line ‘I am a shining tear of the sun’, because Deorgreine, ‘tear of the Sun’, is the name of Niamh of the Golden Hair, the lovely goddess mentioned in the myth of Laegaire mac Crimthainne. Celestial Hercules when he passes into the month F, the month of Bran’s alder, becomes a maiden. This recalls the stories of such sun-heroes as Achilles

1

, Hercules and Dionysus who lived for a time

disguised as girls in the women’s quarters of a palace and plied the distaff. It also explains the ‘I have been a maiden’, in a series corresponding with the Amergin cycle, ascribed to Empedocles the fifth-century

BC

. mystical philosopher. The sense is that the Sun is still under female tutelage for half of this month – Cretan boys not yet old enough to bear arms were called

Scotioi

,

members of the women’s quarters – then, like Achilles, he is given arms and flies off royally like a griffon or hawk to its nest.

But why a dolmen? A dolmen is a burial chamber, a ‘womb of Earth’, consisting of a cap-stone supported on two or more uprights, in which a dead hero is buried in a crouched position like a foetus in the womb, awaiting rebirth. In spiral Castle (passage-burial), the entrance to the inner chamber is always narrow and low in representation of the entrance to the womb. But dolmens are used in Melanesia (according to Prof. W. H. R. Rivers) as sacred doors through which the totem-clan initiate crawls in a ceremony of rebirth; if, as seems likely, they were used for the same purpose in ancient Britain, Gwion is both recounting the phases of his past existence and announcing the phases of his future existence. There is a regular row of dolmens on Slieve Mis. They stand between two baetyls with Ogham markings, traditionally sacred to the Milesian Goddess Scota who is said to be buried there; alternatively, in the account preserved by Borlase in his

Dolmens

of

Ireland,

to ‘Bera a queen who came from Spain’. But Bera and Scota seem to be the same person, since the Milesians came from Spain. Bera is otherwise known as the Hag Of Beara.

The five remaining questions correspond with the five vowels, yet they are not uttered by the Five-fold Goddess of the white ivy-leaf, as one would expect. They must have been substituted for an original text telling of Birth, Initiation, Love, Repose, Death, and can be assigned to a later bardic period. In fact, they correspond closely with the

envoi

to the first section of the tenth-century Irish

Saltair

No

Rann,

which seems to be a Christianized version of a pagan epigram.

For

each

day

five

items

of

knowledgeAre

required

of

every

understanding

person –From

everyone,

without

appearance

of

boasting,Who

is

in

holy

orders.The

day

of

the

solar

month;

the

age

of

the

moon;The

state

of

the

sea-tide,

without

error;The

day

of

the

week;

the

calendar

of

the

feasts

of

the

perfect

saintsIn

just

clarity

with

their

variations.

For ‘perfect saints’ read ‘blessed deities’ and no further alteration is needed. Compare this with Amergin’s:

Who

but

myself

knows

where

the

sun

shall

set?Who

foretells

the

ages

of

the

moon?Who

brings

the

cattle

from

the

house

of Tethra

and

segregates

them?On

whom

do

the

cattle

of Tethra

smile?Who

shapes

weapons

from

hill

to

hill,

wave

to

wave,letter

to

letter,

point

to

point?

The first two questions in the

Song

of Amergin

,

about the day of the solar month and the ages of the moon, coincide with the first two items of knowledge in the

S

alt

air:

‘Who knows when the Sun shall set?’ means both ‘who knows the length of the hours of daylight at any given day of the year?’ – a problem worked out in exhaustive detail by the author of

The

Book

of

Enoch

–

and ‘Who knows on any given day how long the particular solar month in which it occurs will last?’

The third question is ‘Who brings the cattle of Tethra (the heavenly bodies) out of the ocean and puts each in his due place?’ This assumes a knowledge: of the five planets, Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Venus, Saturn, which, with the Sun and Moon, had days of the week allotted to them in Babylonian astronomy, and still keep them in all European languages. Thus it corresponds with ‘the day of the week’.

The fourth question, as the glossarist explains, amounts to ‘Who is lucky in fishing?’ This corresponds with ‘the state of the sea tide’; for a fisherman who does not know what tide to expect will have no fishing luck.

The fifth question, read in the light of its gloss, amounts to: ‘Who orders the calendar from the advancing wave B to the receding wave R; from one calendar month to the next; from one season of the year to the next?’ (The three seasons of Spring, Summer and Autumn are separated by points, or angles, of the dolmen.) So it corresponds with ‘the calendar of the feasts of the perfect saints.’

Another version of the poem found in

The

Book

of

Leacon

and

The

Book

of

the

O’Clerys,

runs as follows when restored to its proper order. The glosses are similar in both books, though the O’Clerys’ are the more verbose.

| | B | I am seven battalions or I am an ox in strength – for strength |

| | L | I am a flood on a plain – for extent |

| | N | I am a wind on the sea – for depth |

| | F | I am a ray of the sun – for purity |

| | S | I am a bird of prey on a cliff – for cunning |

| | H | I am a shrewd navigator – |

| | D | I am gods in the power of transformation – I am a god, a druid, and a man who creates fire from magical smoke for the destruction of all, and makes magic on the tops of hills |

| | T | I am a giant with a sharp sword, hewing down an army – in taking vengeance |

| | C | I am a salmon in a river or pool – for power |

| | G | I am a fierce boar – for powers of chieftain-like valour |

| | NG | I am the roaring of the sea – for terror |

| | R | I am a wave of the sea – for might |