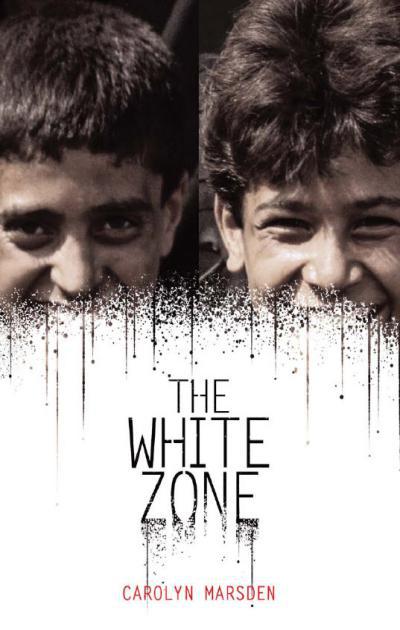

The White Zone

Text copyright © 2012 by Carolyn Marsden

All rights reserved. International copyright secured. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means— electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise— without the prior written permission of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc., except for the inclusion of brief quotations in an acknowledged review.

Carolrhoda Books

A division of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc.

241 First Avenue North

Minneapolis, MN 55401 U.S.A.

Website address:

www.lernerbooks.com

The image in this book is used with the permission of: Front Cover: © John

R. Kreul/Independent Picture Service.

Main body text set in Janson Text LT Std 12/17.

Typeface provided by Linotype AG.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Marsden, Carolyn.

The White Zone / by Carolyn Marsden.

p. cm.

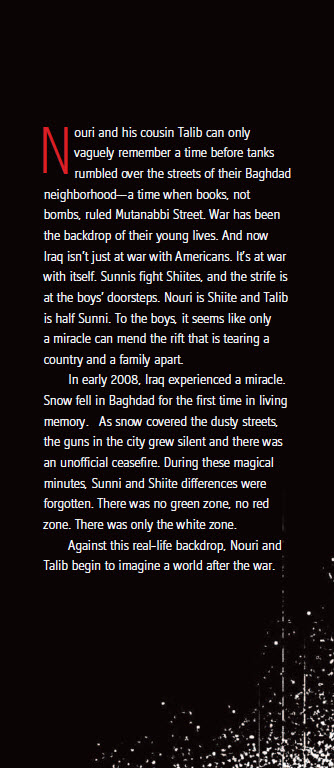

Summary: As American bombs fall on Baghdad during the Iraq War, ten-year-old cousins Nouri and Talib witness the growing violence between Sunni and Shiite Muslims.

ISBN: 978–0–7613–7383–4 (trade hard cover : alk. paper)

1. Iraq War, 2003—Juvenile fiction. [1. Iraq War, 2003—Fiction. 2. Muslims—Fiction. 3. Violence—Fiction. 4. Cousins—Fiction. 5. Baghdad (Iraq)—Fiction. 6. Iraq—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.M35135Wj 2012

2011021227

[Fic]—dc23

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 – SB – 12/31/11

eISBN: 978-0-7613-8724-4

BLACK CAR,

WHITE COFFIN

Nouri covered his eyes against a blast of blowing sand.

When the gust had passed, he opened his eyes to the al-Salam cemetery. Stretching as far as he could see, the flat ground was punctuated by the tombs of the Shiite prophets. The air was cold and Nouri shivered in his new black suit.

In the distance, the glittering gold dome and minarets of the mosque rose into the dusty sky. But Nouri stared only at the white coffin beside the hole in the earth where his uncle would soon be locked away forever. Never again would he smile at Nouri or kick a soccer ball his way.

When the market had been attacked last week by the Sunni martyr, thirty-four people had died. Nouri's uncle had been among the dead.

As the white coffin was lowered into the ground, Mama and A'mmo's other female relatives slapped their faces and wailed in grief.

Nouri's younger cousins, Anwar and Jalal, remained dry-eyed. They were busy bouncing a small rubber ball behind the backs of the grown-ups.

Nouri hoped his cousins wouldn't see the tears wetting his cheeks. Anwar and Jalal hadn't been as close to Mama's youngest brother as he had. They'd never gone with A'mmo to the glassy building in the Green Zone where he worked as a bank teller. They'd never ridden in his black car, which was small, but very shiny.

Nouri had loved that car almost as much as he loved his uncle. Even though the corner store was an easy walk away, A'mmo always drove him there to buy pencils and candies. The kids of the neighborhood had circled the shiny black exterior, running their fingertips over the chrome.

