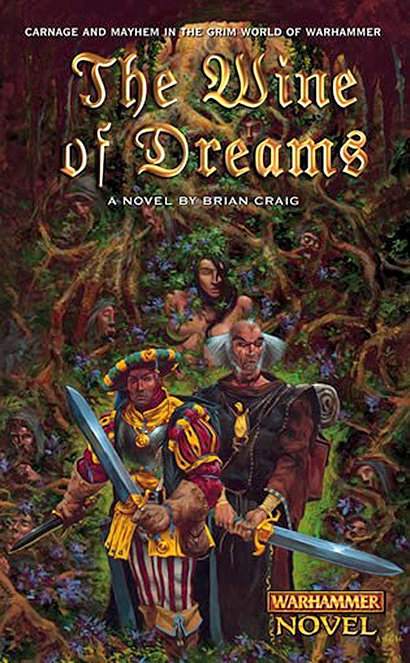

The Wine of Dreams

A WARHAMMER NOVEL

THE WINE OF DREAMS

(An Undead Scan v1.0)

Chapter One

One of the first things Reinmar Wieland had learned after assuming his adult

duties was that the early afternoon was always a quiet time in a wine

merchant’s. Eilhart was a town dominated by convention, and convention dictated

that the housewives of the town did their shopping early, while the milk and

meat were still fresh and the best vegetable produce was still to be found on

the stalls in the market square.

Wine did not, of course, need to be bought while it was fresh. Quite the

contrary, in fact; the very first of the many slogans that his father Gottfried

was attempting to drum into Reinmar’s head held that “good wine matures well”.

Like all the other slogans it was subject to all kinds of exceptions, the value

of an individual flask depending on its source as well as its age, but that did

not prevent Gottfried Wieland from intoning the words as if they were holy writ.

Nor did it inhibit the housewives of Eilhart from shopping for their measures of

Reikish hock at the same time as they shopped for all the day’s goods, in the

early morning.

The consequence of that habit, for Reinmar, was that he had to rise at six

and take his station at the counter before the bell in the tower of the corn

exchange chimed seven. This would not have been so terrible had he been able to bolt the door of the shop when

the market stallholders packed up their goods and trestle tables and set off

home, which they invariably did before four in the afternoon. Unfortunately, the

wine shop always had a second busy period at dusk, when labourers, journeymen

and apprentices would begin to wend their way home from their various kinds of

work. This was the time when all those among them who fared for themselves—the

unwed and widowed who were inconveniently boarded—would provision themselves

for the evening.

Wine was twice as necessary to customers of the second kind as it was to the

members of larger and more careful households, because they had to eat the worst

meat and the most worm-ridden vegetables. A swig of wine between mouthfuls of

food lent great assistance to their palatability.

In the Empire’s great cities, Reinmar’s father had informed him, all manner

of spices were available to disguise the rottenness of poor meat, but such

luxuries were much harder to come by in Eilhart than in Altdorf or Marienburg.

“For which you and I should be profoundly grateful,” Gottfried Wieland had

added, “for it increases demand for our product, and hence its value. You will

doubtless hear other traders wondering aloud why the Wielands have never

attempted to extend the scope of our business further north than Holthusen, but

the towns further down the Schilder are easily reached by the riverboats that

ply their trade along the Reik—and lie, therefore, on the fringe of a much

bigger and much more competitive marketplace. Whenever you hear our own boatmen

cursing the difficulty and tedium of steering barges through the locks between

Eilhart and Holthusen—and you will, when you learn that aspect of the trade—you ought to give thanks, for that is what secures our virtual monopoly of local

business, and keeps at bay the spices that would reduce demand.”

It was, alas, hard for Reinmar to be grateful when the chief effect of this

second wave of daily custom was to delay closing the shop until he was sorely

tired. It was not so bad in the depths of winter, when dusk fell before the

market bell chimed five, but in summer the light lasted for a full

three-quarters of the day and outdoor labourers were kept so hard to their work

that they would still be staggering through the door—invariably carrying a

fearsome thirst—at three hours to midnight.