Now everything was different. Baba had driven the family to A'mmo's funeral in that car, traveling the three hours to Najaf City from Baghdad.

Gradually, A'mmo Hakim's relatives made their way to the line of cars that had driven in the convoys from Baghdad and Mosul.

While Mama leaned in to kiss her relatives on both cheeks, Nouri bit his cheeks against the tears building in his throat. A'mmo Hakim was really gone.

Mama climbed into the front seat of the black car and Nouri got in next to the back window. His little sister. Shathaâa large black bow in her hairâscooted to the middle, making room for Mama's sister.

A'mmo Hakim's once-shiny car was dusty now. Tomorrow, Nouri told himself, he'd get up early to clean it. He'd make this car his. Surely, since he'd been A'mmo's favorite nephew, A'mmo would want him to have it.

Nouri wouldn't be able to drive the car for years and years, but he knew it would be waiting.

As they drew closer to Baghdad, the sky ahead burned with the green flash of tracer fire. Explosions rocked the night. Baba drove straight into that war, the one they lived with every day.

As they passed a group of motorcycles stuck behind a horse-drawn cart, Baba patted the steering wheel and said, “We should get a good price for this car.”

Nouri leaned forward to hear better, pushing against his sister, who elbowed him back. How could Baba

suggest

such a thing?

“You'd sell it right away?” Mama lifted her arm, her bracelets jingling.

“Why not? We need the money.”

“It's something to remember Hakim by. . . .” Mama's voice trailed off.

Mama was rightâthe car was all they had left of A'mmo Hakim. “We could use this car,” Nouri said firmly.

Baba shook his head. “Cars cost money to keep. Buses are good enough.”

Nouri leaned back, breathing in his aunt's thick perfume. If only A'mmo Hakim could be alive again, tugging at his smooth white cuffs with the sparkling cuff links. Because of a stupid Sunni, he now lay in a white coffin, dressed in his white suit.

All over Iraqâeven before the American soldiers had arrivedâSunnis and Shiites had been at war. Even though they were all Muslims, they found reasons to hate each other.

Up until now, Nouri hadn't felt any bad feelings toward Sunnis.

Now he thought of Baba's elder brother, who'd married a Sunni. They had a son his ageâhis cousin. Talib was half Sunni, half Shiite, but Nouri had never thought anything of it before. He and Talib had grown up happily together.

But now, when Nouri pictured Talibâhis curly hair and narrow eyesâit seemed like a shadow passed over his cousin's image.

Because of a stupid Sunni, Nouri had had to ride to the cemetery in Najaf City in A'mmo's black car. And now Baba was about to sell that car, the last remains of Nouri's beloved uncle.

ALLAH IS GREAT

With a low, grinding sound, an American tank drove into the neighborhood. It filled the narrow street, scraping against a wall, crushing rocks as it moved. It stopped right in the middle of Talib's war game.

What luck, Talib thought, to have a real tank right here. The American tanks cruised into Karada every now and then, but it had been a while. The tanks traveled slowly and usually never hurt anyone. Talib eyed the dull green metal and the long treaded wheel that moved the tank forward.

“The infidels kill children,” whispered his cousin Nouri, crouching. “They break down doors and kill whole families.”

Talib shaded his eyes and studied the tank again. “But sometimes they give out candy.” He put down his gun and got up. With a chance to get close to an American vehicle of war, how could his cousin act so cowardly?

“But your mother . . .” Nouri glanced toward the house, his straight black hair swinging across his forehead.

Mama worried endlessly about nothing. “She'll be all right. We soldiers do what we have to do.” Talib hopped over the wall and slid into the space between the wall and the tank. Today he felt as tough as the tank itself. He went up to it and banged on the metal side. He called out: “Hello, Mister!”

A few yards down the dusty street, Nouri clustered with their other cousins, Jalal and Anwar. Two years younger, they stood only as high as Nouri's shoulder. The three whispered together.

They always let him be the brave one, Talib thought.

There was no sign of life from the tank. “Hello, Mister!” Talib repeated more loudly. In spite of his bravado, his stomach tightened. Was Nouri right? Every week there were stories of American bombs hitting the wrong target, killing civilians. What were the soldiers inside the tank doing?

Just as Talib took a step back, a soldier poked his head out the small window. He had a round, sunburned face.

Talib waved and the soldier smiled.

“Candy! American candy!” Talib hollered up in English.

The soldier drew his head back inside. A moment later, he lowered a combat helmet down the side of the tank.

Talib stood on tiptoe. He jumped up to see, but the helmet was still too high.