Reinmar had, of course, suggested to his father that the shop could be closed

for a few hours early on summer afternoons without any noticeable loss of

profit, but Gottfried Wieland was not the kind of man to take such suggestions

well.

“Close the shop!” he had exclaimed, as if the notion were the rankest heresy.

“No noticeable loss of profit! What kind of tradesmen would we be if we were not

available to our customers at any hour at which they cared to call? This is the

Empire, my boy, not Estalia or Tilea. We are civilised folk, and industrious

too. Can you possibly think that life is difficult because you must sometimes

stand at a counter for fifteen hours in a day? What of the folk who toil in the

fields and the forges? What of the men who load and unload the barges, or the

men who go up to the forests to cut wood and burn charcoal? Our life, Reinmar,

is extraordinarily good and easy by comparison with the great majority of men,

and it is honest toil that has made it so. We are not aristocrats, to be sure,

but there is a dignity and purpose in trade which cannot be valued too highly.

Carpenters make chairs, cobblers make boots and tanners make saddles, but

tradesmen make money. There are men abroad in the world who resent tradesmen and

affect to despise them as usurers in disguise, but it is our great fortune to

live in Eilhart, where even the common folk recognise that no finer thing can be

said of any man than:

he makes money.

And of all the wares in which a man

might trade, there is none finer than wine. Cheap wine makes life tolerable to

the poor, and good wine is the best of all the pleasures available to the

comfortably off.”

Gottfried Wieland always emphasised the first word whenever he pronounced the

phrase “good wine”. He was so besotted with his merchandise that he seemed to

consider its finest fraction to be virtue in liquid form. The local constables

and the town magistrate had been known to take a different view of the poorer

fraction favoured by the town’s admittedly tiny criminal element, but their low

opinion did not impress Gottfried in the least. “Drunkards will drink no matter

what,” he would say, waspishly. “Better they should intoxicate themselves with

honest wine than anything worse.”

Reinmar did not know exactly what the words “anything worse” were supposed to

signify, but he knew that the Wieland shops did not stock schnapps, and that

Gottfried always pronounced the words “Bretonnian brandy” as if he were spitting acid. To

Reinmar, Bretonnia was a fabulous place—the substance of travellers’ tales.

Its boundaries lay no more than forty leagues to the south, as the eagle flew,

but one had to be an eagle to get there because the Grey Mountains were

virtually impassable hereabouts; there was no convenient pass nearer than the

Axe Bite, which lay forty leagues to the east.

One day, Reinmar knew, he might go downriver as far as the Schilder’s

confluence with the Reik—but no further than that, if he were content to be a

dutiful son. In the daydreams with which he whiled away the slow afternoons,

however, he often toyed with the notion that once he had gone so far from home

it would be easy enough to take a westbound boat to Marienburg or an eastbound

one to Altdorf. Perhaps he would never see Bretonnia, but he would see

civilisation at its finest: a world in which a free man might make the most of

his freedom.

In his daydreams, Reinmar longed to be free. In his daydreams, he yearned for

a better world than one in which achievement was measured in honest toil and

virtue in good wine.

The hope of one day being able to defy his father’s sterner advice was what

carried Reinmar through every lonely hour that he had to spend standing by a

counter in an empty shop, and that hope increased with every year that went by

as his fourteenth, fifteenth and sixteenth birthdays passed. As he grew older,

his duties were further extended, and so was the intensity of his frustration.

“It’s always the way,” his grandfather would say, when he took leave to

complain. Even his grandfather, who seemed to be perpetually at odds with

Reinmar’s father, had become grudging with his sympathy of late—but he was an

old and sick man, who regularly demanded far more sympathy than he was prepared

to offer. Reinmar’s nearest neighbour and closest childhood friend. Marguerite,

was infinitely more generous but had lately become far less imaginative.

“But it is always the way,” she told him. “That’s what life is like.”

Reinmar’s seventeenth year was the first in which manning the shop had become

a full-time occupation with no allowance for any part of his education. Even his

training in the arts of self-defence, which he had always enjoyed, was now considered to be complete.

From now on, if Gottfried Wieland had his way, Reinmar’s work would be Reinmar’s

life. Sometimes he wondered whether he might not do better to take his skills to

the city and become a soldier in the Reiksguard. Reinmar had, of course, always

known that the family business would become his work, but while he still had

opportunities to play he had not anticipated the crushing weight with which

responsibility now seemed to bear down upon him. As the days of his seventeenth

year lengthened from winter to spring and from spring to summer the shop was

transformed in his imagination into his prison, and he began to fear that once

he was fully committed to it he would never be released.

Apart from his daydreams, however, there was one prospect to which he could

look forward and whose anticipation saved him from despair. When the crops had

ripened in the summer sun and the harvest was gathered in he would go up into

the hills with Godrich, his father’s steward, taking sole responsibility for the

very first time for the purchase of this year’s vintages.

The time soon came when he began to count down the days to this expedition,

and the countdown in question inevitably came to seem exceedingly slow, but

Reinmar could not help thinking of it as the countdown to a moment of decision:

the moment when he would have to settle his own mind once and for all as to

whether he would accept the life that his father had designed for him, or

whether he would hazard everything in following one or other of his speculative

dreams.

He always assumed, as he mulled this matter over, that the choice was his

alone and that it would be freely made—but he had known no life other than the

everyday life of the townsfolk of Eilhart, and he had innocently taken it for

granted that a life of that kind was an unchanging and unchangeable ritual, safe

from all disruption.

That assumption was, of course, quite false.

The afternoon on which Reinmar’s countdown reached single figures for the

first time was a particularly vexatious one. The weather was exceedingly warm

and sultry, and the atmosphere in the shop seemed as thick as soup. The morning

rush had ended early because the town’s housewives had not wanted to linger too

long outside on such a day.

To make matters worse, Reinmar had offended Marguerite two days before. He

had charged her with “pestering him with trivia”, and he knew from long

experience that unless some powerful motive intervened she would avoid him for

at least three days. Although he and Marguerite had been the best of friends

since the beginning of his memory, Reinmar was far from certain that he wanted

their friendship to develop further in the way that everyone—not least

Marguerite—seemed to expect. She was a pretty girl, after her bland and blonde

fashion, but not as pretty as the dark girls with exotic eyes that Reinmar often

saw in the square on market days, selling metal trinkets and medicinal charms.

While Marguerite stayed away, though, there was no relief from boredom

available to Reinmar but daydreaming, and even his daydreams seemed to have

grown stale from recent overuse. The comfort that he usually found in fantasies

of flight and adventure was not to be found on that particular day, and in the

absence of that comfort he had grown irritable and desperate. By the time the

customer came into the empty shop, when Reinmar should have been glad for any

distraction, his mood was too bad to be lightened by anything so slight.

Had the customer seemed more interesting in himself, Reinmar might have been

able to rouse himself from his ill humour, but the only interesting thing about

the man, at first glance, was that he was a stranger. Reinmar had plenty of time

to study him while he prowled the racks, peering at the goods on offer. He was

short—hardly half a hand’s-breadth taller than Reinmar—and somewhat stout.

His hair was dark, but not uniformly black, and there was two days’ growth of

black beard staining his jowls. The quality of his clothes suggested that he was

more likely to have arrived in Eilhart by barge than in a carriage, although he

was not costumed as a stevedore. His hands did not seem to be marked by habitual

use of ropes or tools, nor did his face have the leathery appearance given by

long exposure to the sun, but he certainly did not have the look of a gentleman.

Reinmar was not good at guessing any man’s age, but this one posed a

particular puzzle; he might have been anywhere between thirty and sixty. His

eyes were narrow, dark brown in colour but startlingly bright whenever they

caught the shafts of sunlight that filtered through the narrow windows.